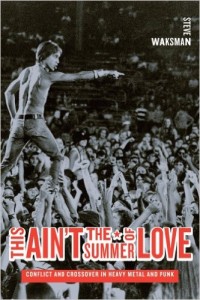

Waksman, Steve. This Ain’t the Summer of Love: Conflict and Crossover in Heavy Metal and Punk. Berkeley: California UP, 2011.

Waksman, Steve. This Ain’t the Summer of Love: Conflict and Crossover in Heavy Metal and Punk. Berkeley: California UP, 2011.

In one of my favorite Nathaniel Hawthorne sketches, “Dr. Heidegger’s Experiment,” the eponymous doctor invites four aged friends to taste a water he claims will restore their youth. After demonstrating the effect on a half-century-old rose, Heidegger expresses the (sardonic?) hope that, in their second youth, his friends would become models of virtue rather than succumbing again to dissipation. Of course, his guests assure him, clamoring for a drink. The effect of the water is immediate: all four are rejuvenated, and end up parading around the room, admiring themselves in the mirror and ridiculing their former infirmity. Heidegger himself only watches. His friends’ behavior under the “delirium” of the elixir is enough to convince him that its magical properties are not for him. He is a different kind of mirror, a moral one, as so many a Hawthorne character and narrator is. Nor is the actual mirror in Heidegger’s study devoid of said quality. As the three men vie for the attention of the newly “girl widow,” “by a strange deception, owing to the duskiness of the chamber, and the antique dresses which they still wore, the tall mirror is said to have [!] reflected the figures of the three old, gray, withered grand-sires, ridiculously contending for the skinny ugliness of a shriveled grand-dam.” Just in case the reader was looking for stable footing, the narrator claims that he himself “bears the stigma of a fiction-monger.” And so—again, typical for Hawthorne—there is a delicious, crepuscular ambiguity as to whether the transformation is real, or Heidegger is watching four old fools captive of a delusion.

I thought of Hawthorne’s sketch more than once while I was reading Steve Waksman’s excellent revisionist heavy-rock history This Ain’t the Summer of Love. In Greil Marcus’s classic formulation, the arrival of punk onto the scene in ‘76 was a “pop explosion”: “a moment of anxiety and rupture that created […] a stark sense of ‘before’ and ‘after’”; the “historical slate” had been “wiped clean” (Waksman 148, 149). And yet, as Waksman shows, for “a small but vocal minority” of rock journalists, spurred by “a mix of nostalgia, narcissism, resentment, and rebellion” (65), the “explosion” of ’76 was not really an irruption of the New; it was the Second Coming. For ’76 simply fulfilled the promise of Nuggets, Lenny Kaye’s legendary 1972 compilation of mid-‘60s garage rock, that last last great moment in rock ‘n’ roll history, whose youthful energy had been dissipated by the anathema of prog-rock pretentiousness and the tuned-in, introspective listening of the audiences for psychedelia (see Waksman 30).* Nuggets, Waksman writes, “embodied the search for a way to channel the most unleashed qualities of rock in new aesthetic directions and the desire to counteract the growing hierarchies—economic and artistic—that had developed around the music during the past half-decade” (66). Despite the emphasis on the “new” here, Waksman is quite clear that Nuggets was first and foremost an act of nostalgic reclamation (69). I can’t help but see them—Lester Bangs, Greg Shaw, Lenny Kaye et al.—standing around with their fingers crossed, haranguing passers-by with their vinyl pamphlets, like Jehovah’s Witnesses on the subway platform. Never mind the messiah, here’s the Sex Pistols.

There is something deeply romantic about this vision,§ and Waksman is not slow to point it out. Shaw, a self-proclaimed “rock purist” (50), believed that by the early ‘70s rock had “lost the ability to represent youthful desires in […] a direct way” (52-3; my emphasis); and it was by this lizard brain-to-neocortex ratio that the worth of all rock was to be measured. Ideally, the denominator must approach zero, and so the ratio infinity, until the audience brushed up against the asymptote of a Maenadic orgy of self-annihilation. To live suspended between two utopias, watching, waiting for the next artist who would “save” rock ‘n’ roll—by which we can only mean ourselves from the consciousness of our own aging and imminent death—strikes me as simply the Heideggerian impulse writ large. Indeed, it is the very warp and woof of post-‘60s America.

