An abecedarium of unfinished posts, fledgling thoughts, broadsides, aphorisms, quotations, addenda, notes, interludes, promenades, speculations, vignettes, & other kitchen sinks; 32 in all, all newly revised & edited into easily-digestible, individually-wrapped tidbits; artfully arrang’d & illuminated by yrs. truely, HELLDRIVER.

A

Analogies. Musical models have always guided and inspired the way I think about form in fiction and creative nonfiction. Codas, for example: short, closing sections, generally following a line break, that serve as an oblique comment, sometimes in gesture, sometimes in image, on what came before. (A mentor of mine: “End on an image and don’t explain it.” He was quoting a mentor of his.) I think about the climax of Strauss’s Don Quixote: contending, shouting horns; sudden silence; and then a series of quiet, descending trills from the violins. The abrupt about-face in mood signals the hero’s approaching death. The closing move of my story “The Stability of Floating Bodies,” for example, is indebted to this. And that story’s final image, of geese crossing the sky, has an even more specific source: it was an attempt to do in language what Rush does in the closing seconds of “The Fountain of Lamneth”: a few-second crescendo-diminuendo with a light “whump” at the peak. Of course, these musical models are themselves stories; the circuit goes in both directions. But it matters, I think, that the narrative has been filtered through music, perhaps because it serves to highlight form, strain out the muck of substance.

Sometimes it’s the oeuvre of a composer I admire that inspires an analogy, such as that between two stories I wrote back-to-back several years ago and Bartók’s fourth and fifth string quartets: one a tweaked romance, the other strident and abrasive (though they were written in the opposite order, the older of the two being my quartet #5). Or perhaps this is an attempt to inflate them well beyond their actual worth, and so inspire myself to fail again, fail better.

B

Birdsongs & cadences. In “From Scarlatti to Guantanamera” (see “Domenico in the Heart,” 3.28.21, note G), musicologist Peter Manuel argues that what people hear as a satisfactory ending is at least partly culturally determined, so that, for example, the Spanish/Latin American practice of ending on IV, which a listener whose ear is conditioned to Western music may hear as somewhat irresolute, sounds perfectly fine to someone raised listening to flamenco, or to some Caribbean musics. Cultures, that is, produce their own sense of an ending. Now, is it possible there is a deeper conditioning, something we might look for in nature? I’m thinking of the animal noises in the locations where different cultures emerged, and above all, of birdsongs.

Birdsongs don’t sound like they resolve at all. Rather, they cycle; Messiaen captured this so beautifully in the fragmented, repeating texture of his Small Sketches of Birds, one of my very favorite pieces of music. In birdsongs, movement pitchwise is hard to parse, if it’s present at all. Perhaps they resolve rhythmically? What if rhythmic cadences originally underlay melodic ones, quanta where pitches naturally fit, not because of frequency ratios, because of the ratios in temporal “spacing”? What Rosetta-stone algorithm might match these ratios?

One day, maybe we’ll understand that, when composers imitate birdsongs, be it Rameau, Dolphy, or Messiaen, they are simply paying the birds back a debt owed. I can even imagine the migratory paths of birds linking the musics found along their trajectories. And maybe it’s even deeper than this, with the soundmarks of inanimate, always animated nature shaping a particular community’s sense of form. (For more on soundmarks, see “Archaeology of Noise,” 1.8.22, note D.)

C

Cheese. When I teach the captivity narrative of Mary Rowlandson, I like to mention Michael Pollan’s comments about the role of food in cultural identity. As the reader may remember, Rowlandson starts out calling the Indians’ food “filthy trash.” That is, until she starts starving; then it becomes “sweet” (thanks, of course, to the Lord). By the end she’s pulling boiled hooves out of little kids’ hands and gobbling them down herself. Anyway, Pollan uses cheese and the French as a shorthand example for the way food speaks cultural identity: the stinkier and rankier the cheese—that is, the less palatable to anyone who isn’t French—the better. In other words: cultural identity depends as much, and perhaps more, on unpalatability for those it excludes as the palatability for those it includes. This is how cultures develop an inedible rind, as it were, as well as protecting their native pungency from bleeding out. The concept works as well for music, of course: the music most unpalatable to others is what most clearly demarcates your identity; the bond of adherents to a particular genre is at least as much a product of the unpalatability of said genre’s music to those outside the circle. The distaste of the uninitiated may even be one source of aesthetic pleasure. What free-jazz lover hasn’t enjoyed the crinkled nose, the expression of incomprehension and patronizing disbelief, of some more straitlaced audience member who somehow managed to stumble into a free-jazz set—who was perhaps invited there for that very reason: to become a pillar, a sacrifice, an emblem of the outside around whose immolation we revel? (See “Torch Songs for LES,” 12.7.12.)

When we call something an acquired taste, we’re calling attention to the labor involved in retraining our receptors (and our minds) to engage with, rather than reject, an unfamiliar stimulus, as well as signaling a particular pleasure that is gained by making that effort—an effort, I should say, that is an act of free choice, not Rowlandsonian desperation. (If I were stuck on a desert island and all I had was NSYNC, would I start to like it? I want to say no, but like Rowlandson, I think after a few weeks I’d start to find it sweet, and I’d thank the Lord, too. Hell, I’d probably eat the kid along with the hoof, and thank the Lord for that, too.) As with cheese, so with cheesy: one person’s cheese is another’s fine fare. Tolstoy thought Wagner was cheesy, and many find the histrionics of flamenco (or metal) cheesy as well. Of course, genre is an imperfect boundary. I find Iced Earth unpalatable, for example—the Limburger of metal—but I have friends who absolutely wallow in the stuff.

Nothing risked, nothing gained, I always say. A certain amount of bombast, or sentiment, and you’re going to risk stinking a little. Not enough, and you’re dead boring. Me, I’ll take the cave-aged, and work backwards from there.

D

Damned by faint praise. Metallica: best cover band ever.

*

Deviance: a screed. The relationship between heavy metal and the broader culture—academic, elite, and mainstream—has always been pretty fucking weird. Take the academic: as I mentioned in “T-shirts and Wittgenstein” (5.24.13), in the ‘80s heavy metal wasn’t a style of music; it was a case study in social deviance. Academics—generally social scientists—approached the genre through so-called content analysis, i.e. “interpretation” of lyrics for clues as to the connection between metal and antisocial/sociopathic behavior. If you wanted to read anything peer-reviewed about metal in a CUNY library, you had to go to John Jay, the College of Criminal Justice. (The exception to this might be some early work on gender play in hair metal, stressing the subgenre’s indebtedness to glam rock.) Of course, the study of pop music more generally was firmly locked in content analysis, too; metal was just a particularly aggrieved version of this. Rap seems to have suffered the same indignity. Maybe it was their joint pariah status that drove the genres into each other’s arms in the late ‘80s? At least, that is, until hip hop became the darling of academy and critics alike—it’s increasingly difficult to tell the difference—and metal blew itself to pieces, and the pieces were buried in a warm place to germinate while a debauched frat-metal surfed the airwaves for a mercifully brief moment. But I’m getting sidetracked. The first full-length academic studies of the early ‘90s started to do more complex justice to to the music (Walser) and the scene (Weinstein). A decade later, thrash was revived; retro culture, which had started by gobbling up the sixties and seventies, finally made it to the eighties; monsters became misunderstood victims with whom it was cool to identify, and theorized to the point that one truly couldn’t help but pity them; metal found a new home in Brooklyn neighborhoods you couldn’t see or even train to from L’amour’s; and the genre was soon as fetishized as tattoos and black nailpolish and the X-treme Ballsiness of Facial Hair, together with a veganism more lifestyle choice than commitment to end the untold, endless suffering of our animal brethren.

I could go on—so many cultural factors help explain the mutations that have allowed metal to flourish in odd new forms in the tidal pools of the twenty-first century. But what most interests me here is metal’s acceptance by a broader mainstream culture. This seems to be recent enough, and so contrary to where we were in the eighties, as to merit special comment. (Well. Ahem. I should acknowledge that even People magazine had come around to thrash by the late eighties. I remember reading this in a doctor’s waiting room and feeling all warm & fuzzy. With one exception, of course. Can you guess? Slayer, of course. There should be a Slayer shirt that says something like “People magazine always hated us.” Maybe the roots of the genre’s downfall should be sought, not in the Black album or the death of Cliff Burton, but People’s endorsement of Master of Puppets.) Thirty-five years later, the buzzword isn’t deviance anymore. It’s empowerment. Everyone, it seems, wants to jump on the bandwagon of this once-discredited genre, to come out of some fantastical closet and reveal that, you know, they always did like metal, appearances and habits and comments to the contrary notwithstanding.

