Carcass’s Surgical Steel is one of the best metal records of the century.

Carcass’s Surgical Steel is one of the best metal records of the century.

Man, it feels good to say that. So good, in fact, that I fret I am being too conservative. Instead, I should go the whole hog, and proclaim Surgical Steel one of the great metal albums of all time … ignoring the inconvenient fact that metal has only been around for the tiniest sliver of recorded time, let alone all time. In fact, were the entire history of the human species, represented by a hair’s breadth at the end of the 360-foot-long Cosmic Pathway at the American Museum of Natural History, expanded to cover the distance of the entire Cosmic Pathway, the history of rock music would amount to just ten times that—the breadth of ten hairs!*

Of course, this should hardly make rock feel small, or metal smaller, since Beethoven, Petrarch, and even Homer don’t do noticeably better measured against deep time. So let’s drop all time and get back to the quasi-human scale.

Once upon a time, in the latter days of the twentieth century, you were only allowed to speak in the arbitrary shorthand of decades—“the greatest albums of the nineties,” “the indispensible records of the seventies,” and so on. And in the first decade of the twenty-first, you couldn’t claim anything was the “best of the century” without tongue firmly in cheek. You could, of course, more circumspectly call something “the first great record of the twenty-first century,” as though you were starting a collection of the New Century’s Great Things, and you had just gotten to put your first shiny new Great Thing in your Great Things Box, while simultaneously jettisoning everything that came before.

We are, however, living in the latter half of the second decade of this new century. Why shrink back under the flaccid umbrella of decades, and, using the much-too-silly rubrics of the “oughties” or “teenies,” pick yet another list of best albums to match yours for the nineties et al.? Why, when you have a whole new century at your disposal, and sixteen years of it behind you? Indeed, what could be more sublimely brash, more brilliantly arrogant, than sweeping judgments about a century whose second half you will never even “see,” except maybe as a pickled head, or a microchip onto which your “brain” has been downloaded?

This is a golden window, my friends. An opportunity not to be missed. Think about it: in 2019, the fiftieth anniversary of Black Sabbath will poison any best-of-new-century claims regarding metal, because everything will have to be considered in terms of metal’s hemi-centennial. By 2030, everyone will have forgotten about Y2K (huh?) and how it felt when the millennial odometer switched from 1-9-9-9 to 2-0-0-0. Then, as the century rolls forward toward 2050 (gasp!), and we approach rock’s first centenary, all new records of whatever genre will be measured against Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly, The Beatles, Stones and Who—not Judas Priest, not Metallica; certainly not Cradle of Filth.

Ergo. It’s of the utmost importance to squeeze in the most grandiose claims you can about your favorite new metal records in the next two years or so, before the inexorable march of generic time renders them obsolete.

*

Having placed Surgical Steel in one corner of my Great Things of the New Century box, the time has come to admire it. Go ahead, pick it up. Turn it in the light; run your thumb along its edge.

Ah, but Carcass is anything but a new band, or any sort of flagship for a rising genre in a new century. They’re old hat. Vintage. Okay, putrescent.§ We should talk about this.

Where metal is concerned, a few spots in my Great Things box must be reserved for so-called “comeback” records. Metal, after all, is a comeback genre. 1995, as Carcass frontman Jeff Walker declared at the band’s Gramercy Theater show last August, was “the year metal died.” (An exaggeration; but then such a tendency to mythologize is the very stuff of metal.) While emerging genres fed on its rejuvenating remains, metal was recouping its un-dead energies by feeding on the blood of those genres (how insidious, pilfering the necrophage graverobber!), as well as the flesh and bones of dead ones … including its own (how repulsive, this necrophagy-as-autophagy, this masturbatory cannibalism!). If Simon Reynolds is correct that popular culture in the new century has been played entirely in “the key of re-” (to use my old lit theory prof Henry Staten’s mnemonic for the postmodern), the re-surgence of metal was inevitable—not simply because everything comes back, but because the conservatism and tradition-worship for which the genre has been both lauded and criticized would, in the context of today’s cultural retro-faddism, suddenly seem dorkily avant-garde (or arriere-garde, as Reynolds quips).

Of course, valorizing the intrageneric past is only one part of the equation; the other parts—a scissors-and-paste attitude toward the past-as-text, and the ironic distance that accompanies it—have traditionally sat less easily with the genre. But then metal is a different genre today than it was twenty years ago, and the past is a different past: less a series of begats than an amorphous blob which, Reynolds cautions us, threatens to gobble up the present … and future.

Regardless, as a new generation of fans has taken advantage of the opportunity to explore metal’s back catalogs, so they have provided the opportunity for a number of older bands to reboot their careers. Metalographer Ian Christe traces metal’s return to the Black Sabbath reunion at the end of last century. The reappearance of some of the more successful extreme metal acts from the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, however, probably owes more to the galvanic shock provided by the thrash revival that peaked in the mid-to-late oughts. That the window of the revival appears to be closed† (occasional drafts notwithstanding) has hardly deterred a resurgent old guard from continuing to release records and/or tour with a relentlessness reminiscent of their peak years.

Among comeback records, Surgical Steel is something of an anomaly, and not only because it arrived so late in the game, after much hemming and hawing on the band’s part. With few exceptions (e.g., Anthrax’s Worship Music), comeback records tend to carry a whiff of formaldehyde, some faint, some strong enough to knock you down. And the revival stuff, good as it sometimes gets (Municipal Waste’s Hazardous Mutation and Art of Partying are probably the most lasting), still can’t help smelling a bit like something just taken out of the shrinkwrap. But Steel is all fresh maggotry: evidence of flesh well-ripened, as though the band were waiting, like forensic entomologists, to see what exactly would crawl out of their putrid hearts and jellied brains after almost two decades of delicious decay.