I think it was Jello Biafra who said he hated punk nostalgia. How ironic, then, that punk should turn out to be all nostalgia; that the answer to the perennial question “How to keep rock young?” (Waksman 145) should be through periodic injections of the past. Of course, this is as much a polemical exaggeration as Shaw’s: the “new aesthetic directions” are as important as the spirit of rock revived. I will return to this later. For the moment, suffice to say that punk as “pop explosion” is a hyperbole of wish-fulfillment. The story is clearly more complicated than razing history by cultivating the barbaric yawp of hormone-addled teens, and Waksman’s task is to tell this more complicated story. How is it that this odd beast called Heavy Metal, hardly the tiny mammals of the paleontological imagination, survived that icon-shaped meteor called Punk? Why did Metal, as The Dude would say, abide?

*

The mythology of punk had to be constructed against something, and that something would be metal, wayward child of prog and the blues, the dark twin from which punk was separated at birth. Indeed, the labels—punk, metal—are historically so fractious that we’ve forgotten the days when Bangs et al. were singing the praises of early Grand Funk (and even Black Sabbath) for carrying something of the “squalid” (66) garage-rock aesthetic into the era of the stadium, and when GFR could be lumped together with MC5 and The Stooges around ideas of spontaneity, unleashed desire, and populism (67). This Ain’t the Summer of Love is a fine remedy for the cultural amnesia that has hampered our understanding of these two genres’ tangled histories.

“Metal and punk,” Waksman writes in his introduction, “have enjoyed a particularly charged, at times even intimate sort of relationship that has informed the two genres in terms of sound, image, and discourse” (7). Rather than a fixed boundary between them, he posits a “continuum,” through which “generic boundaries have been continually tested, sometimes to be remapped and other times to be reinforced” (10). Waksman is interested in re-telling the story in such a way that punk and metal mutually illuminate each other, and to highlight not just tensions and antitheses, but the reciprocity and cross-pollination of their imbricated evolutions. By redefining the relationship between overtheorized (to the point of fetish) punk, and the until recently (and perhaps still) undertheorized heavy metal, the study spurs us to “question some of the assumptions that have led to the canonization of punk as the last great moment in rock history” (17) … and as such, to hear rock history differently.

Waksman might quibble with me here (and there, and everywhere), but This Ain’t the Summer of Love strikes me as deconstructive in spirit.† By unearthing the nostalgic wish-fulfillment that impelled the “canonization of punk” as the antithesis of “dinosaur rock,” Waksman dismantles a critical binary by which the two genres have often been distinguished. The goal here is neither to invert the hierarchy (metal rules!) nor to eradicate distinctions (metal IS punk), but rather to reveal the role of ideology—where metal simply becomes the foil against which to shore up punk’s authenticity, the scapegoat onto which punk can cast anything it cannot countenance in itself, the representative of the worst excesses to which the spirit of rock can be degraded, in order for punk to believe its myths about itself—in the way the two genres are understood and understand themselves, as well as to map how each genre has impacted the other in that “charged, intimate relationship.”

For example: the desire for mass success has generally sat better with heavy metal than with punk, which repudiated the machine of rock stardom. In this formulation, heavy metal comes to represent the capitalist means of production of the “rock-industrial complex” (stadium show, major label, etc.), punk the conscious, liberated masses (however un-massed they might be) existing in authentic relation to the band. And yet, early punk bands found it difficult to spurn the crowd or the major labels when they came knocking. Were said bands therefore un-punked, “sellouts,” their authenticity just another pose? Writes Waksman about the uncategorizable Dictators: they “thumbed their noses at the terms of rock-and-roll success but still continued to struggle mightily for it” (127). It is a comment that could be applied more broadly.