Why are people falling all over themselves to associate themselves with a genre that was once the province of pimply math nerds and shop kids, and the shop kids’ black-eyeshadowed girlfriends the pimply nerds fantasized about? Possibly because this genre, over the last decade and a half or so, has come to be recognized as a language of the disenfranchised. There is a longstanding appreciation for heavy metal in the Islamic world, as Mark LeVine documented in Heavy Metal Islam more than ten years ago. Slayer grafitti befouls billboards in Iran as much as the Bible belt. And there are micro-scenes all over the globe, as contributors to the anthology Metal Rules the Globe (Duke UP, 2011) explored and analyzed. Iron Maiden’s rabid worldwide fanbase is the envy of none other than Lady Gaga. I keep getting emails in my school inbox from some educational documentary film company advertising a movie about the Navajo metal scene and a band there that ended up recording with Flemming Rasmussen. The Sundance Film Festival this year featured a documentary, Sirens, about an all-female thrash metal band from Beirut called Slave to Sirens. In the after-film convo, one of the producers claimed that they were all metalheads there. I mean, she was wearing black, so, yeah, anything’s possible. But I admit I was a teensy bit skeptical. The filmmakers also went out of their way to stress the incredible musical talent of the young women, who are, after all, playing the sort thing that was once labeled caveman music. And so metal is no longer the knuckle-dragging Neanderthal genre of yesteryear. Today, it is the very contemporary music of vanguardist freedom-fighters, a common vocabulary of riffs, growls, shrieks and ostinatos through which they articulate their disenchantment with the status quo and their desire for liberation. The one-time dinosaurs have become velociraptors.

Well, that sounds pretty cool, right? So why the fuck am I so annoyed? I mean, empowerment beats the shit out of delinquency, doesn’t it?

I’ll tell you why the fuck I’m so annoyed. In a word: it’s patronizing, it’s hypocritical, and it once again runs roughshod over the music that, for most of the people I know who listen to it, is the only thing that matters. It’s clearly what matters to the young women in Slave for Sirens, whatever other interests the filmmakers might have.

I wonder if this shift says something about America’s inability to countenance the congenital injustice of capitalism. Lebanese fighting corruption and gender oppression is all well and good, and that young women in Beirut, for example, have found in thrash metal a voice for their anger is patronizingly endearing (i.e., their choice of means for vocalizing their anger is accepted because of their distance from American culture; a bit like the way we laugh when non-English- speakers swear). Navajo metalheads can be safely infantilized, too. But the idea that white working-class and rural Americans have a bone to pick is a lot harder for the (white) dominant capitalist culture to swallow, because it points to an ongoing economic violence which, while deeply inflected by and entangled with race, is not in itself racial. (To note that anger is misplaced onto scapegoats and manipulated by jingoistic politicians is not the same as saying it’s unjustified.) If white working-class anger is unjustifiable, its musical expression must therefore be aesthetically flawed. But the same musical vocabulary, taken up by marginalized others, confers on the music dignity, and critics hear it differently. Funny, it still sounds like metal to me. (N.B. Sorry to ignore the middle-class metalheads here. Shit’s complicated enough; I’m just scratching the surface, and am fully aware the noise I’m making is uncomfortably grating. Anyway, this is a screed. Want nuance? Move on to letter E, and/or check out “Dr. Heidegger’s Punks” (4.16.16), which has a bit more about class and metal.)

So, yeah, all this acceptance, it leaves a bad taste in my mouth. I console myself with the idea that the fawning over metal will pass like all fads; critics will find something else once disparaged to fawn over, and they and the documentary filmmakers &c. will just leave us the fuck alone with our music. I’ll be able to find those old thrash records I missed out on collecting in the used bins again, and buy them for a reasonable price, no less valuable for having passed through the hands hipsters—hell, they probably took better care of them than the plumber who listened to them in the eighties. And then I’ll be able to listen to Slave to Sirens and all these other bands not as inspiring examples of struggles against oppression, but simply because they play good fucking metal.

O to let deviance be deviance again!

P.S: I recommend Sirens, by the way. It’s a very good doc.

E

Essence. When a band or artist achieves their essence it’s always a beautiful thing. They become allegory, a transparent thing flooded with light. They achieve the form of whatever they were intended to be, which only comes into being at the moment of its achievement, but then casts a retroactive glow over their career, which we are now invited to view teleologically. As though perfection of form were so incandescent as to blind us to substance, or to make it transparent, reveal it as (mere) form itself. As though substance were no more than a frame through which perfection of form was meant to be apprehended. While these moments seem stable and permanent, this is an illusion brought about by their perfection. They are inherently unstable, like a skateboarder poised at the edge of a ramp, or those acrobatic families who form themselves into muscular houses of cards.

All this is true even for the most wretched bands.

Application: I’ve never cared for Van Halen. I’ve recently somewhat reconciled myself to David Lee Roth, but that’s between me and my conscience. I also had to distance myself from growing up in the era of Eddie Van Halen to really take stock of his genius. Anyway, if I ask, “At what moment, in what song, did Van Halen transcend their own crass misogyny and achieve the perfection of Vanhalenness?” that moment, that song, would have to be “Hot for Teacher”: the most perfect expression of the Van Halen essence. The paradox is that they do this—and it might be the only way to do this—by going full-throttle into what makes them what they are; as though identity flipped into overdrive rattled off everything that was ephemeral and contingent, like shaking dirt through a sieve to find, not nuggets of gold, but that the sieve itself is a golden mesh. The very excess of Van Halen’s puerility and narcissism and vulgarity in this song is what enables them to pull past it (N.B.: theory-heads, I’m thinking of George Bataille here). DLR was never more gross—he was on the cusp of making self-parody a career, if he hadn’t already—and Alex never more rote. But then listen again to that opening drum riff, doubled up like Zeppelin’s “Four Sticks”; listen to Roth actually acting out his pubescent mental and emotional age; listen to the boogie-woogie rhythm the band had fiddled with before but never otherwise adequately brought to the fore; listen, listen above all to Eddie, on the intro, and the way he phrases and accents the main chord progression, both clean and full-on distorted, and that main solo, of course, a master who plays with his whole body, the way Jimi did. In the video, EVH struts down a bar like I once saw the great blues guitarist Bill Wolf do at the Red Belle Saloon in Salt Lake City. But all this is just rationalization larded with nostalgia. You can’t analyze essence into its constituent parts any more that you can parse God. It’s the way the parts fit together, the way they coalesce in those four minutes, the way they capture the unselfconscious exuberance of being Van Halen, the band, that matters.

When that song comes on the radio I can almost smell it.

I remember a colleague of mine once commenting that when you watch AC/DC you see a band that believes utterly in what they’re doing, and that makes all the difference. Think “Dirty Deeds.” Think “TNT.” Think “Girls Got Rhythm.” Brainless to boot; all the clumsy bravado of toddlers. And so, so perfect. Maybe that’s all it is: an absolute, unwavering belief in one’s genius, or sexiness, or whatever, that spills over the edges of its container. And why not? They’re rock stars.

F

Fecundity. One thing that has always attracted me in art is the sense—call it an illusion—of inexhaustible fecundity of the creator. The number of gorgeous melodies Brahms crowds into a symphony; the feeling of absolute newness Sonny Rollins imparts to a solo with every chorus; the number of quirky, perfectly-drawn minor characters who populate a Dickens novel. It can provoke laughter, a sort of giddinness, like the gag with clowns getting out of a car: Where are they pulling this shit from? It’s like being tickled. It must be related to the sublime; only our consciousness of it as art, or here, the figure of the artist, provokes delight rather than terror.

G

Gravy. Metallica didn’t evolve; they congealed.

H

Hooks. Over the decade of blogging I’ve grown attached to the idea that writing about music should inhabit something of the style of the music it speaks/about; that it should attempt to be at once mimetic and critical; that, to be adequate to the task of writing about music, there should be something in the language that embodies it, however that is imagined; and that the difficulty of doing this might help articulate something of the difficulty of music criticism. (See, for example, the first endnote of “Flesh and Steel,” 4.12.17.) It’s an oblique answer to the Burnham epigraph on the main page of this blog: a vision of criticism that rubs shoulders with the form, that attempts to occupy a fruitful border without falling into either the arid objectivity of the specialist or the besotted ecstacy of the fan (or what Burnham calls “be-here-now laziness” and “emotional groping”).

