If hindsight is 20/20, then Vio-lence was the greatest thrash metal band, period: the band in which the subgenre climaxed, and in particular the Bay Area sound that was its epicenter and still, I think, its purest expression. They were the meridian of the subgenre’s day, to put it in the terms of Judge Holden from Blood Meridian, whose discourses should be compiled into a pamphlet titled How to Listen to Heavy Metal. San Andres be damned: it was that northern tribe, the Cascadians, who would shake the thrashers into the sea. Would that those San Franners had built grunge-resistant edifices …

If hindsight is 20/20, then Vio-lence was the greatest thrash metal band, period: the band in which the subgenre climaxed, and in particular the Bay Area sound that was its epicenter and still, I think, its purest expression. They were the meridian of the subgenre’s day, to put it in the terms of Judge Holden from Blood Meridian, whose discourses should be compiled into a pamphlet titled How to Listen to Heavy Metal. San Andres be damned: it was that northern tribe, the Cascadians, who would shake the thrashers into the sea. Would that those San Franners had built grunge-resistant edifices …

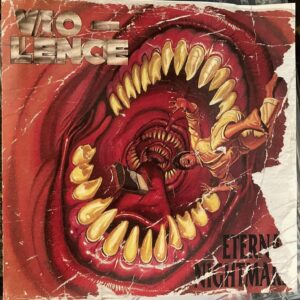

Today, on their Facebook page, fans call Vio-lence “criminally underrated” and “virtually unknown.” I suppose that, compared to Machinehead, the band guitarists Rob Flynn and Phil Demmel went on to found after the scene crumbled, that is true. But they forget, or perhaps never knew, these whippersnappers, the hype that surrounded Eternal Nightmare, Vio-lence’s maiden effort, when it was released in ‘88. I remember at least one genre ‘zine balking at the hoopla, claiming band and album were overrated. Be that as it may, Vio-lence quickly jumped onto a tour opening for Voivod and Testament; and when Voivod had to withdraw due to Piggy’s illness, they moved up to the second slot; at L’amours at least, Blood Feast filled in as openers. With the release of their second album, 1990’s Oppressing the Masses, the band found themselves headlining the national club circuit. I caught them at Baltimore’s Network. The date was mis-advertised; there was almost nobody there.

I explained this to Demmel after the show; I remember him claiming that the band had been outdrawing Voivod on that tour. I guess this was important to him, and is maybe part of the reason, aesthetic ones aside, he and Flynn moved on to bigger things. As did our conversation: we talked about the awesomeness of the guitar leads on Masses, which, like a true gentleman, and in a comment that reminded me of something Glenn Tipton once said about the guitar solos in Judas Priest—that people tended to throw “Beyond the Realms of Death” at him (with very good reason: it may be the most perfect guitar solo in the history of the genre), forgetting that some of the best Priest solos were the ones where he and Downing traded off—I say, like a true gentleman, Demmel emphasized the same with Flynn, highlighting “Engulfed by Flames,” where the solos are linked by way of an ascending series of trills played in harmony, and which he was good enough to both sing and half-air for me, there in the parking lot of the Network.*

In the thirty-plus years between that show and today, those two Vio-lence records have never left my rotation. If I focus on Nightmare for the remainder of this post,† it’s only because I want to highlight something about it that no other thrash record does, or does to the same degree: it captures the pandemonium of a great live metal show. It sounds like what Demolition Hammer called, in one of their finest song titles, an orgy of destruction. It is the sonic correlative to what Exodus expressed so admirably in the words of the chorus to “Bonded by Blood,” and which comes closer than anything to articulating the ethos of the scene as a whole: “Murder in the front row/ The crowd starts to bang/ There’s blood upon the stage// Bang your head against the stage/ And metal takes its price/ Bonded by blood.”§