Of course, binaries are like rabbits, or characters in the Pentateuch: one is continuously begetting another. Slow versus fast, pretentious/arty versus gonad-driven, spectacular versus intimate, passive versus active, hierarchical versus democratic, centralized versus decentralized, amateur versus virtuouso, etc. … I will not presume to identify the pater-binary here. While it is true that differences in musical practice and production are expressions of differing ideologies, the genre labels have the effect of exaggerating them, erecting artificial barriers along the “continuum,” distorting how we hear the music, and deafening us to points of merger and cross-influence.

I would take this one step further and argue that, from the perspective of heavy metal, music and ideology form a binary of their own. That is, metal would like to believe it has no ideology, would understand itself as a purely aesthetic phenomenon, with music and musical practice at the center of the subculture. This makes sense, given its historical love-hate relationship with the mainstream. Punk, on the other hand, was always conscious of its ideology, or of itself as ideology. The music was of a piece with it, but was never understood as an entity separate from it. For punk, the music was a sort of caulk to hold the subculture together, present in every nook and cranny, but not itself the scene. The opposite is true of metal: the music is the scene; the metalheads fit themselves into those cracks, bearing up the music together. Music creates solidarity in metal, rather than being one (perhaps the highest) expression of it. (According to this formulation, no matter how punk-influenced metal has been, the answer to the question, “Is there metal beyond metal?” which was posed at the 2013 Heavy Metal and Popular Culture conference (see “T-Shirts and Wittgenstein,” 5.24.13) must be “No.”)

Perhaps, if punk is more a creature of ideology than of its aesthetic expression (e.g., anti-virtuosity and -complexity), it is as much in need of metal to give it musical life as metal needs that other thing punk has from time to time given it: attitude; energy; the dismantling spirit of noise and a dissonance edging into atonality (and anarchy) that visits rock whenever it becomes too enamored of its own edifices. Without metal, punk burns itself out; without punk, metal ossifies. Again, since metal pretends it is not ideological, it is happy to draw on punk for inspiration, including musical inspiration; whereas for punk to do the same can only appear a betrayal, since one cannot delve into metal without dragging the whole kit-and-caboodle of its (reactionary, hierarchical) ideology behind.

If we look to the New Wave of British Heavy Metal (NWOBHM) era, we are left with the fascinating and troubling suggestion that metal became metal via punk, found its voice because of punk. (It reminds me of the scene in Invisible Man where the protagonist makes white paint by stirring black paint into it …) Here, metal becomes metal not via the mirror of its Other, but by incorporation—that is, because of a certain level of “impurity.” So, just as there was no pure rock in some past utopia that we can remake in the present, so there is no pure or true genre; it is essentially contaminated, always in the process of making itself, cobbling itself together from the bric-a-brac of the musical past, subject to the forces of media and market. Its achievement is aspirational, and endlessly deferred. Ah, these quixotic attempts to redeem the sinner and refine the defiled! The “purity virus,” as we might call it, can be quite as debilitating as what Bangs called the “superstar virus” (Waksman 54). Now, in “taking in” punk, was metal paradoxically infected by the purity virus—the very same virus that leads punk to define itself against metal as ur-representative of the musical past? Perhaps. But it may have been just enough to inoculate it: to create a firm yet still-porous membrane that would allow both a relatively stable generic identity and the possibility of change … and thus the preposterous longevity which has so flummoxed its detractors. Perhaps punk was necessary to show metal that it does have an ideology, and so to help it come to consciousness of itself as a genre.

And punk? Since punk is the privileged term, it has the privilege of pretending to be sufficient unto itself: punk is punk is punk. Or: punk is pure negation, an anti-genre, nothing without the contours of the generic history it mythologizes itself razing to the ground, an energy that “infects” other genres, and that is the essence of its paradoxical purity. Or: punk is … punk is …. After a time, defining punk comes to seem as elusive as locating the proverbial True Scotsman. Punk, the fleeting utopia (was it actually ever there?), the grail-shaped elementary particle created in fiery collision, decaying at the instant of its detection.