A corollary to the above is that criticism should develop discourses commensurate to the styles of music it seeks to articulate. The genre should determine the discourse, not the other way around. To presume otherwise is to miss its essence, to impoverish rather than enrich the reader’s perception.

Part of my beef with the latter-day acceptance of metal by rock critics et al. (see “Deviance” above) is that the old critical language, intended to find a way to valorize three-chord pop songs, simply can’t do justice to this genre. As rock critics have attempted to describe their strange and possibly guilty new infatuation, the critical vocabulary has not been updated to register that shift. Example: in the pop-critical lexicon, “hook” means an ear-catching melody, a word of great praise, ensuring as it does lots of clicks and sing-alongs. (I’ve probably used it myself.) But is this term of critical endearment really applicable to metal? Does metal give a fuck about hooks? Only, I assume, insofar as it bows to the dictates of pop. Which, of course, some metal does, quite effectively. But then a whole lot doesn’t.

Worst-case scenario: I fear a music that is subjected to and therefore tamed by a discourse that evolved to exclude it. To judge a genre by an inappropriate standard is to be deaf to that genre’s ethos and objectives, its unique contribution to music. It’s like saying Carl Dreyer’s films have problems with pacing and could learn something from watching Fast & Furious. Or Cronenberg movies are fine, except for all the latex critters. Or Moby-Dick shows that Melville could have used an editor. At what point do you clap someone on the shoulder and say, “You know? Maybe this just isn’t for you.”

Using a word like “hooks” to describe a metal song is like trying to eat a T-bone steak with a plastic spoon. No, metal needs a critical discourse analogous to its sound. That’s what so many amateur reviewers have done with their penchant for metaphor piled on metaphor: try to capture metal’s excess through an analogous excess of language, often through mixed, clashing, and Gongoristic metaphors. (See my article“Heavy Melville” for a fuller discussion.)

More broadly, if you like metal and want to write about it, here’s my advice: fuck rock criticism. Write against the grain by consciously undermining its shibboleths. Undermine the mainstream discourse of music criticism by coloring at its edges until the edges, not the picture, are all the reader sees. Write at great length, and then yet-greater length; become the behemoth you hear. Purge the critical vocabulary about metal of all but what can really speak it. Fill it again with a vocabulary consistent to the genre, a language of metal as much as for metal. A metallic language. You want hooks? Fine. Make them bloody, dripping meathooks. Coat them in tattered flesh. Grappling hooks for pulling carcasses down a slaughterhouse chute. The creak of the chains from the half-dismembered bodies swinging from them. The whine of Leatherface’s saw. Can you hear the music yet? Can you?

I

Instrumental. In one of his New York Notes, the great jazz critic Whitney Balliett wrote this about Charlie Christian: “In the manner of all great jazz musicians, what he played became more important than the instrument itself.” A doubly contentious point, given (a) Christian’s synonymousness with the foundation of jazz guitar as a lead instrument, and (b) the guitar’s status as an instrument where devotion to the idea of virtuosity is cross-generic; for many guitarists, the instrument has acted as a sort of wedge for expanding their taste into other genres that use the guitar, and dabbling in a number of styles (as I have, with astonishing lack of aptitude). My point is that the guitar, perhaps more than any other instrument, inverts Balliett’s formula: what Christian played—the handware in his hands—has been, for many a guitarist, more important than his contribution to that genre called jazz.

From the standpoint of composition, spontaneous or otherwise, I think Balliett underemphasizes the role instruments play in shaping what comes out of them. Great music doesn’t necessarily transcend the instrument or instruments on/for which it was conceived; it may, in fact, make the instrument glaringly present in the listener’s mind. Leo Brouwer’s sonata for guitar, for example: I can’t imagine it being composed on any another instrument; the guitar itself, its droning open strings, the arrangement of its fretboard, clearly shaped the notes on the page. And what a wonderful piece of music it is! Sometimes, what sounds like harmonically-advanced composition may simply be a path of least resistance. Like: are those transposed sustained-second chords really an example of quartal harmony … or just what came out from noodling with sus-2 chords up and down the neck?

I was thinking about all this one day while watching the great fusion guitarist Wayne Krantz at one of his (what used to be) semi-regular Thursday-night gigs at the 55 Bar. His style is so guitar-focused that it’s difficult to imagine on any other instrument; like Brouwer’s sonata, one gets the impression that it could not have come into being on anything but a guitar, nor could it be successfully reproduced one another instrument—and none of this diminishes its brilliance in any way. It’s a style partly dictated by sheer economy: he stakes out one part of the neck, often beginning with just one string, four or five notes in a line, exploiting half-steps and half-bends—his left hand stays put; his fingers seem to barely move—while his right explores rhythmic possibilities and different phrasings. He builds outwards from there: notes are added atop notes in half-bars, half steps above half steps, augmented with fuller bends and note clusters, each expansion itself augmented by increasing volume and tempo as his solos wend toward a climax. The guitar does have the advantage of having more than two full octaves within easy reach, and is particularly comfortable for this sort of minimalist exploration between the seventh and twelfth frets, where Krantz bears down. (There might even be something about an instrument that complements a venue and audience: I think of patrons, myself included, ducking under the neck of Krantz’s Stratocaster on our way to and from the 55’s bathroom.)

In a broader sense, I think we should take more care to consider the role of the evolution of instruments—that once-primary technology in the creation of musical sounds—in the evolution of music, and re-imagine “greatness” not as something abstract floating above the technology of musical production, but intimately connected with it, the god in the machine. The instrument—its shape and sonority, and the relationship between it and the body that plays it, hands feet lips tongue fingers—both inspires and delimits creation. Composition is never fully divided from performance, but part of a musician’s relationship to their instrument; improvisation isn’t something that happens in the brain prior to the note, but something that flows dialectically between mind and wandering muscles, which ideally collapse into a single entity.

Does the clear bifurcation of Prokofiev’s string quartet no. 1, revealing of the pianist’s two-handed mindset, weaken or invigorate that composition? Was Bartók able to push the string quartet in new directions because, as a pianist, he heard the quartet differently, and was less familiar with the limitations of the instruments at hand? (I think of him working with the great violinists of his day to expand the possibilities of the quartet; I think, too, of the sonorities, rhythms, and melodies of the gypsy violins he recorded that also shaped those quartets … and all his music, piano included.) What happens when musicians compose at the piano, and then take those melodic sketches to their own instruments, and begin to expand them in new directions, as, say, Coltrane describes doing with Giant Steps? The currents run in multiple directions: between instruments, between cultures, cross-composing and transcription, collaborative composition and virtuoso performance, all pushing instrumental music in new directions, and the possibilities of instruments into new ranges, which, for the following generations, simply become part of that instrument’s expressive palette. No instrument is ever “pure”; it exists within a matrix of other instruments, and composers and audiences write and listen in that context: the orchestra in a Beethoven piano sonata, the cello in Sam Newsome’s horn.

And so Christian: it may be that what he played—the guitar—had a strong influence on what he played—the notes—and that it was his outre (at the time) choice of instruments—a rhythm instrument he was dragging into the front line—more than any abstract thoughtfulness about notes and chords that exerted the pressure on advancing jazz as a style of expression.

J

Jazz inversion. Listening to Mastodon’s “Mother Puncher” the other day (Remission, 2002), it occurred to me that some extreme metal music inverts the traditional rock instrumental hierarchy dividing the rhythm section (drums and bass) from the lead (guitar, voice). It’s a code writ larger than rock, though which instrument occupies what position will depend on the genre and its development. But the repetitiveness of riff-based rock, and the ostinatos of metal, have morphed the guitars into the chief vehicles of a song’s rhythmic drive. Melody is pared back to the essentials; the listener’s attention is displaced onto timbre. And then, in much the way the walking bass in jazz frees the drums to participate more fully in the constantly-changing surface of improvisation, punctuating and emphasizing rather than carrying the backbeat, so the drums in some of these early Mastodon songs are liberated to become a solo instrument that stands over and above the rest of the music: the riffs and ostinatos become a backbeat against which the drums improvise. (Of course, you need a drummer like Brann Dailor to make it work … and make it work he does. See also Gunther Schuller’s point about Duke Ellington’s orchestration in “Pressure Begets Grace,” 9.13.20.)