So many things about Nightmare contribute to the “live” feel. The near-impossible tempos, of course; and even more, the way the rawness of this record—a rawness that characterizes the first records of so many thrash bands—allows us to hear the musicians straining against the limits of their collective ability. Nightmare is a record that drives all over the road, swerving from guardrail to shoulder and back: we listen for the anticipated collision. That’s not to say the band isn’t tight; they could never play like this if they weren’t tight as hell. But great thrash bands like Vio-lence never made it sound easy; they made you hear the blood and sweat that went into the music. More than athletic, it was downright gladiatorial, and Vio-lence were the Conans of the pit. Alas, that scraping along the guardrail of chaos, of the abyss: it’s something you don’t hear in metal anymore. Maybe this is one reason thrash still finds listeners today, listeners who miss the sound of the body in metal.**

So many things about Nightmare contribute to the “live” feel. The near-impossible tempos, of course; and even more, the way the rawness of this record—a rawness that characterizes the first records of so many thrash bands—allows us to hear the musicians straining against the limits of their collective ability. Nightmare is a record that drives all over the road, swerving from guardrail to shoulder and back: we listen for the anticipated collision. That’s not to say the band isn’t tight; they could never play like this if they weren’t tight as hell. But great thrash bands like Vio-lence never made it sound easy; they made you hear the blood and sweat that went into the music. More than athletic, it was downright gladiatorial, and Vio-lence were the Conans of the pit. Alas, that scraping along the guardrail of chaos, of the abyss: it’s something you don’t hear in metal anymore. Maybe this is one reason thrash still finds listeners today, listeners who miss the sound of the body in metal.**

To speed we must add endurance; for Nightmare is also an absolutely relentless record, one that sustains its ludicrous tempos for far longer than seems humanly possible. Genre critics sometimes speak of “withstanding” the sonic onslaught of metal, as though the listener was proving their mettle / they’re metal by willingly putting themselves in the way of the music’s Shermanic march to the sea. According to this formulation, the longer the songs—provided they sustain a certain level of intensity—the more valiant the listener. Had Slayer written “Serial Killer,” it would have been a minute and a half long, maybe two. But “Serial Killer” clocks in at three full minutes, and the longer songs on Nightmare max out at six and a half. When, like Vio-lence, you carry on tempos like these that much longer than the typical hardcore blurt, or keep stopping and starting that motor, returning over and over to that same blistering tempo, zero to 120 in no-time flat; and when, like Vio-lence, you forego, together with your subgeneric compatriots, the (then-nascent) doubled-up tempos of death metal, which blur into a drone, for the jackhammer pounding of thrash; and when, again like Vio-lence, you sustain tempos to the point of the body going into failure, the lactic acid searing holes in muscle tissue—when you do all these things, you don’t hear the tempos so much as feel them. The music becomes brutally, pitilessly tactile.

This is a record where literally everything is done to excess. It’s not just the tempos or song lengths, or even the boxcar appearance of riff after riff, but the fact that, on some of the longer tracks, every riff gets repeated in three or four different variations before the song pauses, finds a new riff … and proceeds to squeeze out the same amount of blood out of it. Good riffs, Nightmare tells us, are built for just this sort of wear and tear.

And then a something slightly muddled about the mix adds to the stumbling near-catastrophe that is this record: the good sort of muddle that allows the guitars and bass to surge together in a single sonic tsunami. The guitars have a fat, crunchy sound—every chord sounds like stepping on a very large beetle—and Deen Dell’s bass, booming and farty, is well up in the mix. Sometimes guitars and bass operate together in a juggernaut, as in the riff that dominates “T.D.S. (Take It As You Will),” all three instruments trilling in tandem, triply heavy for charging abreast.