*

There is a danger here, no matter how fine a blade one uses, of treating the genres monolithically, of re-stabilizing the very generic binary Waksman would have us think about fluidly, historically. (Notice how much of the above is written in the present tense.) All this talk about binaries is making me hungry … for history, that is. And since the above admittedly weaves far away from Waksman’s study, which is so firmly grounded, it is high time we re-grounded ourselves in the text.

Perhaps something of the foregoing discussion can help reveal why metal’s place throughout the book feels a little problematic. The idea that punk was a sort of reservoir from which metal could draw energy, “revitalizing” it during periods when it was flagging, and pushing it in ever-more-extreme directions, makes metal the dependent genre. Only when metal had developed “an underground energy of its own” (239) would the current be freed to flow in the opposite direction, helping to release hardcore from the mirror of its fetishized purity, polluting it with the dungheap sounds of Black Sabbath, Ted Nugent, and AC/DC, and producing first crossover as a self-consciously hybrid genre (D.R.I., Suicidal Tendencies, C.O.C., S.O.D.), and eventually the more thoroughly-digested hybridity of grunge. Then again, perhaps the feeling of imbalance is an inevitable product of the way rock history has been written; the Standard Model always exerts a gravity on any counternarrative, be it about minority populations or minority musics.

Regardless, the history Waksman tells is compelling: nuanced in argument, deeply researched, and smartly contextualized by cultural changes in twentieth-century Britain and America, from suburban male tinkering to the changing meaning of postwar youth culture. Not surprisingly for a book about “crossover and conflict” between countergenres,** chapters are dominated by pairs—GFR and Nuggets, Alice Cooper and Iggy Pop, The Runaways and The Dictators, Iron Maiden and Def Leppard. “Death Trip,” the Cooper-Pop chapter, is particularly insightful about these two figures who stood at the headwaters of the generic division that would emerge over the ‘70s, initiating both aforementioned founding differences (e.g., large-scale spectacle versus intimacy and authenticity) and shared fixations (victimization, death, gender ambiguity). In the third and fourth chapters, Waksman turns his attention to early attempts at crossover. Some of the most interesting material examines the way ‘70s bands’ hybrid identities and competing agendas made them unstable. For The Runaways, for example, the tension between Joan Jett (punk) and Lita Ford (metal) tore the band apart. A few years later, Iron Maiden would more successfully navigate a similar tension by ejecting the offending matter—original singer Paul D’ianno, whose voice, stance, and look screamed punk—and consolidating their image around the operatic Bruce Dickinson (201). With D’ianno, Maiden had been touted as a crossover band; even the original Eddie, the band’s endlessly-mutable mascot, clearly bore the marks of both genres (see 196).

What happened between The Runaways and Maiden that allowed the latter to enjoy at least a few pre-thrash years straddling the two genres? One word: Motörhead. Only peerless Motörhead, mother of all crossovers, get their own chapter. They were noisier and dirtier and less bassy than other metal bands, albeit proficient enough instrumentally; in Waksman’s lovely phrase, “their music was all distorted rushing surface” (165). Both punk and metal writers in Britain claimed Motörhead as their own, whether as the fulfillment of the sound Johnny Rotten prophesied, or as stripped-down heavy rock without a political agenda and a biker look to boot (160-1). Audiences for Motörhead were motley assemblages of punks and metalheads, a phenomenon that would continue with Maiden and the NWOBHM. For Sounds writer Geoff Barton, for example, a 1979 concert of NWOBHM bands featuring Maiden “showed that punks were not so ready to leave the musical past behind as they were often portrayed, and that heavy metal retained a vital degree of currency amid the social divisions that defined the British music scene” (177; the words are Waksman’s).