K

Kiev’s Gate & Old Castle. In 2009 I was present for the finals of the Van Cliburn piano competition (held in Fort Worth, Texas) when the blind Japanese pianist Nobuyuki Tsujii (or “Nobu,” as he came to be known) shared the gold medal with Haochen Zhang. When he sat to play, he would measure from both ends of the keyboard back to its middle. Then he would begin. It’s not that he never missed a note; it’s how quickly he recuperated himself in the rare instances that he did. I was fortunate to be able to hear him again a year or so later, when he played Carnegie Hall—not Zankel or the Met, where other Cliburn medalists had performed, but Stern. At that time, maybe a decade ago, he had become something of a celebrity freak, as well as a national icon. Stern was filled that night with Japanese fans, a large number of whom, I would guess, had never been to Carnegie Hall.

Nobu’s gold-medal recital at the Cliburn culminated in a powerful rendition of Beethoven’s sonata Op. 57 (“Appassionata”). The climax of the Carnegie Hall recital was Mussorgsky’s great, underperformed piano suite “Pictures at an Exhibition.”

The irony, which the Times et al. likely considered too obvious to point out, leaving it to vulgates like me to ponder: that a blind man should play a piece whose purpose is to make us see things he himself has never seen. He occupies one part of a circuit: Mussorgsky, the composer, transformed the old castle, the hut on fowl’s legs, and the great gate at Kiev, into music, apparently from paintings, some of which have been discovered; the music, when it is performed, “reconstructs” these images in the listener’s mind; the performer’s ears and fingers become the prisms through which the images are re-integrated as sound.

This is all well and good. And yet, as I listened, I couldn’t help (silently) protesting: He has never seen the castle! He has never seen any castle at all! He has never seen, will never see, the Great Gate at Kiev! (Idiot. Have you? He’s never seen a keyboard, either.) What does he see when he plays these things? What appears in his mind? What spatial clues? Does he need to, to play them magnificently? Have they been described to him? Has he run his fingers over pictures in relief, as he did the keyboard? Has he been guided to the walls of gates and castles, touched them, walked through and under them? Is it better that he not know them as image, in order to become the emotional conduit of the notes, of pure sound, with the imagistic labor meant to be performed, never by the musician, but by the listener, and perhaps not even by them? The composer, after all, is “describing” an emotion arising from the picture, not the picture itself: the grandeur of the gate; the melancholy of the castle.

Anyway, he made the great gate present. A miracle, indeed.

A series of other things occurred to me, after listening to Nobu that night. Was imagism a Trojan horse for modernism? Some parts of the “Pictures,” like “Gnomus,” and even parts of “Kiev,” sound quite tonally advanced to my ear. Like the late Romantics grasping for the nuances and ambiguities of emotion, and twisting the rules of harmony to achieve them: might the same be true for those composers attempting to musically grasp a visual text? To what extent did the lure of the image serve as an excuse for breaking traditional tonal and structural boundaries—as though running music through the circuit of another artistic medium, or by the sheer force of attraction to some other medium, bends the rules of the original medium, forces it to rethink some of its assumptions? (Not, that is, by some internal pressure—i.e., the composer feeling that the compositional rules of the time are exhausted/overly restrictive—but outside: the composer trying to “adequate” music to the pressures of another medium.) And then, once this has happened, the program element becomes vestigial, is sloughed like old skin, and this new tonal or structural thing becomes enshrined as abstract music. I think of the way some of the most bizarre experiments in music happening toward the end of the nineteenth century—not Mussorgsky, but Richard Strauss—and then Debussy, of course—were programmatic in intent. Rather than say, “I broke the rules because I wanted to”—as Debussy happily did—the composer can say, “I broke the rules because the object I was describing demanded it.” (I could probably add Wagner here: the psychological state of a character becomes the “object” whose description demands an updated harmonic language.)

Some years after jotting down the notes for the above in a journal, I encountered this passage in Lewis Rowell’s Thinking About Music: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Music (Massachusetts UP, 1983): “The episode of the herd of sheep in Strauss’s Don Quixote, which was originally criticized for being blatantly overpictorial, now takes on a new significance because of the manner in which Strauss anticipates some of the trends in musical style since the 1950s” (156).

This also seems pertinent: the avant-jazz saxophonist and composer John Zorn has remarked on the way growing up with TV—particularly cartoons—reshaped his (and other composers’) sense of continuity and compositional integrity. (The comment is from Put Blood in the Music; I probably encountered it in the book Jazzing; see “Vasudeva on the Hudson,” 11.11.18.) Music used incidentally, to express something in the action, in a disjointed, perhaps episodic form, influenced the way composers of his generation conceived of musical structure (amply on display in Naked City, for example: Zorn music for a cartoon yet to be drawn). I discussed this briefly in the post “Silent Movie” (3.25.11), where the music of silent cinema, like cartoon music, “mimes” (the word I used there) the action on screen, following and amplifying the emotional character of the moment, punctuating or highlighting bits of action, even attempting to onomatopoeaically imitate non-present diegetic noise.

Today, the logic of narrative and the image have shredded old concepts of organic unity in music. Indeed, we seem to have come full circle: image and narrative have so overtaken music as to create a new constraint; what was once an impetus for transgression (if the causal argument above holds any water) has become the stultifying norm. Here’s hoping that some maverick of abstract music finds a way out for us … some blind savior of the future …

L

Light poles & paint cans. God bless New York, right? So many musicians, in the parks, on the street corners, in the subway stations. So poorly compensated. But this one, a drummer from a little more than a decade ago, clearly knocked me out, because I jotted down some notes in my journal. (You might even remember him; you might have encountered him elsewhere, or a handful of others like him.) He set up around the corner from MOMA, a block up 6th Ave. A portly middle-aged black man with a short grey beard and wearing—the day I recorded—a green shirt. He used thick, sawed-off wooden dowels for sticks. With his left hand he played the equivalents of bass and snare: the bass was the traditional overturned plastic paint can; the snare was a metal grate trapped under his stocking foot. He also played rolls against the edge of the bucket’s bottom. His other sneaker sat on the sidewalk, his socked foot hidden inside an aluminum cannister, with the sides dented, partly so that it would lay flat, partly to have clear surfaces to beat on, like a Jamaican steel drum. He played it inside as well as out; inside, he would produce a roll by fluttering his stick, bouncing it between the sides. There was a smaller grate on the sidewalk that he played with his right hand, and an empty propane cannister, also dented in places, for flourishes. A kit as baroque as any prog rock drummer’s, and the sort of thing that must have inspired avant-jazz drummers like Mark Giuliana when they started putting together their own DIY kits. And that’s not even all: he was set up next to a lightpost, which he would occasionally use as a ride cymbal; whacking his stick against it gave out a clattering ring-tone; the whole pole hummed. And he would just as readily play the sidewalk, the cement of which gave a dry, almost woodblock sound. There were only two things he didn’t play: the shopping cart in which he carried his equipment, and the plastic tub, just out of his reach, the bottom full of crumpled bills, like dried flowers in a wastebasket. I figured that, if I stood close enough, he would try to play me, too.

There are so many. In the parks, on the street corners, in the subway stations. You’d think the city would offer some sort of dedicated housing, just for itinerant percussionists like this. You wouldn’t want to live there, maybe. But you dream about what visiting would sound like.

*

Living. The jazz composer Maria Schneider, in conversation with Ben Ratliff: “Flamenco—it makes living possible. Blues and early jazz—it made living possible.” It makes living possible. Just keep saying that to yourself about music.

M

Metal w/o metal. VH1 once did a special on the most non-metal metal moments: moments, that is, where the cock rock codpiece dropped off, and the most beloved practitioners of the genre reveal themselves as the divas, whiners, and poseurs they really are. I wonder: What about the opposite: where ostensibly non-metal artists—and non-artists—suddenly reveal themselves to be, like, so fucking metal? I’m thinking about a moment from The Enigma, a documentary about the pianist Svatoslav Richter, where he is performing with a Russian singer in some isolated cabin. Watching that singer, my first thought was: Holy shit. That dude is SO fucking metal! But what exactly did I mean by that? What is metal, if it can be identified in moments that have nothing to do with the genre of music it purports to name? The sociologist Keith Kahn-Harris asked this question a number of years ago: can there can be metal without metal? (See “T-Shirts and Wittgenstein,” 5.24.13.) Is Robert Eggers’s new movie The Northman, like, totally fucking metal? (Indeed! (Is it good? An open question!)) Is it, then, more than just a genre, a culture that has grown up around the genre, which the music fed, and feeds, and sustains? Or perhaps just an attitude toward life and living? A full-throttle way of being present in and to the world? A presence that is the opposite of mindfulness? A marrow-sucking that never keeps us at peace? Moments of transport and sublimity, where one is at one and the same time Lovecraft’s blind, idiot god and the puny being cowering under him, threatened with his own annihilation?