As much a mystery is why it landed in my lap, because this old-fart metalhead/one-time Fangoria intern never listened to Carcass in their gorelicious heyday. Even though my interest in underground metal peaked just as Carcass were appearing, they never made it onto my radar. Then, when Metallica shat themselves and the genre blew itself into shrapnel, I—like so many of the faithless in that apostate time—moved on: greedily lapping up Pantera and the occasional strong offering from Slayer and Testament, but otherwise listening to grunge and Tool and other Lollapalooza-sanctioned alt-musics, when I was listening to new rock at all. The deathiest I ever got was “cusp” bands like Demolition Hammer, and a few Deicide songs on a mix.

“What is the sword compared to the hand that wields it?” James Earl Jones as Thulsa Doom.

But such is the logic of the retro-century that Carcass and I would cross paths in our respective middle ages. I bought Steel on a whim, mostly because I saw it on somebody’s year-end best-of list (year, as opposed to decade, century, or planetary lifespan): somebody with more time, energy, new-music ADD, and/or record-industry freebies than I’ve ever had or wanted. And it was the great strength of Steel that hurtled me headlong into the flesh of early Carcass, as though to test Thulsa Doom’s great axiom, “Steel is strong; but flesh is stronger.” And if such a counter-temporal history feels twisted, I wonder how twisted it really is, in this age when so much old music is so readily available, when crowds at metal shows tend to run the gamut of generations, and when chronology, history, and to a certain extent community have been replaced by business-dominated algorithms of marketing and consumption. What follows, then, is partly about Carcass, yes; but it is as much about this Borgesian encounter with a parallel musical past, and what such retroactive discoveries mean for the way we hear and value music.

*

Seeing Carcass at the Gramercy last August was anything but a typical clubgoing experience for me. In general, for the much-loved older bands I go see in their various reunited and resurrected guises, I can put on the thousand-yard stare and talk with other old fans about having been in The Shit (= the pit at the old L’amours) back in The Eighties (= the decade which is to metal what the ‘60s is to rock as a whole; in the terms of the old Scholastic Aptitude Test, rock:’60s::metal:’80s). This is true even when part of the bill is occupied, as it so often is, and was, by a band or bands whose music I know/knew only tangentially—songs on a mixed tape someone made for me, or songs that got radio play on the college metal station WSOU (Jer-sey!), or even a video.

Given my age, then, I should have been the old Carcass fan getting his new live Carcass fix. This would have been the assumption made by most people seeing me, bald and Voivod-T’d. But by actual knowledge of the band, I was much closer to the people there half my age, whose contact with the older material would more likely be mediated by the “comeback” record. But then again, I would not hear Carcass like they did, since my formative experiences with the genre would have been much closer to those of the people there twice their age. A weird, twinned position to occupy, like I’d been split it two, but belonged nowhere: to both “halves” of the crowd, I was a fraud, a … poseur.

And yet. Still and all? It’s nice to see the good people of the kingdom of metal, even when you feel like something of an exile.

The Gramercy show was at least Carcass’s third time in the U.S. since Steel’s release. St. Vitus had sold out, as usual, and the second time around they had skipped New York. This tour, dubbed “One Foot in the Grave,” was supported by younger’uns Ghoul and Night Demon, and old-schoolers Crowbar. Jesus, Crowbar! Even they were closer to me than Carcass, if barely; I remembered a few sludgy tunes from back in the day, and pictures of a girthy man in big shorts and high-tops. And there he was! the girthy man of my youth, just grayer and maybe balder, with a second girthy man right beside him, as though from meiosis, both of them sporting Duck Dynasty beards (I know, too easy) and stomping around the stage like Japanese movie monsters. They played exactly the sort of plodding, pummeling, tuned-down music for which I vaguely remembered them; a sort of literalization of their name, so that name, look, performance, and music all cohere and flatten around the same blunt-force ethos.

At the merch tables after the set—what with four bands, there was merch spillover into the lounge—I noticed that Crowbar’s frontman (Kirk Windstein) actually has a Crowbar tattoo on the back of his neck. The placement suggests he understands the connection between the back of his neck and mortality; for it is true that I could have told his age by counting the rolls there, like tree-rings. But then on a tour of fogeys dubbed One Foot in the Grave, headlined by a dis- and (fondly) re-membered band named Carcass, mortality is by default a central theme. All those stale jokes about getting old, for example: as metal ages, and the retro-generation gives more and more old bands the opportunity to re-enter the circle, such comments are bound to become as much part of a show as headbanging. Of course, this being metal, bands tend to dramatize aging’s effects on the body in a way I just can’t imagine, say, the Stones do. Windstein, for example, bitched about (a) baldness and (b) shitting himself (not that he had shit himself, but he figured it was coming down the pike). Later, Carcass’s Walker, to goad the crowd louder, used the old saw that his hearing wasn’t so good anymore. And when, after steaming through a raft of great new material, he announced that they were going back to the early ‘90s, he dubbed it “granddad music.”Ω Again, such feints to the vicissitudes of the flesh are of a piece not just with Carcass’s music, but the genre as a whole: since bones are reverenced and tradition venerated in metal in a way that always set it apart from many other rock genres (at least, used to)—since “dinosaur” means not “passe” but “awesome”—all such comments, while apparently self-deprecating, serve as backhanded appeals to authority, just as much as Crowbar’s announcement that they had been on the road for thirty-six years.