Punk’s impact on metal would become increasingly transparent—and oft cited, though not without occasionally disparaging comments on punk musicianship (166)—as the ‘70s drew to a close, penetrating to all levels of musical activity: independent labels, local scenes (even if these were meant as stepping stones to stardom rather than ends in themselves), and more extreme styles. It was NWOBHM bands like Raven and Venom who would push the quest for a new, metal-specific authenticity the furthest—that first injection of “punk attitude,” as both D’ianno and Venom’s Abaddon put it (195, 199)—and so have the biggest impact on the rise of the ‘80s metal underground. Mixing a noisy, DIY sound with metal themes, Venom claimed to prefer a punk label to being classed with “unworthy” heavy metal bands (194). In their marginalization from the heavy metal mainstream, they became the genre’s “ultimate purveyors” (195), using punk to scour away any and all extravagances, and redefining the fringe as the new center.§§ A couple of years later, as the meaning of the New Wave shifted, so did the NWOBHM, toward a pop-friendlier sound of short, tight songs with catchy leads (e.g., Def Leppard). Thus, as the different sounds, fates, and degrees of influence of Motörhead, Maiden, Venom, and Leppard show, the impact of punk on metal in late ‘70s/ early ‘80s Britain is ambivalent, even contradictory. While it is true that NWOBHM was an attempt to “come to terms with the impact of punk,” “metal bands of the time were as likely to be reacting against punk as incorporating its values and features, and may have been doing both at the same time” (209).

This true-versus-mainstream divide arising from British metal’s uneasy late ‘70s/early ‘80s interaction with punk would soon take on a decidedly Atlantic cast, with the distinctly un-punk and orthographically-challenged Leppard pandering to American audiences, the same audiences who would soon be buttering the bread of SoCal proto-hair bands like Quiet Riot and Mötley Crüe.†† Meanwhile, independent American labels were beginning to foster stateside underground scenes, helping to pave the way for American crossover. SST, founded by Black Flag guitarist Greg Ginn, grew away from hardcore dogma so that, by the mid-‘80s, their catalog was offering a mix of punk and metal—including Black Flag’s own divisively metal-inflected My War (1982). For Waksman, SST helped “legitimate the inclusion of heavy metal in the independent realm” (228), even as he notes that metal was already creating its own version of DIY culture via its European connections (the Danish fanzine Aardschok, for example, and the NWOBHM). With the emergence of originating thrash metal bands like Slayer and Metallica further up the coast, hardcore ‘zines began to sit up and take notice; some began to call for détente between and even unity among the two scenes.*** Independent Metal Blade would go on to record crossover pioneers D.R.I. and C.O.C. Eventually, the “Seattle Sound” would be built from the bricks and mortar of these crossover tendencies, fused by the isolated and closely-knit musical culture of that city. For Waksman, SST and Metal Blade each had a role in fostering crossover, but only Seattle’s Sub Pop “made the combination of metal and punk into the basis for a broad-based youth culture that reshaped the rock music industry in the first half of the 1990s” (254); it was “the one genuinely mass-oriented music phenomenon […] predicated on the interplay between heavy metal and punk” (301).

This Ain’t the Summer of Love ends like a classic novel: in marriage (with children!). But did the couple live happily ever after? The outcry over Metallica’s headlining Lalapalooza, five years after they went “alternative,” suggests that grunge was only a partial, or momentary, resolution. Waksman’s reading of the evolution of Lalapalooza is brilliantly on-target: “It was almost as though the 1960s-70s shift from festival rock to arena rock was being replayed all over again in the context of a single annual event” (304). By beginning at the dawn of the ’70s and concluding with the Blue Öyster Cult song from which the book takes its title, Waksman suggests that, to truly understand the evolution of punk and metal, one has to go back to that very shift, to the genres’ dual emergence on the other side of the Altamont faultline. BOC’s “This Ain’t the Summer of Love” is a postmortem for “the pastoral, communitarian mythos that surrounded [rock ‘n’ roll] at a particular point in time […] 1970s rock is not about going back to the garden, it’s about riding into the night noisily and with abandon” (297).