*

Morning concerts: a resolution. Whereas, not all music lovers are night owls; and / Whereas, listening to music in the morning, even to jazz or metal, is neither lurid nor indulgent; and / Whereas, the metal breakfast, like the jazz breakfast, should be no more a thing of shame than the 6 a.m. Brandenburg concerto; and / Whereas, lunchtime concerts have found appreciative audiences around the city, and in no way equate to midday cocktails or pints, and are indeed often held in churches, possibly to make the patrons feel better about indulging themselves, and to give churches something to do on weekdays; and / Whereas, currently the earliest concerts seem to be at 11 a.m., and these generally on Sundays, as though they were surrogate services; and / Whereas, people have long used music, usually the radio, thas an alarm for waking, like farmers use roosters, like platoons use bugle-players; and / Whereas, a significant minority of jazz fans are so-called morning people; and / Whereas, many of us take our music as seriously as our coffee, which is to say, very seriously indeed; therefore be it / Resolved, that cities and towns around the country will make an earnest effort to offer concerts in the mornings, particularly on weekdays, between 6 and 9 a.m.; and be it futher / Resolved, that said cities and towns will revise zoning and noise-ordinance laws to accommodate said concerts; and be it finally / Resolved, that said cities and towns will foster a culture of morning musical appreciation and of combating prejudices against enjoying live music, particularly that of certain genres, before noon.

N

Nostalgias. As a child of the eighties—by which I mean my teenage years, those crucial years for the formation of musical taste—I get tired of hearing about the previous generation’s disappointment with post-sixties music. I’ve started to wonder if it’s not misdirected bitterness at that generation’s sense of their own failure. The revolution fizzled; the purported inferiority of the next generation’s music becomes a vehicle for feeling good about one’s own. I’m with Jello here: I loathe sixties nostalgia. I also hate this sort of editorializing periodization, and the vulgar Marxism and flawed isomorphism that assumes periods of conservative ascendancy couldn’t possibly produce anything of cultural value. As though the Zeitgeist was margarine, evenly spread throughout society, and hence either uniformly oppressive or uniformly liberating. Great music has always been around; genius, as somebody once said, is common as dirt. Scratch a little and you’ll find it.

The annoyance goes both ways: I get just as tired hearing my friends talk about how the eighties were the greatest period of rock bar none. I tell them how bad a drug nostalgia is, how they need to expand their horizons, buy some new records, go to a club, drink a glass of milk for fuck’s sake. Then I’ll sit down with some geriatric flower child telling me about how everything after the ‘60s sucked and how the ‘80s were the worst period ever, and I find myself defending the ‘80s tooth and nail—I mean, not hair metal or The Thompson Twins or anything, but you know. Ideally, I shouldn’t have to do either. Ideally, everybody would just shut the fuck up and listen to everybody else’s music.

But here’s a caveat in favor of the geriatric flower child. There’s something to be said for the way a greater or lesser degree of liberation in a society as a whole enables an across-the-board flourishing in the arts. A cultural rift like the one the U.S. saw in the ‘60s allows certain things to percolate up into consciousness that couldn’t otherwise. It has to. I get that. I could point to a lot of things from that era, but for some reason the text that always jumps to mind is Marat/Sade.

It has a transgressively weird quality that feels like a litmus test for an era. Could anyone make a Marat/Sade today? I sort of doubt it. As those weird-city bumper stickers suggest, we might be a bit too self-conscious, a bit too desperate, about our desire to be weird.

I’m still wary of writing off any period, or, for that matter, equating the art of any one period with the dominant culture. There’s always too much variation, too much going on. Anyway, as artists, we can’t sit around wringing our hands because asshole #143 is in the White House, and we can’t be looking around waiting for someone to start the revolution. The revolution starts one word, one note at a time. Grab the typewriter and go, man.

O

Overheard at Overkill. Circa 2014: “I was a hundred pounds lighter the last time I saw Overkill.”

P

Praised by faint blame. Megadeth: worst cover band ever.

*

Purloined clave. The clave, or key, in Latin music can refer to one of two things: a basic rhythm undergirding the music, its backbeat; or the percussion instrument (generally two thick wooden sticks) on which that rhythm is carried. If I remember my conga teachers correctly, different cultures have different claves—the clave in Brazilian music, for example, is not the same as in Puerto Rico. The clave in Puerto Rican music also comes in different times, 6:8 and 4:4. Same basic pattern—5 notes spread 2-3 over two measures—very different feel. When we think clave, though, we usually think of the 4:4 version of a basic salsa tune; anyone familiar with zydeco music, or its popularization in songs like George Thoroughgood’s “Who Do You Love,” knows the rhythm I’m talking about: BAM, BAM, BAM: BAM BAM! (N.B. If you want to hear the 6:8 clave at its awesomest, listen to Jerry Gonzalez’s Obatalá.)

But the Thoroughgood example also calls our attention to just how ubiquitous this rhythm is. It pops up in places where you least expect it, places much further afield than zydeco-infused rock. Once I learned the clave, I’d put on songs I’d been listening to for years, decades even, and it would suddenly occur to me: “Oh, wait, that’s clave rhythm!” A beat might be dropped in one of the two measures, but the rhythm was unmistakable. It’s particularly interesting when the clave appears in songs that are not making an obvious nod to Caribbean or “island” rhythms, the way The Who’s “Magic Bus” does, or the beach-punk vibe of a song like “I Want Candy” by Bow Wow Wow. Primus’s “John the Fisherman,” The Beastie Boys’s “Paul Revere,” NWA’s “Gangsta Gangsta,” Guns N’ Roses’s “Mr. Brownstone,” Led Zeppelin’s “Custard Pie,” and Carcass’s “Captive Bolt Pistol” are all clave-based. From death metal to classic rock, from alt rock to gangsta rap, once you hear that clave, you can’t un-hear it. Hence my choice of the word “purloined,” recalling Poe’s great detective story about a letter hidden in plain sight: the clave will often be there, staring us right in the face, but we won’t see it, because the genre in which it appears, so far flung from the clave’s natural environment, has rendered it inaudible.

(A fun experiment: try clapping the clave over songs where it absolutely does not fit!)

Q

Quiet. It’s easy enough to count rock songs that are paeans to the loudness that, at least once upon a time, was a defining trait of the genre. I remember the great violinist and worldwide musical ambassador Yehudi Menuhin noting that a Rolling Stones concert was the first live musical experience that had actually caused him pain. Stones aside, AC/DC’s “Rock and Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution” is my go-to loudness-themed anthem. (AC/DC may have more loudness-themed songs than any other band.) The slogan of WSOU, Seton Hall University’s metal-dedicated college station: the loudest rock. There was even a Japanese hair-metal band from the ‘80s called Loudness. Remember them?

That acknowledged, I’d like to put in a word for those rock songs that retain—and perhaps even gain—power when they are played softly. Judas Priest’s “Headin’ Out to the Highway,” for example: the lower the volume, the more power it has. I’m not sure why; maybe something to do with the song’s feeling of restraint, of anticipation. I’m reminded of what Miles once said about Rodrigo’s Concierto de Aranjuez, which he recorded a version of (arranged by Gil Evans) on Sketches of Spain, that anomalously-perfect meshing of Spanish music and jazz: “That melody is so strong that the softer you play it, the stronger it gets, and the stronger you play it, the weaker it gets.”