Listen to the surprise coda of “Bodies on Bodies,” maybe the moment on this record that best captures that feeling of centrifugality. The closing section of Metallica’s “One” makes a good foil here. The two-on-three cross-accents between chugging rhythm guitar and harmonized lead; the lockstep synchronization of rhythm guitar and snare roll at each turn: it’s brilliant, and exhilirating, and it’s what total control sounds like. The coda of “Bodies on Bodies” is the exact opposite: the turns (four hammered beats to announce a repeat) sound like afterthoughts; the accents of the rhythm guitar fall on and off the beat of the drums; the four-note phrases that climax the solo don’t match any of what the rhythm section is doing. Everybody sounds like they’re jumping in too late or too early. It’s a miracle they all manage to hit the final chord at the same time.

And what “Bodies on Bodies” does on the local level, album-ender “Kill on Command” does for the record as a whole. The last progression is repeated a half dozen times, transposed a half-step higher each time, the tempo pushed up a notch with each iteration, until—cued by a pick slide—it returns to its original register, but at the fastest tempo yet. Drummer Perry Strickland gives up at this point, he’s just whacking on his snare, and on the opposite beat (1-3 instead of 2-4); you can almost see him throwing away his sticks, throwing up his hands. It’s a perfect way to close the record, climaxed and abandoned in the same gesture. Thirty-five minutes since the Nightmare started, and no one, including the listener, is quite sure how we made it.

The madness is there for all to hear in Sean Killian’s maniacally distinctive voice, too, a voice that couldn’t be more perfectly suited to Vio-lence’s music. A friend of mine once described it as the voice of a demented carnival barker. I myself am sometimes reminded of a street vendor’s pregón, the way it rises and falls rhythmically within the same narrow range. During uptempo passages Killian’s delivery is clipped and breathless, sometimes dead center on the beat, sometimes slipping and sliding over it, not quite able to match beat to breath, once again adding to the feeling of narrowly-averted disaster. But the barker’s voice is also a matter of timbre, and tone: it’s the sneer that makes the voice, and that once again perfectly expresses the ethos of scene and subgenre: the mocking camaraderie of skate culture. We hear it most clearly in the closing words of “T.D.S.” (“No need for ties/ No ties to life/ The life you’ve left to linger/ It was your choice/ So hold your voice/ And don’t … point … your … fin-ger ….”); in the gallows humor that gives us moments like the bridge of “Calling in the Coroner (“Distorted features/ As I picked him off the road/ His body, mangled,/ Took ten hours for me to sew together …”); and in the anthemic closing lines of “Kill on Command,” where Killian, assuming the voice of a hired assassin, snarls, “Stand still, and make my job easier!”

My hardcore friends loved Killian’s voice because it was a punk voice; and so this record is, like all the best thrash, deeply hardcore-inflected as well, though more obviously and more on the surface than other non-crossover bands. Killian was a little like what Paul D’ianno was to Maiden, before Dickinson stabilized their NWOBHM identity. Vio-lence needed not to stabilize.

The dizzying back-and-forth between Killian and the riot vocals on songs like “T.D.S.” ups the ante even further, with Killian’s lines sometimes leading into or out of riot vocals (“Coroner” and “Bodies”), sometimes overlapping and sharing lyrics with them (“Kill on Command”’s “paycheck/ bloodshed/ your head” and “money, money, money, money, MONEY!”).

And then there’s the drums. Jesus. I used to chat about Strickland’s drumming with Adam Kieffer, a great drummer from my hometown and one-time member of Headlock, guitarist Adam Tranquilli’s post-Blood Feast effort. A sort of quiet awe reigned; there was a lot of head-shaking, and helpless little puffs of air.†† Thirty years down the road, I’m still looking for the words.

