Near the start of his perfect little book about New York, Colson Whitehead writes the following: “You are a New Yorker the first time you say, That used to be Munsey’s, or That used to be the Tic Toc Lounge” (3).* Here, Whitehead captures not only the way one’s sense of place is constructed through feelings of nostalgia and loss, but also the City’s pace of change and its relentless assimilation of newcomers.

*

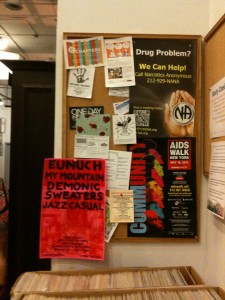

This is the bulletin board inside the Housing Works Used Bookstore Café. It used to be a payphone.

I discovered the UBC in 1997, when I worked in Tribeca. I would get off work and walk up to the Village or to midtown, and then grab a train home to Astoria. I would walk a different way every day, charting the uncharted far east and west sides. Our mental maps of the City tend to be full of blank spaces between subway stops, like those unstudied, unloved swathes of time between the periods we all read about in history classes. Biking and walking force us to account for the what happens in the spaces between the patches of the known. We come to understand much better how the City relates to itself.

I can barely remember what the old UBC looked like, back when my partner used to volunteer there, before they punched out the back wall and created that whole sitting area in the rear.

But I remember that payphone. I’m sure it was there until quite recently. The other day, I asked the volunteer at the cashier, and she claimed not to remember. Why would she? Then she humored me by saying she had a vague recollection. We constructed a whole story together around that absent payphone, like police entrapping some would-be serial killer: And then you cut the body up with a saw, right? And then you buried it in the sandbox in your neighbor’s yard, right? Yes, that’s where it was, sir. Where the bulletin board is now. I’m sure of it. How many kooks does she have to humor in this way every day? But then they are all do-gooders here, and this madness for absent payphones is harmless, mostly.

These are the trash and recycling receptacles at the Harlem 125th Street station of Metro North. Isn’t their blue newness ravishing? They used to be payphones, too. A whole bank of ‘em, at least four. Six? Possibly my nostalgia multiplies them. Not a single one of them worked. One day when I missed my train, I tried to use every phone, and every one was defective in its own special way. When I got to the last phone, and it ate my last dearly-collected dollar of quarters, I went apeshit, beat the receiver against the cradle, and left it hanging. Like Robert DeNiro does in Goodfellas when he finds out Joe Pesci got whacked. (Something about phone receivers makes them particularly well-suited to beating: snug grip, concealable-weapon size, hard plastic, all of the above?) I probably shouted “fuck,” too. Good thing there weren’t any cops around. Possibly they wouldn’t have blinked. Probably they see this sort of thing every day. The station is a hive for such mini-meltdowns. A place where high-strung commuters and the indigent mingle. The pathos of 125th Street, epic.

*

In Whitehead’s formulation: I reaffirm being a New Yorker when I say, There used to be a payphone at the Housing Works Used Bookstore Café, or, There used to be payphones at the Harlem 125th Street train station. For it is not just the first time that matters, but all the times thereafter: a ritual through which we construct and renew our sense of place and belonging. As for the payphone, it is more than a particular instance of a broader phenomenon, or an individual marker of identity, or a reference point for a number of individuals. It is representative of that vanishing City; it extends Colson’s idea from an “I” to a “we”: Here was New York, we might say, invoking E. B. White. It is through this collective act of nostalgia that we create and affirm that dream-City against which the present is measured. We might even expand Whitehead’s claim to the City as a whole: that New York became itself the moment it began to consume itself in order to become something newer, and reaffirms itself through its relentless change. Yes, this is true of every place; but it is truer of towns than villages, truer of cities than towns, and truer of New York than any other city. Partly it is a matter of size, partly age, and partly geography (e.g., New York can’t grow out, so it has to grow in, like a nail or hair).**

* The Colossus of New York: A City in Thirteen Parts. New York: Doubleday, 2003. This is a book that deserves to be on your shelf next to E. B. White’s Here Is New York. It is a perfect lyrical evocation of the City.

** Here as elsewhere on this blog, I have capitalized the word “City” to refer to New York. I do this not only to abbreviate New York City (the way we say “America” for “United States of America”), but to affirm that New York is the essence of city-ness, the ideal city, the city all other cities aspire to. If this has the same jingoistic ring that “America” has to, say, a South American (“We are all Americans,” my uncle, Argentinian, incensed, once said to me), it should.