For all the digestive angst and inverse-ironic nods to aging, Carcass were pure presence. A convincing metal act has to appear larger than life—to find a language of the body consummate with the sublimity the music aspires to—and Carcass does this with an effortlessness few bands can match. While Crowbar leveled imaginary skyscrapers, each member of Carcass stayed rooted in his particular quadrant; rather than moving, he expanded to fill it. Walker, front and center, encircled his mic in classic bassist/vocalist horse-stance (think Lemmy, or Ron Royce of the old Swedish thrashers Coroner), pointing his axe at us now and again in emulation of Father (Steve) Harris. He even turned it upside-down, like a pistol in a Tarrantino movie. I only wondered at the fan that blew on him for the duration of the show, occasionally turning him into a travesty of Fabio, or a transvestite Pippy Longstocking. From the sublime to …

I spent as much or more time watching Steer (Steer! what choice did the man have but to become the guitarist in a band that would one day sing the horrors of the abattoir?), Carcass’s other founding half, thrashing away to Walker’s left. A Perpetual Thrashing Machine he was, and the perfect complement to Walker’s Colossal Pyramid. It wasn’t regulation headbanging, but rather that horse-head-swinging that even better communicates the abandon of the music: face obscured by his blond hair, shirt half-open, skinny arms working away … it is older and deeper than thrash, older even than metal, though for me it finds its iconic representation in my memory of Ozzy’s Jake E. Lee.

At one point during the show, Walker informed security that it was okay for people to take pictures. “We don’t wear corpse paint or make-up,” he said. On the one hand, the typical metal appeal to authenticity. And yet, what was Walker saying but we look our age? He might as well have quoted that old quatrain, “Remember me now …” for those younger fans looking into the mirror of the music.‡ There was neither the urge to cheat death nor to represent it as a mask.

To be death: that is a different thing. That is Carcass.

*

But art defeats death, time’s handmaiden, does it not? I could, and probably should, write about Carcass’s career backwards, beginning with Steel, which, in my inverted listening history, acts as a template for everything that came before it, with every other Carcass record refracted through it. After all, a comeback record is only a comeback record if one comes to it with the expectations created by earlier fandom. Perhaps this helps explains why Carcass felt so present to me at the Gramercy, beyond, that is, simply the mechanics of putting on a great show, and despite the plethora of icons through which I was helpless but to see them.

With the exception of Steel, though, my impression of each individual Carcass record is contaminated as much by the ones that followed as the ones previous. Versus the one-to-two year wait between records that generally characterizes a band’s output in their historical moment, I heard Carcass’s entire early ouevre for the first time almost concurrently, and without consideration as to their historical order. To me, though they are differently dated, they are all contemporary with each other, embedded together in a spatial matrix, like coffins in a graveyard. Or, to use a better (if less Carcassian) figure: a wheel, with Steel at the hub, and the earlier records at the ends of the spokes. As such, while acknowledging that Steel acts as my hidden lens, I could, like a good historian, re-impose chronology, try to trace causes and effects, untangle threads of development, and so on. Thus:

Listening to Carcass’s early records in chronological order is a little like watching silt settle in a pool. At first you can barely make out the objects beneath the surface; little by little they resolve themselves, until, by Heartwork (1993), they have achieved a pristine clarity. No, wait: I’ve fallen out of genre again. What on the early records sounds like a mess of undifferentiated organs—a sound that finds its visual analog in the collage that adorns Symphonies of Sickness’s (1989) record sleeve (the collage, that staple of metal record sleeves, which usually features pix of the band on stage, hanging out with friends, etc., shows instead mangled flesh and body parts: flesh-as-collage), becomes, with Necrotism (1991), autopsy and anatomy lesson. By Heartwork, the technologies of the body and of death, the body-as-machine and machine-as-body, have replaced gore as the band’s overarching metaphor, a shift captured in both tighter music and scrubbed production. From charnel house and churchyard to the dis-assembly lines of the pathology lab and abattoir, Carcass’s breakneck evolution reads like a history of Western attitudes toward death and the body. This is also evident in the albums’ cover art: from the cartoonish flesh-orgies of Reek and Sickness to Heartwork’s eerily bloodless conflation of the surgical, prosthetic, and anatomical. In this regard, Steel’s abandonment of the body for an aesthetic of the instrument, captured in its disturbingly devotional cover (pic above left), completes the trajectory begun in the late ‘80s—one reason, perhaps, that Steel is sometimes regarded as the long-deferred “true” follow-up to Heartwork, with Swansong (1995) indicative of the band’s—and the genre’s—demise.

Listening to Carcass’s early records in chronological order is a little like watching silt settle in a pool. At first you can barely make out the objects beneath the surface; little by little they resolve themselves, until, by Heartwork (1993), they have achieved a pristine clarity. No, wait: I’ve fallen out of genre again. What on the early records sounds like a mess of undifferentiated organs—a sound that finds its visual analog in the collage that adorns Symphonies of Sickness’s (1989) record sleeve (the collage, that staple of metal record sleeves, which usually features pix of the band on stage, hanging out with friends, etc., shows instead mangled flesh and body parts: flesh-as-collage), becomes, with Necrotism (1991), autopsy and anatomy lesson. By Heartwork, the technologies of the body and of death, the body-as-machine and machine-as-body, have replaced gore as the band’s overarching metaphor, a shift captured in both tighter music and scrubbed production. From charnel house and churchyard to the dis-assembly lines of the pathology lab and abattoir, Carcass’s breakneck evolution reads like a history of Western attitudes toward death and the body. This is also evident in the albums’ cover art: from the cartoonish flesh-orgies of Reek and Sickness to Heartwork’s eerily bloodless conflation of the surgical, prosthetic, and anatomical. In this regard, Steel’s abandonment of the body for an aesthetic of the instrument, captured in its disturbingly devotional cover (pic above left), completes the trajectory begun in the late ‘80s—one reason, perhaps, that Steel is sometimes regarded as the long-deferred “true” follow-up to Heartwork, with Swansong (1995) indicative of the band’s—and the genre’s—demise.