R

Reciprocity. One day when I was visiting my parents, my mother told me that the Prokofiev piano sonatas I’d burned for her and my father hadn’t left the boombox in the kitchen. They were on heavy rotation, so to speak. I was moved by her comment; I owe so much of my musical education to my parents, and giving some of that back was a small way to repay them. (And it wasn’t easy. They’re picky as hell.) It’s just one example of the circulation of musical gifts that has occupied so many of us throughout our lives, cementing friendships, creating bonds between and among generations, inside and outside families. The Charles Mingus and Steve Bernstein I mailed to Annapolis, and the Radiohead and Minutemen I got in return. The Anthology of Tom Waits, the title written in purple cursive by an old crush, on the flipside of a cassette label where her Japanese students had written the names of the Vanilla Ice songs they’d gifted her. I first heard Domeniconi’s “Koyunbaba” because a woman I went to grad school with who also played classical guitar taped it for me; I think I replied with Barrios; I’m no longer sure. And it’s not always music, is it. When my crazy Russian punk-rock comp student whose father taught physics at the University of Utah and whose punk rock boyfriend was a brick shithouse gave me Never Mind the Bollocks, I gifted her my library first edition of Brighton Rock (as I learned from her, Johnny Rotten’s persona was based on the thug in that book). I think of the mixes my partner made for me when I went abroad, and that my oldest friend made for me while we were all away at college, and even a tape the guitarist from my high school metal band and I sent back and forth, recording bits of songs we were working on; at the end of each recorded but we would say, “Your turn, [name]”—we recorded after, not over. Music to measure and ease and shorten distance. Handholds for long-distance relationships. I have so many cassettes with other people’s handwriting on them, and doodles, too. They’re as good as old letters, maybe better.

It’s not the same today, whatever people say. Old emails saved to a file aren’t letters. Circulation without objects isn’t circulation. The financialization of music is complete; the value of music itself has depreciated.

*

Rondo. I love the complete abandon of early thrash records to what might be called the logic of the riff. Listening to “Voracious Souls” the other day (Death Angel, The Ultraviolence), I thought about the musical form called a rondo. Instead of traditional verse-chorus-bridge structure, “Voracious Souls” uses every chorus as an excuse to strike out into new musical territory: not one but a slew of bridges, each of them landing us back at a verse, and reinvigorating the song’s basic material by doing so. I’m not making a case for conscious modeling here; I think there’s just something perennially attractive about this as a structure. It’s more coherent than the kitchen-sink approach of many a metal instrumental—including the 10-minute album-titler “The Ultraviolence”—which often seem to be agglomerations of awesome riffs that could not find a home elsewhere (see “Burnt-over,” 8.3.11). That excursion-and-return, les-adieux model undergirds allmusic, however we figure home—tonic, main riff, chorus—and the rondo, in both the multiplicity of allowable excursions and the mounting power of each return, makes it transparent. (Listen to pretty much any classical concerto third movement for an example; the third movement of Beethoven’s first piano concerto is running through my head as I write this.) It’s never, as they say, the same river twice. Each excursion finds a changed home; each journey brings the traveler back to shore with new eyes and ears.

S

Slayer, Hitchens, Sade. Slayer is to metal what the Marquis de Sade is to literature: a limit case in transgression (Slayer : metal :: Sade : literature). Other bands have taken this or that element—tempo, lyrical grotesqueness, abrasiveness of timbre—and pushed it to one or another extreme. But in no other band has the overall ethos been one of transgression in its simplest, rawest form. An awfulness that radiates out from the music and seems to infect everything around it. No other band is so at home in their vileness, and so willing to wallow in it. They have no peers, few aspirants, and millions of acolytes. Is there any other band that so convincingly revels in hatred, mayhem, and death? There should be a recognized musical condition. Slayerism: disease as style.

In Christopher Hitchens’s anti-religious screed God Is Not Great there is a wonderful moment where Hitchens describes the power of Mozart’s music. (I’m sympathetic to Hitchens’s argument, don’t get me wrong; I just found the tone of the book to be overly strident, as was true of Hitchens’s later columns for The Nation, really all of his writing after 9-11.) You don’t need God, Hitchens writes, to explain great art; but—with a wink—Mozart does make you wonder. It’s not a moment of doubt, but rather a nod to the seemingly superhuman beauty of Mozart’s music, intended to reinforce our wonder at human creativity. Certainly, many of us have felt this, listening to music, staring at a painting, or reading a great novel: that there are some artists so volcanic in their imaginations, so perfect in their productions, that we are at a loss to explain them without resorting to an argument for divine intervention.

A simple substitution, a revision of Hitchens’s formula: exchange the word “Slayer” for “Mozart,” and “Devil” for “God,” and you have as good an appraisal of the force and power of Slayer’s music as I’ve ever read anywhere. I mean, you don’t need the Devil to explain Slayer … but they do make you wonder! (We might call this a theological argument for the existence of Slayer.) Perhaps Slayer forces us to contemplate a troubling possibilty: that, far from evil being the absence of God, the deity (It)self might be malign. (This pace a comment at an ALA panel on Blood Meridian I heard a number of years ago; you can see the way this book keeps coming back.) In which case, why not call it the Devil and be done with it? Slayer, an argument for the absence of God.

I’ve never found the crackpot theater of black metal particularly affecting, though I like some of the music well enough. I mean, if you need to run around burning churches and shooting your fellow band members to make me hear the darkness in your music, then your music probably sucks. I should be able to hear those churches burning in your music. Really, if your music isn’t making going to church vestigial, try again. Try harder.

*

Subdiculous. If the sublime to the ridiculous is but a step, as Napoleon or someone close to him or maybe just someone somewhat like him famously said, then the reverse must also be true; and the way we imagine art will determine which step we believe to be higher, i.e., which direction goes against the force of gravity. Unless, that is, we imagine Napoleon’s step—surely a little step; he was a little man—to be along even pavement, perhaps without even a crack in it, let alone the abyss Armstrong spanned, bouncing along the lunar surface, holding the Earth between his thumb and forefinger, humans at last able to put our puny existence in something like a true perspective.

We’re intended—I think—to imagine a step down: the embarrassing failure when what is meant to be sublime falls short; the rocket, once proudly on course, drops flaccidly back to Earth; the moon remains intact, the stars vestal virgins. Things great are balanced precariously on their greatness; their pedestals come to a point; there are no wires; the equinox happens only two days a year; one easy push, and all the apparent grandeur disappears. Time can do this, of course; Time is merciless with Art. Falling short of the sublime, a work of art reveals itself as ostentatious, desperate to impress, and the experience of aesthetic rapture is deflated. The sublime is aloof to its audience; it does not ask for our rapture; it is self-sufficient; appreciation is unnecessary. The sublime, what makes us feel tiny, ephemeral, a speck in the cosmos, against the vastness and longevity of the thing contemplated; the ridiculous, what we belittle, what we pity, what we annihilate with our derisive laughter.

I wonder if we might hang Napoleon, or at least his idea, by the boots. The point, after all, is that these two aesthetic responses are really more kindred than they appear. If we consider, not direction, a tendency to fall from a higher to a lower state, but rather a matter of simple proximity, why can’t the circuit can run both ways, oscillate, alternate, one always on the point of shading into the other? Instead of a step, why not a switch, or a coin, or a mirror? (Isn’t the figure of Napoleon himself a good indication? Was he thinking of himself when he said this? Was Marx, when tragedy became farce? Can we run Marx’s teleological class-struggle engine in reverse? Has history already done so?) An experience that provokes laughter suddenly takes on an impressive clarity: our laughter becomes giddy, we open ourselves, and suddenly we are fully present to the aesthetic experience. Or something happens in the sublime experience that suddenly pushes us away, and make us see the representation from the outside, as in a miniature diorama, and we even see ourselves, tiny, staring at the diorama, through the wrong end of the telescope.

Can a failure to be ridiculous turn sublime? Or perhaps an exceedingly successful ridiculous? (Think of Donald O’Connor’s “Make ‘Em Laugh” routine in Singin’ in the Rain.)

We have all had these experiences, where music we love—as an insider—appears ridiculous to an outsider—or to ourselves, trying to re-engage with an aesthetic experience that had so impressed us, so moved us when we were younger. What was it, about the time, the crowd we hung with, the people we were in love with, that made it seem so? And then we can’t help but feel sorry for ourselves as we are now, resistant, unable to succumb. All the pleasure is inside; the ones outside are always unhappy, desperate. Outside is a deflated, ironized, dead world. A fallen, a disenchanted world. A moonscape.