As Waksman shows, there are different kinds of gardens; garages will do quite as well for flowers as Golden Gate Park. But the anti-nostalgic impulse carries a danger as well: the fantasy that history can be scraped off of the present, and time begin anew. (Indeed, the anti-nostalgic impulse may be just cloaked nostalgia.) If punk and metal were “efforts to reinvest rock with meaning after the perceived demise of the 1960s counterculture” (18), then what meaning(s)? To what extent revived, imported, contemporary? The central question of the book may be not about the mutual influences between musical genres, but about how to engage with the past without succumbing to either nostalgia or resentment; or without, as James Baldwin once wrote, either drowning in it or replacing it with a fantasy.

*

Some twenty years later, where are we? Sometimes I wonder if, for people of my generation, the genres are as polarized as they ever were. Waksman’s personal story, which he glosses in his introduction, is familiar to anyone who grew up in the ‘80s and invested him or herself in either or both of these genres. He identified as a metalhead; his heavy metal T-shirt marked him as “other” in that epicenter of hardcore, Orange County. But he listened to some punk, and, after his punk college roommie discovered him spinning a Black Flag record, he started going to shows. I grew up three thousand miles away, but everything about Waksman’s narrative resonates with me. We grew from Led Zeppelin and Rush toward something starker, darker, heavier, filtered into punk or metal depending on a variety of social and cultural circumstances. I had metalhead friends who drew a more or less firm line between metal and punk, and others who tried to find their own positions between the two, and even among Brit-lithium bands like The Smiths and The Cure. One, a diehard Metallica fan, floated me my first hardcore: early Tendencies, D.I., and Blag Flag’s Family Man. Another, a one-time skinhead, later became an enormous influence on my taste, seeding me with Beefeater and SNFU while I did the same to him with Voivod: places where divided currents rejoined. We all have stories like these, friends like these: holes poked in the seemingly impregnable walls of genre, notes and cigarettes passed between, smoke blown through, this no matter how wedded we were to our perfectly masturbatory musical identities.

Today, I find that those who held a firm genre line tend to be nostalgic for a certain tribalism, before everything got thrown in the hopper and blended up—before, say, a band with a violin could be called metal, and kids in Brooklyn listened to country. Waksman’s point about grunge’s tangled genealogy, its deep hybridity, is borne out by the way these hard-line friends hear it, whether they subscribed to the metal or punk-cum-indie rock side of the line. Kurt Cobain, for example, is contested terrain. He is generally understood as a punk hero by indie rockers, and the antithesis (one even sees this in Waksman) of grunge’s other multiplatinum success story, Pearl Jam. My nostalgically metalhead friends (you know, the ones who think music died with the ‘80s, was briefly resurrected in Pantera, and then died for real) also have a hard time swallowing Pearl Jam … but some of them claim Nirvana for metal. Alice in Chains has always gone down a lot easier, and even Soundgarden, despite their propensity for parodying metal. But the reticence about miscegenation runs deep as identity. On my end, I love Pearl Jam—I hear not just ‘70s rock, but punk, The Beatles, and much more—and never developed much of a taste for Nirvana. Then again, listening to my iPod on shuffle in the car, I find myself increasingly skeptical of the old allegiances. The music jumps from Queensryche’s Operation: Mindcrime to Slayer’s South of Heaven, both from ‘88. To what extent was it ever possible to understand these bands as belonging to the same all-encompassing parent genre? My beef is not with evolution per se, of course. I just sometimes marvel at the arrangement of the phyla, always a conventional frame laid over what is indeed a continuum, and—at least where the consumption of music is concerned—usually done so by forces outside of our control.