How to define Carcass’s early sound? On Reek through Necrotism, gruelly and tinny on the high end, sludgy on the low; more grate than crunch, more Exodus or Megadeth than Metallica, yet much more tuned-down and unpolished than American thrash had deigned to be. Reek stands on the cusp of impenetrability, and even Sickness is in constant danger of slipping into its own murk. These first two records actually sound filthy, like the aural equivalent of trying to look at something through dirty glass. The vocals, which split thrash’s mid-range into the extremes of high-end hiss and incantatory guttural accompaniment, sound unnervingly close to an imagined black liturgy; at other times, like somebody retching—an absolutely nauseating sound. But to lump the two together is a disservice to Sickness, which expands Reek’s one-to-two minute blurts into three-to-five minute statements—and highly unpredictable statements at that, with shifting tempos and riffs metastasizing from riffs. The overall murkiness of production probably abets Sickness’s unstructured, chaotic feel, like the effect of poor light on a pattern: part bleeds into part, and recapitulations become difficult to recognize.

The eeriness and brutality of Sickness remain largely intact on Necrotism—vocally, in the guttural voice that shadows Walker’s, and in the ranting of Walker’s own, which obeys less a song’s rhythms than its own rabid logic; musically, in an even greater reliance on riff-metastasis and rhythmic instability. But Necrotism is a much more musical album than Sickness, balancing excess with greater precision (both instrumental and in terms of production), and expanding song structures into rambling suites that sometimes top the seven minute mark. They are full of false doors and non-endings; songs seem to be rising to a conclusion, with the (unexpected) re-introduction of an earlier theme, say—and then another riff will appear, another lead—the rhythm will shift a few times under said riff—and then, boom, the whole thing abruptly collapses. Thematic inventiveness and quasi una fantasia (oscura!) organization are not the only ways Necrotism broadens Sickness’s palette; there is also greater attention to texture and color: (brief) passages of undistorted guitar and effects-massaged production, and guitar harmonies redolent of the NWOBHM that Carcass had written off in the late ‘80s.

The shift from Necrotism to Heartwork is generally regarded as the most dramatic in the band’s history: a reversal of aesthetic priorities, a right-angle turn from the linear development of the first three records. Many of the songs are whittled to traditional verse-chorus-bridge structure, with introductory themes returning to fill one or another role. They also have more (and more obvious) hooks; this is a Carcass album you walk around humming. The tendrils reaching back to NWOBHM and thrash are more obvious; the sound is crunchier; and the guttural vocal accompaniment has disappeared. But as the words “more” and “many” in much of the above signal, the difference is—like the difference between Sickness and Necrotism—more one of degree than of kind. While overall slower and more controlled, Heartwork shares with its predecessor rhythmic flux (less intense, but present), athletic musicianship, and melodic inventiveness. Conversely, it is possible to see in Necrotism (if perhaps only through the lens of Heartwork) the beginnings of both a tighter melodic imagination and a more disciplined compositional style, the latter directed toward the development of a central theme rather than the willy-nilly appearance of new ones. Lesser bands have been undone in the attempt, and some greater ones as well: many of the bridges on an album as canonical as And Justice For All, for example—like Heartwork, a fourth effort—are dull precisely because Metallica seemed unable to vary or extend their central riffs imaginatively.

As noted, Swansong, while another step in Carcass’s evolution, is mostly a step backwards: the sound of a band in retreat. The lyrical subjects, so much outside Carcass’s typical obsession, sound weirdly incongruous with Walker’s vocal style; and some of the titles, at least, suggest, rather than the reckless fun of children rioting in an open cadaver (intestinal sandbox?), a tired ironizing of their earlier themes (e.g., “Keep On Rotting in the Free World”). Right from the opening arena-rock drum break, and, a few minutes later, the interjection of a cowbell—yes, cowbell—one gets the impression that this is Carcass fiddling while the genre burns. (It’s true that drum breaks are no stranger to Carcass; they go all the way back to Sickness. Perhaps, by analyzing each in turn, they might serve as a microcosm of the band’s development? Some other time, perhaps.) And while the tracks that bookend this record sound most like capitulations to the major-label powers-that-be courting some of the more successful extreme metal acts at that time, it is difficult not to generalize this feeling to the whole. With few exceptions, the record ambles along at a genial mid-tempo clip; little remains of the rhythmic variety or structural openness that gave the early records so much of their punch; songwriting and arrangements suggest a bit less the ‘80s influences that had crept into the band’s music beginning with Necrotism, a bit more ‘90s parallel afterlives (such as Rob Halford’s Fight) and ‘70s hard rock (and, in one happy instance, Sabbath). Even Steer’s solos sound watered-down, though perhaps only because he is attempting to infuse a blues-rock feel that was muted on the previous albums, to go, I presume, with the more streamlined sound.