The step is a matter of perspective. As in outer space, there is no privileged position from which one can actually tell up from down. Like an Escher engraving, the steps go in both directions. Art is always a gesture toward ridicule redeemed by faith. Surprise matters, too. The shock of the new. Again, time. We strive to lose the double consciousness of the knowing listener. (I was trying to get at something of this with my comments on a performance by Exhumed; see “Wintry Mix,” 3.20.15. And clearly, I still am.)

*

Sweat lodge. Remember The Stone? Son of Tonic. Remember Tonic? Son of The Knitting Factory. Remember the Knit? (Wait. I think it’s still there.) But about The Stone. I always admired its asceticism: devotion in brick and mortar. Like bullfights before stadiums, where the contest was carried on inside a circle of onlookers that shifted, expanded or contracted according to the movements of the spectacle it purported to contain. The Stone always felt shaped in this way by the music, by the people gathered to listen. You’ll hear other stories about how it got its name, but it was really to give it the illusion of some fixed existence beyond the essence of the music. (See “Master/class,” 11.23.12.)

The problem with a space so dedicated to listening was that they did things like turn off the AC when the music started, so that the sound of the fan wouldn’t interfere. By the end of a set—particularly when the place was full—you felt like you’d been abandoned in a container truck. Fanning yourself didn’t help much—and be careful not to crinkle your magazine when you do! Wiping yourself with your sleeve only made things worse; your shirt was soaked; you could feel the sweat trickled down your spine. You felt bad for the person who was going to take your chair for the next set; you should have brought a towel, like for an exercise bike at the gym. One night, I could clearly see the beads of sweat reflected on the arms and face of a guy leaning against the wall, who was no doubt leaving an enormous stain on the photo of Henry Grimes. (It was a Matthew Shipp set, in case that matters; he was toying with standards: “On Green Dolphin Street,” “Take the A Train,” etc.) Needless to say there weren’t any windows.

Indeed, the great trombonist Ray Anderson once called The Stone a sweat lodge, and it was considerably better the night I saw him there than some others I experienced. The term is really perfect for the sort of vision-questy feeling so many of us (adherents) have for this music. And Anderson did comment, appropriately enough, about all of us being martyrs for the music, about achieving transcendence through purification. He was playing with Bob Stewart (tuba) that night, the so-called Heavy Metal Duo. How could I let the heat hold me back?

Some years later, I saw Stewart again in the basement of the Cornelia Street Café (R.I.P., another great music space gone), and was he ever sweating—you’ve never seen a musician sweat till you’ve seen a tuba player playing New Orleans-style jazz in a hot NYC club in July. During the set, a woman threw her scarf to him to wipe the perspiration off his face. Like it was a bouquet. Stewart refused to wipe his face with it. It was all quite lovely—the scarf, the gesture, his demurring. (She told him it could be washed; he said something to the effect that they all say that.) Anyway, in the break he got a napkin from the bar instead, and he hung it on an unused music stand, right where he’d hung the scarf during the remainder of the previous set.

Just try seeing something like that at the Blue Note, or even the Vanguard. Try seeing it in the new New York. The Stone has since moved operations to the Glass Box theater at the New School, a beautiful little space, with a wall of windows looking out on 13th Street. Climate-controlled. Outside and around it, the ghosts of so many clubs. You can’t help but feel their presence when you walk around the Village. (See “Torch Songs for LES,” 12.7.12.)

T

Tabano. Every Coltrane should have his Dolphy. Consider those Vanguard recordings from 1961: whenever Coltrane’s playing gets lackluster, Dolphy’s on him like a horsefly. In one standout moment, Dolphy ends his solo with a series of cartwheeling trills on the bass clarinet—and then Coltrane enters on the soprano, trilling for what must be a good half-minute, all over the register, until Dolphy is absolutely annihilated. The imprint of Dolphy’s idea is still there, though, the raw material for Coltrane to worry.

You could call it cutting or one-upmanship, but it doesn’t feel that way. It feels more like two explorers taking turns goading each other up a mountain they’d never dare scale alone.

*

Todo tiene su final. When most people think of salsa they think of uptempo, brash, joyous dance music. This is not wrong per se, but it is limiting and somewhat patronizing, and suggestive of a legacy of racism and colonialism. Salsa is “fun” music; island people are perennially happy; they still live in the Edenic gardens Columbus described half a millennium ago; they know not the Germanic depths of tragedy, the heights of the sublime, etc.

And yet, salsa—itself a contested name—was music created by Puerto Rican immigrants during times of great hardship. If some of the upbeat joy of the music was meant as a way to escape, or, perhaps better, transmute that hardship, then something of the pain must be deeply inscribed in the music; the heights of its pleasure may simply be the negative impression of the pain it attempts to exorcise. As much as the blues, it seems to be a public working-out of a culture’s pain and angst. Wiggling your hips is not a bad way to transcend pain, and happily there’s a lot of salsa about wiggling your hips. There is also, in good pop fashion, a lot of broken hearts and sentiment. I always find myself returning to the quote from “Sonny’s Blues,” when Sonny looks out the window at a woman joyously singing at a revival meeting and tells his brother that it’s “disgusting” to think how much she must have suffered to be able to sing that way. I think, too, of Preston Sturges’s Sullivan’s Travels, where the Hollywood director of popular comedies, in an effort to make a “meaningful” film, goes undercover as a hobo, winds up in prison … and eventually comes to realize the power of comedy to transcend pain, in this case of the Great Depression. Comedy is simply another form of catharsis, laughter no less dignified than tears. There is, in fact, something more deeply human about it: rather than kowtow to Fate and the gods, we disarm them, belittle them.

That tragedy is a more elevated genre than comedy; that, in order to make salsa “serious” music, I have to reveal some hint of tragedy about it; that this requires me, the ersatz (at best avocational) music critic, to dignify it: these are longstanding prejudices, pitfalls to be avoided. So when I say that there’s a fair amount of salsa about political oppression, about the trials of being an immigrant, and about death, I don’t want to be misunderstood as somehow arguing this grants the genre a dignity it otherwise lacks. Sometimes, these themes are addressed with a sneering humor meant to balk at their power. Sometimes, what comes through is an eerie fatalism that elements of salsa as a form seem to emphasize.

Consider the classic Willie Colón record Lo mato. It appeared at a time when, as Will Hermes reminds us, “Salsa wanted to travel beyond the barrio—to be seen, and to see itself, as more than just a ghetto dancehall soundtrack. It was a virtuoso music with deep history and international pedigree; it wanted respect” (24)—this with regard to Larry Harlow’s Hommy, a salsa remake of Tommy that premiered at Carnegie Hall the same year as Lo mato. Colón was salsa’s bad boy, whose album titles and covers (e.g., his debut El Malo; Cosa Nuestra, where Colón is pictured “holding his trombone like a tommy gun” (Hermes 35); on the cover of Lo mato it’s an actual pistol he holds to an old man’s head—an image, perhaps, of the assassination of the Cruz-Puente era?) figure him as el barrio’s capo de tutti capi. After Hector Lavoe’s death, in ‘77 Colón would team up with Ruben Blades, whose socially-conscious lyrics were rooted in Nueva Cancion, and he himself produce records that seemed to scream for respect and artistic recognition (Hermes: “It was not usual ‘Baile!’ business” (223)).

But—much as I love Blades, with and without Colón—one hardly needs so-called symphonic salsa to hear the so-called Germanic darkness, tragedy and fatalism undergirding Colón’s phenomenal work with Lavoe on Lo mato. The album is about the harsh realities of el barrio, about toughs and street crime, machismo and bravado and stolen lovers, grim, sassy, and sometimes very funny (e.g., “Lola, please advise your boyfriend that, while he may have a machete … I have a machine gun.”). For me, though, “El dia de suerte” is the standout track for demonstrating how this upbeat dance music can tilt into something darker. The story of a hard-luck case who can’t seem to give up hope, its message is rendered all the more persistent both by the song’s stepladder melody and by its cycling over and over through the chorus: “Pronto llegará/ El día de mi suerte/ Se que antes de mi muerte/Seguro que my suerte cambiará” (Soon my lucky day will come; I’m sure that, before I die, my luck is going to change”) The chorus opens the song, and punctuates the six verses used to tell our hero’s life. Is this grit and perseverence, or just plain delusion? But then this is the reality of el barrio: if you don’t think things are going to get better, no matter how slim your chances—if you stop fighting—you won’t survive. It’s the chorus—the voice of the community—that reminds him of this, that bucks him up. But our hero remains uncertain; while Lavoe leads into two choruses with affirmation (e.g., “Y ya lo verá”: you’ll see), four times he asks the question that lingers over the chorus’s certainty: “Pero cuándo será?” (But when?) Even Lavoe’s teletype-style delivery suggests the broader, implacable engine of a malign fate that “betrays” him, over and over and over. This tension between hope and despair, will and fatalism, is inscribed in the form of salsa itself: the trading between chorus and sonero, chorós and tragic hero (though their roles in classical tragedy are inverted), community and striving individual trying to make it in America. Taken together with songs like “Todo tiene su final” and “Calle luna calle sol,” the tension rises above el barrio itself to become a broader statement of the human predicament, something closer to Ruben Dario’s great poem “El fatalismo.” (I know, I’m not supposed to say shit is universal anymore. But there it is.) No surprise that “Suerte” ends without resolving, the horns cut off in mid-phrase; the record absolutely needs the seven-minute “Junio ‘73” descarga at the end to bring about true catharsis.