I’ve stressed tempo and timbre quite a bit above, but there’s a whole other side to this record, and to thrash metal, that warrants discussion: the mosh parts. Nightmare has some of the best. At shows, Killian would move his finger like he was winding a See-n’-Say, and few had the will to resist the circle that formed as naturally as a cyclone from the swirling patterns on a satellite map. When I speak about this band as the culmination of a half-decade of musical growth in a subgenre that was soon to be grunged out of existence, the idea that comes to mind is something backward-looking, traditional, the sort of band in which the finest elements coalesce and find their purest expression, rather than something that challenges the tenets of a genre and pushes its boundaries—a difference to which sociologist and metal scholar Keith Kahn-Harris has given the names mundane and transgressive cultural capital (see “T-shirts and Wittgenstein,” 05.24.13). The truth here is both-and. I could point to a dozen other bands with great grooves and amazing pits, from traditional Bay-Area stalwarts like Testament, to bands that were leaking/had leaked out in other directions/into neighboring genres, like the Tendencies, or Anthrax. The balance between speed and groove, circle and line (or many crossing lines), is what thrash evolved to perfection. But in Vio-lence, the combination of the power of their grooves and Killian’s half-spoken, highly-rhythmic vocals, as well as the interplay between his and the backing vocals, also reveals that moment when elements of rap were irrepressibly beginning to find their way into thrash metal, as these two underground musics of the ‘80s merged and mixed, into what would eventually become, post-thrash, the sound of bands like Pantera and Rage Against the Machine (and some of the later regrettable shit that smeared itself onto their coattails). While bands like Faith No More were beginning their rather dull and unconvincing experiments with crossover (now we sound like a rap band! now comes the metal part! now the pretty part, with piano! but somehow all exactly the same!!), the genre was already feeling the pull of rap on a much deeper level, inflecting the music of bands that weren’t necessarily thinking in that direction, and in ways that many fans probably couldn’t hear. A song like Slayer’s “Read Between the Lies,” on South of Heaven (1988), is inconceivable without rap (not for nothing they had moved from Metal Blade to Def Jam records in 1986). And those currents were washing back into rap, too (e.g., Public Enemy’s sample of “Angel of Death” on “Channel Zero” (from 1988’s It Takes a Nation of Millions)). Vio-lence’s 1988 compatriots Forbidden make another good reference point here: I’ve sometimes thought that Forbidden expressed the culminating fusion of thrash and the NWOBHM, but that would be to ignore a song like “Feel No Pain,” as rap-imbued a thrash metal song as ever there was.§§

I have a great memory of driving upstate to a friend’s place in Bolton Landing, by Lake George, where his parents had a cabin. Two skaters, friends of my friend’s brother, maybe three years younger than me, piled into the back of my car with their boards; my friend (also a skater) rode shotgun. One of the younger skaters in the back asked me if I liked rap. I remember being taken aback by his question. Rap was still up there with the Dead in terms of music metalheads weren’t supposed to like. (Thank goodness this still seems to be true of the Dead.) The two genres had been kept culturally so far apart that, even when I was hearing rap-inflected metal—outside the klutzy attempts at crossover like FNM, or Anthrax’s “I’m the Man” parody—I didn’t hear it, or maybe better, didn’t admit to myself I heard it. My answer must have been something like “of course not.” It’s so obvious in hindsight, as it must have been to them, those three years that separated us an eternity, at least where the ear is concerned. We listened to Vio-lence on the way up to the lake, I can’t remember what else. Not rap. I can still see the one, with his struggling beard and long, stringy hair, his board settled across his lap. Nice kids. Quiet. Almost reserved.

Anyway, if this makes Vio-lence as much a bridge band as a culmination, so be it. Probably all culminations are bridges of sorts. Listeners who are too mired in the genre simply can’t hear that, except, again, in hindsight. Others, who listened just as closely, but a little differently, and a little more openly: they just kept walking, even though they couldn’t quite see what was coming next. They’re the ones who got places.

*

I know the proclivity for ending with an(other) anecdote must be getting old, at least for the habitual reader of this blog, if I can imagine such a beast, which, hypothetically speaking, has the head of a chicken, the body of an ostrich, the legs of a capybara, and the tail of an ankylosaurus. But this is a good one, I promise, it’s worth finishing out the rest of this post, if for nothing else than to prove me wrong.