That Swansong is sometimes regarded as a bloodless version of Heartwork points, once again, to the general consistency of Carcass’s oeuvre amid the differences. The album is certainly not without the occasional inventive bridge, strong melody, or heavy break. I want to be able to say that, if Carcass’s decadence is symbolized by Swansong’s cowbell, Surgical Steel doesn’t just get rid of the cowbell: it dismembers the very steer that rung it. But such a baby-and-bathwater take on Steel is simply incorrect. If it is indeed the album that redeems Swansong, and so Carcass’s recording history, it does so, at least partly, through inspired imitation. Particularly for the listener time-warping back from the future, some of the best material on Swansong is highly “reminiscent” of Surgical Steel, as though drafts for ideas that would come to fruition on that record. Walker has noted that Swansong represents only part of the original seventeen tracks written at the time (seventeen tracks, seventeen years: numerologists, take note!), and has claimed that some of the material not recorded for Swansong was stronger than what ended up on that record. Given the clear parallels, I can’t help but wonder to what extent Steel represents a reworking of unrecorded material from that time … and so even more that true, missing fifth album that 1995, “the year metal died,” left Carcass fans craving.

*

Considered thus summarily, the pace at which Carcass evolved (or devolved, depending on your perspective) over their original seven-year run is startling. They are generally credited with helping found two sub-subgenres: goregrind (a subset of grindcore featuring gory lyrics, often replete with medical terminology; see my “Thesaurus Metal,” 9.4.10) with their debut and sophomore efforts, and the seemingly oxymoronic melodic death metal (an offshoot of death metal with more pared-back song structures and hookier themes reminiscent of the NWOBHM) with Heartwork. As such, for some goregrind purists, true Carcass ends with Sickness, while Necrotism represents the sort of bloated excess more appropriate to prog and classic metal. More commonly, Necrotism is regarded as the peak of the band’s discography—not just an early-career capstone or transitional record, but their magnum opus. According to this narrative, Heartwork is sometimes regarded as a “sell-out” record, an about-face into the more melodic, traditionally-structured, and slickly-produced music that would bottom out on Swansong. Conversely, for fans of melodic death metal, something like Sickness (let alone Reek) is beyond the pale: Heartwork is the masterpiece, the moment when Carcass managed to fuse death metal excess with tighter, grabbier songwriting. And for those fans who appreciate all phases of the band’s brief career, there is always the relatively disappointing Swansong to signal decline. Since it is partly posthumous—the band had broken up by the time it was released—it can be fairly easily dismissed from the “authentic” discography. Once again, this creates a wound that it is all the more necessary for thrusting, stabbing Steel to retroactively fill.

A certain factionalism about Carcass’s fanbase is only logical: since founding new subgenres is generally perceived as an act of violence by adherents of the parent genre (involving, as it does, the importation of elements foreign to said genre, whether instruments, rhythms, themes, etc.; hence my preoccupation with the cowbell above), at least Reek and Heartwork would have been a sort of coup d’genre in their day. And yet, browsing through fan reviews on the web (on Amazon.com and the Encyclopedia Metallum), what stands out is the general high regard in which the band’s whole catalog is held. This is also logical, once the dates of the reviews are taken into account: the earliest ones on Amazon only go back to the late ‘90s; in the Encyclopedia, the early ‘00s. What would have appeared as a rupture in its historical moment is, once the subgenre has established itself and the new sound has found its niche in broader generic history, reabsorbed into a narrative of development; hindsight blurs what was disruptive, or at least balances it with what remains constant—as should be apparent from my own rearview sketches above. On Amazon, for example, all of Carcass’s records rate above four stars (out of five); with the exception of Reek, more than 90% of reviewers give the albums four stars and above; and scathing reviews are very infrequent. The Encyclopedia’s reviews are a bit more fractious: out of a possible 100, Sickness and Necrotism rate in the 90th percentile, Heartwork eighty, and Swansong and Reek in the mid-seventies. I will consider this difference presently. For the moment, suffice to say that, in hindsight, all pre-Steel Carcass is canonical.

In some ways, the weird new-old hybrids called “comeback” albums are even more freighted with conflicting expectations than new ones—and all the more when a band’s aesthetic is as protean as Carcass’s. The reception of Steel bears this out; perhaps it even suggests the fractiousness with which the band’s earlier records were once received, the ruptures we can no longer fully hear. In the Encyclopedia, while by and large the album receives high marks, a significant minority respond with visceral dislike, pulling the overall rating down equivalent to Swansong and Reek. The key word here is visceral. Browsing reviews of all three poorer-polling Carcass records, one finds about a third of the ratings at 50% and below. But only Steel’s reviews dip down into the single digits; one person even gives it a 0%. At least today, then, Steel is the band’s most contentious album. Perhaps this is (once again) logical: just as time would have muted and smoothed over the dislike of the other records as fans reconciled themselves to generic shifts, Steel is fresh, is now. It is almost as though one function of the “comeback” record was to give an opportunity for the earlier factionalism, so long buried, to rear its head again.

Interestingly, this is not true on Amazon, where Steel’s overall rating is the highest of any Carcass record for which a statistically significant number of reviews exist. Obviously, there is an enormous margin of error: rating systems are without a standard rubric, and on Amazon it is hard to disentangle different editions and packagings, so that negative reviews sometimes wind up being about consumer expectations rather than the music. But they are suggestive. To explain the disparity, I would guess that the reviews on Amazon include more first-time, young, and casual listeners than the Encyclopedia, many of whom would be hearing Carcass’s oeuvre from a certain distance, and perhaps (like me) mediated through a first-time encounter with Steel.