U

Unity. One summer day in Central Park I found myself staring at a particularly beautiful tree, perhaps forty feet tall; I was just far enough away from it to be able to take it in in one view, though close enough for it to still appear majestic. I thought about one of Aristotle’s requirements for drama: the action should not last longer than a day. I wondered what was the musical equivalent to this. A tree, a tragedy, a symphony, artworks whose aesthetic pleasure results in part from an ability to consider them in the comprehensible grandeur of their totality. (NB: I misremembered unity of time as being about the spectator’s attention, not the diegesis. This is my comeuppance for artfully minimizing drama over the years so’s to have more time to teach fiction and poetry. (Sometimes I teach film instead.) I clearly need to go back to the Poetics;I could have sworn there was something in there about audience. Anyway, my apologies to Aristotle.)

V

Valentine. Chuck Billy: “You either left your old lady at home, or you drug her out to a metal show, right?” (Testament show at B.B. King’s, Valentine’s Day, 2013.) Helldriver: “Guilty as charged. I left my old lady at home. After the show, I headed up to the Broadway Dive at 101st Street and drank cocktails with a record producer while folks took turns singing songs about heartbreak from that little balcony alcove over the bar. I can’t remember where I slept; probably Metro North.”

W

Wrong guy. Think about all those records you listened to for years and years before you realized you were listening to the wrong musician. For me, it was Lenny White on those early ‘70s Al DiMeola and Return to Forever records, like Land of the Midnight Sun and Romantic Warrior. As a guitarist—as a teen—I couldn’t help but gravitate toward DiMeola’s shameless exuberance. (Okay: I still do.) Even when the jazz drummer who lived down the hall from me in college pointed out his favorite fill on “Elegant Gypsy,” I could sympathize with his passion, but I couldn’t pull my ear away from DiMeola long enough to appreciate the glittering rails White was laying down underneath him. Maybe it was the years post-college I spent listening to Max Roach and “Philly” Joe Jones, Lewis Nash and Jeff Watts, and Tony Williams, Tony Williams above all, that would make White so startlingly present to me when I put those records on again later in life. The malleability of the ear, the way what we hear changes over the course of years, as the matrix of our taste and our musical experiences shift, causes us to hear even the most familiar music differently. I’ve written about that a lot on this blog. Wisdom, perhaps: keep nostalgia and novelty in balance; use the one as a check on the other; temper the mad dash for the new with cyclical return to the old. Remember, again: it’s never the same river.

X, Y, Z

You. Thought I was going to say something else snide about Metallica. C’est fini. Ils sont morts.

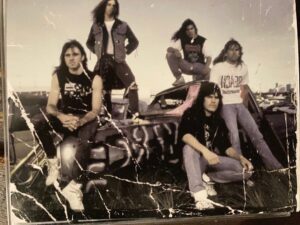

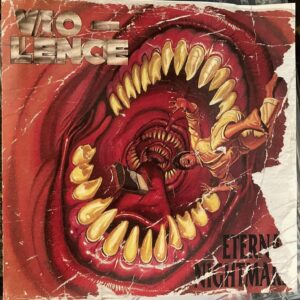

If hindsight is 20/20, then Vio-lence was the greatest thrash metal band, period: the band in which the subgenre climaxed, and in particular the Bay Area sound that was its epicenter and still, I think, its purest expression. They were the meridian of the subgenre’s day, to put it in the terms of Judge Holden from Blood Meridian, whose discourses should be compiled into a pamphlet titled How to Listen to Heavy Metal. San Andres be damned: it was that northern tribe, the Cascadians, who would shake the thrashers into the sea. Would that those San Franners had built grunge-resistant edifices …

If hindsight is 20/20, then Vio-lence was the greatest thrash metal band, period: the band in which the subgenre climaxed, and in particular the Bay Area sound that was its epicenter and still, I think, its purest expression. They were the meridian of the subgenre’s day, to put it in the terms of Judge Holden from Blood Meridian, whose discourses should be compiled into a pamphlet titled How to Listen to Heavy Metal. San Andres be damned: it was that northern tribe, the Cascadians, who would shake the thrashers into the sea. Would that those San Franners had built grunge-resistant edifices … So many things about Nightmare contribute to the “live” feel. The near-impossible tempos, of course; and even more, the way the rawness of this record—a rawness that characterizes the first records of so many thrash bands—allows us to hear the musicians straining against the limits of their collective ability. Nightmare is a record that drives all over the road, swerving from guardrail to shoulder and back: we listen for the anticipated collision. That’s not to say the band isn’t tight; they could never play like this if they weren’t tight as hell. But great thrash bands like Vio-lence never made it sound easy; they made you hear the blood and sweat that went into the music. More than athletic, it was downright gladiatorial, and Vio-lence were the Conans of the pit. Alas, that scraping along the guardrail of chaos, of the abyss: it’s something you don’t hear in metal anymore. Maybe this is one reason thrash still finds listeners today, listeners who miss the sound of the body in metal.**

So many things about Nightmare contribute to the “live” feel. The near-impossible tempos, of course; and even more, the way the rawness of this record—a rawness that characterizes the first records of so many thrash bands—allows us to hear the musicians straining against the limits of their collective ability. Nightmare is a record that drives all over the road, swerving from guardrail to shoulder and back: we listen for the anticipated collision. That’s not to say the band isn’t tight; they could never play like this if they weren’t tight as hell. But great thrash bands like Vio-lence never made it sound easy; they made you hear the blood and sweat that went into the music. More than athletic, it was downright gladiatorial, and Vio-lence were the Conans of the pit. Alas, that scraping along the guardrail of chaos, of the abyss: it’s something you don’t hear in metal anymore. Maybe this is one reason thrash still finds listeners today, listeners who miss the sound of the body in metal.** Alex Lifeson and Grace Under Pressure

Alex Lifeson and Grace Under Pressure

Carcass’s Surgical Steel is one of the best metal records of the century.

Carcass’s Surgical Steel is one of the best metal records of the century.

Listening to Carcass’s early records in chronological order is a little like watching silt settle in a pool. At first you can barely make out the objects beneath the surface; little by little they resolve themselves, until, by Heartwork (1993), they have achieved a pristine clarity. No, wait: I’ve fallen out of genre again. What on the early records sounds like a mess of undifferentiated organs—a sound that finds its visual analog in the collage that adorns Symphonies of Sickness’s (1989) record sleeve (the collage, that staple of metal record sleeves, which usually features pix of the band on stage, hanging out with friends, etc., shows instead mangled flesh and body parts: flesh-as-collage), becomes, with Necrotism (1991), autopsy and anatomy lesson. By Heartwork, the technologies of the body and of death, the body-as-machine and machine-as-body, have replaced gore as the band’s overarching metaphor, a shift captured in both tighter music and scrubbed production. From charnel house and churchyard to the dis-assembly lines of the pathology lab and abattoir, Carcass’s breakneck evolution reads like a history of Western attitudes toward death and the body. This is also evident in the albums’ cover art: from the cartoonish flesh-orgies of Reek and Sickness to Heartwork’s eerily bloodless conflation of the surgical, prosthetic, and anatomical. In this regard, Steel’s abandonment of the body for an aesthetic of the instrument, captured in its disturbingly devotional cover (pic above left), completes the trajectory begun in the late ‘80s—one reason, perhaps, that Steel is sometimes regarded as the long-deferred “true” follow-up to Heartwork, with Swansong (1995) indicative of the band’s—and the genre’s—demise.