One day when I was a sophomore in college I saw these hippie kids in the cafeteria, and one of them was a girl I had a huge crush on. They were all sitting at the same table, of course, the hippie table, the one by the window, you know, the open window, and I, somewhat intrepidly, like a half-scuttled aircraft carrier, approached them, with my ratty sneakers festooned with band names and my ripped jeans and my Captain Caveman hair. (That was my nickname, or one of them; Plant Head was another.) Of course my notebook, and likely my sneakers, said VIO-LENCE in large letters. And one of them asked me, with self-righteous smugness, whether I was a fan of violence, whether I liked violence, whether I thought violence was cool or something. I mean, he didn’t say all these things, I can’t remember his exact words, but if you put these three italicized statements together you get the picture.

That look! That tone! I was being condemned, there in front of my crush.

She was the one who had attempted a second piercing of my ear a week or two before, at a party in my apartment, in the kitchen. (This might have happened after the cafeteria episode, I’m not sure, but for the sake of the anecdote let’s pretend it came first, I mean, c’mon, this was like thirty years ago.) I’m sure I initiated the whole thing. She put a cork behind my ear and started to shove the needle through the lobe. But she couldn’t finish. She was too squeamish. She sort of squealed and shook her hands in disgust. She left me there, half-penetrated. Some other unfortunate female had to finish the job, I can no longer remember who.

So there I was, in the cafeteria, standing by the hippie table, across from the girl who had been unable to finish penetrating me. I looked at her; I looked at my notebook; I looked at my sneakers. I thought of all my parents had taught me, taking me and my friends to see movies like Scanners and Humanoids from the Deep and Evil Dead and all that vile good stuff when I was a tween, and then a teen, but still too young to attend R-rated films by myself.

I was damned before I’d even made my way over to that table.

I said, Yes, of course I am a fan of violence, and walked away.

* In terms of show epiphenomena, besides this conversation, I remember Killian laughing at my hair, a huge frizzy Eye-tie fro (note aborted attempt to dignify) that had already begun to thin in the middle. But then it seems Killian himself was already well on his way to boarding the Rogaine train. Revenge, a dish best served cold. Ha! Ha! saith he-who-laughs-last. (Killian was right to laugh, of course: my hair was ridiculous.) When Vio-lence re-banded and toured for the thirtieth anniversary of Nightmare—I had the pleasure of seeing them at the Brooklyn Bazaar; I’d have much rather seen them at St Vitus—I was disappointed to find that Killian had gone the way of so many middle-aged men and shaved his head. It seemed like a particular affront given that, back in the day, skins were beating up longhairs like him at shows.

† I’m sorry to give Masses the short shrift here. Some of Vio-lence’s best songs are on it (I’m a huge fan of “Liquid Courage” myself, a personal fave), and Demmel was right to be proud of his and Flynn’s work: the leads are consistently top-notch, better than Nightmare’s; some of the work for the rhythm section (like the opening to the title track) is also standout. My only disappointment: given some of the song titles (such as the title track, and the opener “I Profit”), I always expected the lyrics to be a little more … Marxist?

Which reminds me: there’s a great article (or perhaps a great post) still to be written about progressive politics and metal. The genre tends to be pigeonholed as conservative, and while there is some truth to that, metal’s politics are much more complex and many-sided, partly a result of the longevity and diversity of the music people have called (heavy) metal, and partly a product of ideological crossover from neighboring genres. Thrash, and the extent to which it incorporated hardcore’s politics together with its pared-back sound and furious tempos, would make for a particularly interesting discussion.

§ Exodus guitarist Gary Holt explains the genesis of the song in a show at Ruthie’s Inn, the club which was the epicenter of the epicenter of the scene. (I love the irony of the name!) See Murder in the Front Row (Bazillion Points, 2012), p. 173. If you want to see this ethos translated into moving image, there’s a great performance available on YouTube of Vio-lence playing San Francisco’s Stone in 1989, which better than anything else I’ve seen captures the energy of a live show, the circuit between stage and pit.