The fan-reviewers on a site like the Encyclopedia, on the other hand, clearly position themselves as connoisseurs, a metal critical elite. (This is surely also true of a subset of Amazon reviewers; they are just more diluted. Put differently: there are no blurbs in the Encyclopedia, only more or less exhaustive analyses.) And the negative reviews of Steel published there are admittedly among the best-written and most thoughtful, while the strongly positive reviews occasionally tend toward the geysering one associates with amassed teenyboppers and/or severed major arteries.

So, what are the naysayers’ chief arguments against Steel? Lack of authenticity is the big one: they accuse Carcass of pandering to fans. Why, that is, didn’t Carcass surprise us with their new record, put out something entirely unpalatable, something we were going to respect but not love, at least for the next few years? Why didn’t they once again rewrite the generic playbook? Rather than trying so hard to sound like themselves—and the point of the critique is all contained in that word like—the most authentic Carcass would sound like anything but the Carcass of old. Of course, as some of the reviews also note, the entire genre of the comeback record is compromised in this regard. As usual, Simon Reynolds captures the dilemma brilliantly: “When fans buy new albums by reformed favorites of their youth, at heart they’re not really interested in what the band might have to say now, or where the band members’ separate musical journeys might have taken them in subsequent decades; they want the band to create ‘new’ songs in their vintage style”: they want them, that is, “to cover themselves” (Retromania, p. 39).

Ironically, then, what made early Carcass good is precisely what makes new Carcass bad. Well, sort of. Because if the answer is not simply that comeback records per se are a priori crap, then one must make distinctions, judgments that show the new material at a disadvantage compared to the old. In other words: Sure, it sounds like Heartwork, BUT … it’s unmemorable, unimaginative, clichéd, you can tell they’re just phoning it in, etc., etc. It lacks, that is, those three great intangibles: a heart, a brain, the nerve.**

It’s quite possible that the way the band marketed Steel influenced how both its proponents and detractors heard it. In an interview published on Invisible Oranges the day of Steel’s release, Walker was quite candid about their approach to both the new record and their fans. Deliberating about whether to record, they had decided to see if they would come up with something that “sounded like Carcass.” Walker goes on: “We know what people want […]. We’re not stupid. We went into the rehearsal room and the studio well aware that people would have been quick to put the boot in if we didn’t deliver, you know? And at the same time we don’t want to shit on the Carcass legacy. So it’s not a cash cow. We went in using our own money. So if we weren’t confident that we could deliver on that, we wouldn’t have bothered. We weren’t going to gamble all that money away.” And, regarding how to deliver: “Play to your strengths”; “try to avoid the dumb shit and clichés”; and “give a nod [to their early career] without plagiarizing.”

Plenty of ammunition there for the aspiring cynic, to be sure. To me, though, Walker sounds more pragmatic than pandering. No matter how many powers to which the “sub” in “subgenre” is raised, it’s naïve to think that a band’s aesthetic choices are innocent of their audience’s expectations. Why would Walker divide “giving people what they want” from “avoiding the dumb shit and clichés” when, as he suggests, Carcass fans are thoughtful and discerning? Or is this flattering of the audience’s powers of discernment meta-pandering? It’s hard to tell, so much of what Walker says is generic and vague, like an athlete cornered post-game (e.g., “We just played our hardest and tried to keep a positive attitude,” etc.). As for “sounding like Carcass”: it’s true, as Reynolds says, that (most) fans want their favorite old bands to “create ‘new’ songs in their vintage style.” I am just not sure this means the comeback record as a genre is innately depraved. Clearly, Carcass took the challenge of sounding like themselves seriously: the emphasis on distinguishing self-plagiarism, for example, from the overall style and sound which, regardless of the band members’ “individual journeys,” their collective identity (in this case, Walker and Steel) gave rise to. Perhaps the comeback record should be considered a genre unto itself, one that cuts across the standard popular music genres, and is judged according to its own rules of self-performance and pastiche.

Of course, part of the point of dismissing Steel as “inauthentic” is to create a sense of the reviewer’s authenticity (hence authority), and the inauthenticity (hence ignorance) of the album’s proponents: I knew and loved the band pre-Steel; all of you who actually like this record can’t hear that the true Carcass has been replaced by a brainless, heartless, nerveless forgery. Note the implied ethics: Steel isn’t just bad music; it is cynical, manipulative, ultimately dishonest.§§

I don’t fault Steel’s detractors for dealing in intangibles. Feel, swing, inspiration: words like these pepper this post, and other posts on this blog. Anyone who writes about art is damned to deal in intangibles all the time, while desperately trying to ground intuitive judgments about such things in sensory data and paratextual materials. That said, judging Steel comes back, if I may beat the horse carcass a bit more, not to questions of taste, but of time, personal history, and perspective. Were I an old Carcass fan, maybe I, too, would smell the formaldehyde I’ve smelled on many another comeback. I might even find myself joining the small chorus of naysayers on my blog: “Ah, it’s just warmed-over Heartwork! How disappointing! How cynical of them! And look at the sheer number of times Walker mentions money!” That I am, alas, only old; that, for me, Steel is not a comeback record; that I cannot hear Necrotism or Heartwork the way they sounded when they were released—and yet, paradoxically, cannot hear them the way someone half my age does, given my experience of the milieu from which Carcass emerged: all these elements converge to influence the way I hear Steel. As is likely obvious, to these old-new ears the riffs are just as memorable (and as copious), the songwriting as snare-tight, and the technical excursions at least as impressive as the best of Carcass’s early work.†† And if it sounds like Carcass “covering themselves,” this might be because Steel, more than any other Carcass album, reminds us that early ‘90s Carcass was forging ahead in part by forging together elements from generic history: from the open letters to NWOBHM stalwarts Priest and Maiden (“1985,” which opens the record, should have been called “1982,” after Judas Priest’s “The Hellion,” the opening instrumental on Screaming for Vengeance, which it mirrors, right down to the ending gong), to the heavy, structuring, dolefully beautiful harmonies of Testament and Megadeth.