And the “kids” today, where are they at? Barring statistics about tastes and attitudes, the only evidence (once again) is anecdotal. And what anecdotal evidence I can muster is ambiguous, even contradictory. On the one hand, the taste of younger crowds seems to run the gamut—“genre be damned!” seems to be the rallying cry today—and bands post-grunge happily draw on both “energies.” Cobain himself has acquired the same legendary, common-property status that Jimi or Joplin have; he seems to be the only such figure that has currency among today’s youth audience for rock (which is also why he is contested terrain). In the local music ‘zines where I live, the same publications appeal to both metal and hardcore fans, although there is still a good deal of attention paid to which aesthetic a new local band more or less subscribes. On the other hand, genre has splintered to such a degree that micro-identities seem to isolate audiences within not just genres, but subgenres. If the resulting constellations are not always predictable and channel-able as they once were, they can be just as fiercely guarded. “Crossover” bills may make money, but perhaps only because they gather enough people from different audiences and scenes, not because the audiences themselves cross over … even if the Cro-mags fans aren’t kicking the shit out of the Slayer fans anymore (I wonder if this was the case back in ’79 in Britain as well). Add to this the retro- aspect of today’s audiences, with neo-punks and neo-metalheads digging deep into ancient catalogs, and constructing identities from the bones of their forefathers, and one begins to wonder if that nostalgia for tribalism, be it around punk or metal, propagated by music media, has been absorbed by the youth of today as a way of shoring up their own identities against the endless stream of available music. Or perhaps it is simply natural for youth to crave the sort of ready-made identity that popular music provides.

From the standpoint of contemporary politics, there is a (for me) happy payoff to Waksman’s study. For one of the great values of This Ain’t the Summer of Love is that it so well demonstrates the contingency of the border between the two genres and scenes. For the most part—and I will focus on America here—the suburban youth who patronized hardcore were as alienated from the traditional working class as they desired to be from the plastic world of their parents; the proletariat remained theoretical. Meantime, the working class was listening to arena rock/ metal; their politics were reactionary and populist. (Surely a large number of suburban youth also populated that audience, and became much of the audience for ‘80s underground metal: one that aped the working class, as Deena Weinstein showed … but was devoid of both working-class roots or a revolutionary ideology.) Between a working class that embraces capitalism aspirationally, and which finds its greatest exponent in the Horatio Alger rock star, and a disaffected suburban youth without any authentic connection to that working class, who scowl and sneer at “the system,” but are entirely impotent to effect change: “punk” and “metal,” labels that help drive the ideological wedge between the middle and working classes, pitting them against each other for the benefit of the 1%.

But to return to aesthetics, and to my beloved monoliths. Punk and metal have always needed each other to check each other’s worst excesses; they are perhaps best construed as warning labels: stay away from idealized poles, where ideology is mistaken for life. What else could have saved hardcore from drowning in the mirror of its own purity, or from the delusion that it was the vanguard of the apocalypse? And what could have saved the lumbering, masturbating spectacle of metal from itself, if not the noisy anti-energy of punk? Each of us might put our fulcrum in a different place along Waksman’s “continuum,” but some Cygnus there must be. There must be a similar balance, I think, about the way one approaches the past—between, that is, nostalgic romanticization and anti-nostalgic rebellion; between death by drowning and a life of fantasy. For Waksman, the success of grunge seems to have been its ability to negotiate both generic and generational pitfalls: “resources from the past became the means to counter the orthodoxies of the present and to create a new synthesis that melded hardcore’s radical sense of refusal with the ambivalent embrace of heavy metal excess” (298). For the artist of today, weaned on notions of the anxiety of influence and in a culture that is at once hyper-aware of the immediate past and with the technological means at its disposal to both endlessly confront and endlessly recycle it, negotiating the opposing pitfalls of nostalgia and rebellion seems the essence of the creative struggle.

*

Oh, dear. This is a ramshackle house of a “review.” Some very nice individual rooms, you will agree: so pleasantly decorated, the grillework so fastidiously done over, the wallpaper fascinatingly intricate, and mirrors, my God, mirrors everywhere, making everything appear larger than it is. But it is true that, viewed from a distance, it is a bit of a monstrosity: an amalgamation of strange, misshapen additions, as though there had never been a hearth. I won’t even tell you about the rooms left on the drawing board; the Alice Cooper-Iggy Pop one was particularly beautiful; perhaps they will become future additions, or better yet, outbuildings. For now I am running—running, abandoning the place, before I have the urge to grab my tools again, and build yet more rooms, and renovate old ones … and even to re-decorate rooms that will later fall to the sledgehammer! When I have reached a minimum safe distance in time, the great gravity of this house only enough to make my teeth sing, and my pen has turned into a pillar of salt, then, then I can begin to dream of returning.