By the way, there’s an interesting tension here between so-called album-quality live music (i.e., the band judged by how well they reproduce their sound on their records) and live-sounding recorded music (i.e., studio (as opposed to “live,” an oxymoron anyway) records judged according to whether they capture something of the experience of seeing the band live). As someone who deeply loves some bands known for playing album-quality live, I’m not really one to throw stones at the first, though I do find it a silly ideal. But I also don’t want to jump on the authenticity bandwagon here. I don’t think Nightmare is more “authentic” (or whatever) just because it captures something of the energy of live thrash metal. There are plenty of great thrash metal records that don’t do that. Nor is there any reason studio records shouldn’t take advantage of recording technology to produce the sound a band wants. I wouldn’t particularly care if every song on Eternal Nightmare took a hundred takes, was filled with overdubs, all the guitars quadruple-tracked. What matters is the sound they achieve on the final product, not how they got there. Anyway, if you want live music, go out and hear some, for fuck’s sake. At least, after we’re all vaccinated.

** In an endnote to “T-shirts and Wittgenstein” I tried to capture this shift; and, as I noted in a later post about Carcass, maybe the evolution to a more technocratic form of metal is simply an indication of cultural evolution around the way we imagine and perceive of the body. See “Flesh Against Steel,” 04.12.17.

As for embodied metal: I think I’m riffing on Linda Williams here—think, because I didn’t make the connection until later. In a germinal film studies essay, Williams aligned melodrama, horror, and pornography as the three “body genres,” all of which are to one degree or another unseemly to the mainstream because of their body-associated excess, whether sexual, emotional, or violent. Critics have tended to emphasize the transgressive sexuality of rock and other pop music … but have always seemed less comfortable with the unleashed aggression of louder, heavier rock, at least when it is not channeled in a safely progressive/ “revolutionary” direction. In music, metal is the “body genre” that rounds out the junta, together with weepie love ballads and sex-infused pop and rock. You could even argue that the existence of the latter two impulses in popular music makes the appearance of metal inevitable: there could be no thrash without hair metal, and vice-versa.

†† In this context, we shouldn’t forget that death metal tempos evolved when drummers stopped doubling up on the hi-hat for every beat on the snare: if you alternated, you could double the fastest thrash tempos. The drummer in my high school thrash band called this “cheating.” Such was the view from 1986. So, in the endnote to “T-shirts and Wittgenstein” mentioned above, I described Strickland’s drumming as having an (inadvertent) swing because his stick bounces on the ride as it tries to match the tempos, yet another chaos-courting imperfection, if it can be called that.

In an illuminating discussion in her founding book on the subject, Deena Weinstein compares metal musicians’ instrumental prowess to blue-collar pride in skilled labor, and the custom in performance of demostrating mastery of their “tools,” not just sonically, but through gesture (facial expressions, arm motions, etc.). I’m making a somewhat different point here. I don’t think Vio-lence is so much interested in dramatizing virtuosity as they are in courting failure. We’re still hearing and feeling and applauding exertion, but the point isn’t to admire or even vicariously participate in the thrill of mastery, but rather in the exhiliration of mere exertion, and the attendant risk. In the sort of metal Weinstein writes about, success is a given. In Vio-lence, we careen along the abyss without guarantees.

§§ There’s another great article (or post) still to be written (if it hasn’t been already; honestly, I’m always at least five years behind the scholarship, maybe 10), this one about the impact of rap and hip hop on thrash metal: one that looks beyond the usual proto-groove suspects, and instead examines the way the genre’s supposedly most “pure,” traditional expressions had already been inflected across the racial-culture divide of their fanbases. It’s a necessary complement to the nexus between punk and metal, which has already been beautifully explored by Steve Waksman in This Ain’t the Summer of Love (see my review, “Dr Heidegger’s Punks,” 04.17.16).