One is never without reservations. The propensity to break for a new riff on one guitar, then harmonize it in thirds, for example: it’s the sort of thing that would get old fast, if the raw material wasn’t so strong. The album isn’t perfect. So what is? When it hits its stride—as it does on the middle five tracks, with additional high-points on the earlier and later tunes—I can’t think of any metal I’d rather be listening to. And that’s saying a lot.

*

In Retromania, Reynolds blames today’s instantaneous, unlimited access to recorded music for stunting listening habits and creativity, both of which which have tended more and more toward the archival and ironic. A confessed “futurist zealot,” Reynolds despairs for the pop-music future, a future which seems to have become “unimaginable”— though he does end the book on a note of wistful hope. There is much in Retromania with which I deeply sympathize (gushing review forthcoming, someday). And yet, for those of us whose ears are relatively conservative, whose processing speeds are stuck somewhere in the dial-up era, whose adaptability to changing trends is challenged at best, and whose habit of listening recursively is deeply engrained—in fact, is affirmed to be the very stuff of what it means to listen at all … for those of us, having easy access to the plenitude of recording history is an important part of how we make sense of a recent history that seems to go by in an always-accelerating whirlybird blur.ΩΩ

I lost touch with metal as a young adult, just as it began toward the noisiest of extremes on the one hand, and toward pop musics that mostly bored me on the other. Re-discovering said genre in my mid-thirties as a dynamic new form was thrilling. But just as thrilling was the ability to go back to that lost decade and try to connect the dots with the contemporary. Mastodon’s first few records, for example, at least one of which would most certainly go in my Great Things of the New Century box, are inconceivable without Carcass’s early ‘90s records. (N.B.: Having grown up in a household where everyone we listened to was dead, I am comfortable with the idea of listening as an act of exhumation.)

Just as thrilling, however, is finding retroactive merit in things I was not prepared for at the time they appeared. I never could have enjoyed Sickness, and perhaps even Necrotism, back when those albums were released. I probably couldn’t listen to them now, were it not for the decade-long sojourn I took through free jazz, modernist classical, the postwar avant-grade, and other things often labeled non- or anti-music. (And then there was salsa, which helped break down the barriers to at least some of the pop I had once dismissed as merely frivolous.) Even Metallica had initially been a tough sell for my classically-formed ear, more comfortable with the complexity, virtuosity, and melodicism of prog rock and classic metal. My taste would have been much too orthodox, and likely too America-centric, to be able to digest the noisy assaults of the early death & grind bands from Britain. Still today I find a good deal of it unpalatable. Which is to say that the aesthetic breach dividing me from other people my age at the Gramercy show was as real as the generational one dividing me from those who could have been my kids. I want to believe that I somehow “missed out” on hearing Carcass in their prime, and mine. The truth is I was not the person that I sometimes want to imagine myself to have been (cf. “Vinyl Pasts,” 2.6.11).‡‡

So: flesh or steel? Were the person I am today to travel back in time: flesh, Necrotism, the hand that wields. But how can I, who was born into Steel, see Necrotism but as it is reflected in Steel? And yet, to give Steel absolute primacy and stability—the hub of the wheel—that isn’t entirely correct, either, because my impression of it necessarily changed after my contact with the earlier records. I can’t simply impose the logic of history onto autobiography, and by doing so efface my initial emotional response to the music. Desire and understanding are never entirely congruent. I can superimpose one upon the other, as I have tried to do here … but I cannot join them into a single, cohesive image. I know, or think I know, that Steel is closer to Heartwork, and to Swansong, than to Necrotism. But that doesn’t stop me from wanting Steel to be what Walker says it is: a union of Heartwork’s tightness and Necrotism’s riff-mill; what Gary Giddins so beautifully called the “elusive grail” of music, a form that is at once open-ended and contained; the dialectic between chaos and order, spontaneity and composition, wildness and civilization, that gives music so much of its power.***

* De rigeur exclamation point for scientific fact meant to provoke awe and wonder. Italics optional. This thought experiment brought to you by the AMNH’s Powers of Ten exhibit.

§ Since this is an extended consideration of Carcass, it will be swollen, even to bursting, with analogies to/puns about violent death, decay, and exhumation. It is the chief rule of the microgenre (practically an idiogenre) to which Carcass commentary belongs: a sort of spinoff of the band’s lyrics, as though all comments about the band were already sewn up inside the band. It is not just that I have no intention of breaking said rules; I do not think it is possible to write about Carcass in any other way. I may believe I am being clever when I say Carcass is “putrescent”; but it is actually the inexorable tendency of the discourse to search out images of and language about evisceration, laceration, contusion, etc. as soon as one begins writing about Carcass.