* Perhaps even nostalgia about nostalgia, a Third Coming. In his third chapter, “The Teenage Rock ‘n’ Roll Ideal,” Waksman takes us even further back, to the lost teen utopia of the 1950s: America’s Garden of Eden, the competing figures of Gidget and The Wild One, the beach kid and the juvenile delinquent (111-112). America, Christopher Hitchens once noted, seems to have a talent for misplacing its innocence. Anyway, among the many strengths of Waksman’s book is its close attention to the pivotal role media—journalism, radio stations, record labels, and anthology recordings—play in shaping musical genres, and by extension music history.

§ Bangs may masquerade as a cynic, but … what a gloriously seductive costume. I can’t think of a rock writer I read with more pleasure. I am generally too happy getting lost in the whorls of his language to bother stepping back to disagree. N.B.: Bangs, for one, recognized the tension between what he called “The Party” and self-consciousness (see Waksman 56), and tried to solve it in typical Bangsian fashion, that is, by recourse to his methamphetamine style.

† Deconstruction itself has become (must become) an object of nostalgia. It does seem oddly apt to use an intellectual tool that came to prominence in the ‘70s and ‘80s to discuss changes in music in the ‘70s and ‘80s. To each time, its tool. That said, I am not sure why intellectual tools should fall out of use. If I am trying to pull nails out of the floor (of culture, in this case), a claw hammer is going to serve me as well as anything since invented, and perhaps better than anything yet invented. Interpretative frameworks—generally cobbled together from different disciplines, grafted with varying degrees of success—are as maniacally sought after, and just as prone to obsolescence, as any other commodity … and therefore, as much a product of the ideology they are ostensibly used to critique, no? Anyway, a new area for eBay to exploit.

** The term is Heather Dubrow’s; I might have done well to raise it earlier. Countergenres are genres that “work according to a set of norms that are implicitly or explicitly drawn from and at times opposed to each other” (Waksman 9). Waksman notes that relationships between genres and the transformation of genres are undertheorized.

§§ Waksman draws on the concepts of mundane and transgressive subcultural capital to analyze Venom’s role (184-5). For a fuller discussion of these concepts, see Keith Kahn-Harris, “‘You Are From Israel and that is Enough to Hate You Forever’: Racism, Globalization and Play Within the Global Extreme Metal Scene,” in Metal Rules the Globe (Duke UP, 2011); and my own discussion of Kahn-Harris’s argument in “T-Shirts and Wittgenstein” (5.24.13).

†† One of my favorite anecdotes in Waksman’s book tells of Def Leppard’s Joe Eliott stripping off the union jack to reveal the stars and stripes. The equation of authentic or true heavy metal with Britain is nowhere better stated than by Rob Halford a few years later: “The USA still looks to Britain as the true origin of Metal […] I honestly don’t think that there has ever been a true American Heavy Metal band!” (333). Judas Priest, as Robert Walser once noted, aspires to be genre-defining. For the irregular ways in which claims to authenticity intersect with masculinity and social class, as well as with nationality, see pages 201-206 in the Waksman.

*** A shout-out to Pushead (Brian Schroeder), who wrote so passionately about punk-metal crossover for Maximum Rock ‘n’ Roll: “Now the crossover has happened and the 2 underground energies are colliding. This is speedcore. There is still hardcore and metal, but in a general sense, the ferocity and quickness brings a unity for those who enjoy it” (239). Today, Pushead is best known for the artwork he produced for Metallica. He should also be remembered—fondly? disturbedly?—for fronting over-the-top speedcore band Septic Death.