† Invisible Oranges dates its end to 2012. See their excellent “Re-Thrash: a Postmortem.” Regarding the 1987-or-so fetish: “At its peak, thrash was not just crossing over [with hardcore punk], it was also producing arena rock ballads and progressive rock epics while mutating into death and black metal. Thrash moves forward, literally and figuratively. It was foolhardy to try and trap that lightning in a bottle by going backwards in time.” (See my “Glee Metal,” 3.17.12, as well as “Burnt-over,” 8.3.11, for some echoes.) And this, which I blathered about in “Two Quixotes” (5.11.14): “The re-thrashers dealt in escapism, not history. If everyone in Black Tide was 20 in 2007, there is no way the members themselves remember the ’80s. Their music recalls the ’80s the way those boys have been exposed to it: through the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and SOD records. It cannot authentically recall the cultural zeitgeist of that time.” Then again: “Fantasy’s been a part of metal since the beginning—I see no objective difference between romanticizing previous lives in the viking age or in the 1980s.”

Ω This comment recalled for me one of the most endearing moments at 2013’s Heavy Metal and Popular Culture conference. One participant, who had taught a class on heavy metal to undergraduates, said that one of his students had taken the class because he wanted to understand his father better! (Is one function of the growing number of geriatric rock acts that the window of time suggested by the adage “Too old to rock ‘n’ roll, too young to die” shrinks to the merest crack, until it is only at the moment of recognition (“My God, I am too old to rock ‘n’ roll. Am I—”) that death strikes?)

‡ “Remember me as you pass by / As you are now, so once was I / As I am now, so you must be / Prepare for death and follow me.” This quatrain, which is not uncommon to see on old gravestones, is quoted by Megadeth in “Mary Jane” (on 1988’s So Far, So Good … So What?).

** Critics of Steel also point to some “cringe-worthy” lyrics, with the chorus of “Thrasher’s Abattoir” held up for particular contempt: “Hipsters and poseurs I abhor / Welcome to the thrasher’s abattoir.” Yep, bad. But I am trying to decide how this is more cringe-worthy than any of the nonsensical (but often hilarious) gibberish (replete with misspellings) that makes up the grotesquerie of early Carcass lyrics. In his defense, Walker claims said lyrics were intended to be “lighthearted”: a Pythonesque playing with gore. I’m with it. But then the same could be said about the risible couplet from “Thrasher’s Abattoir”—Steel being (according to Walker) a return to the early lyrical style that was partly abandoned on Heartwork, and entirely on Swansong. At other times, however, Walker can’t seem to decide whether he wants his lyrics to be taken seriously or not. Too much, he claims, has been made of the band’s vegetarianism; they are not trying to proselytize anyone (for which he condemns Barney Greenway of Napalm Death, Carcass’s Oedipal rival). Then what precisely is “serious” about the lyrics of Heartwork or Swansong? It doesn’t help that he is utterly disinclined (at least, within limits) to stop anyone from reading their own meanings into the lyrics—such as the I.O. interviewer’s suggestion that Surgical Steel’s lyrics are “sad,” rather than horrifically “celebratory.” It goes back to metal’s fraught relationship with politics: most try to stay out of it (grindcore as a whole and a few other individual bands excepted), while politically-charged lyrics tend toward the ambivalent (see Robert Walser’s excellent analysis of Judas Priest’s “Electric Eye,” Running With the Devil (Wesleyan UP, 1993), ps. 163-4). Walker’s caginess is thus par for the course. And yet, sometimes that caginess can sound like irresponsibility. Perhaps better not to read interviews. Perhaps better to ignore lyrics altogether.

§§ For more about the relationship between ethics and aesthetics in judging popular music, see Simon Frith, Performing Rites: On the Value of Popular Music (Harvard UP, 1996) ps. 70-74. Perhaps most germane is his discussion of authenticity, which he defines as “a perceived quality of sincerity and commitment” (71). Judging sincerity, Frith notes, “is a human as well as a musical judgment. And it also reflects our extra-musical beliefs.”

†† A few picks, so as not to clutter the text. Memorable riffs: “Noncompliance to ASTM F 899-12 Standard,” “The Granulating Dark Satanic Mills,” “Unfit for Human Consumption.” Copious riffage: the outro to “Mount of Execution”: we added this on at the end, the band seems to say, because we could. Technical brilliance: the intro to “Noncompliance” and bridge of “Captive Bolt Pistol.”

ΩΩ I am not being quite square with Reynolds here. He is most concerned (as am I) with the sort of shallow and one-dimensional toggle-listening encouraged by the web, and so would likely second my call for recursive listening and slowed-down processing. (Hilariously, with the exception of Reek, all my back-catalog listening to Carcass was on compact disc!)

‡‡ There is something about metal that aligns it with extreme sports and horror movies, fight clubs and jackass movies, drug culture, and other boy-heavy endeavors: the question “how much can you take?” looms over them all. The metal devotee is expected to push himself to listen to less and less palatable music; the less palatable, the more “heavy,” the more authentic, and the more authentic an acolyte one proves oneself to be, with the genre ideal measured against a vanishing point of volume, speed, and/or weight. And so it has always been difficult, for the metal devotee, to admit to not liking extreme metal. As per food writer Michael Pollan, it is like a French person saying, “Well, I’m sorry, but I just don’t like really stinky cheese …” (And as long as I’m footnoting, here is Greil Marcus’s perfectly apropos definition of nostalgia: “the desire to reach back and touch the person you never were” (qtd. in John Street, Music and Politics, p. 156).)

*** The tendency away from the spontaneous in metal finds its expression in the overly processed, mechanically synchronized sound of too much of the music today. Against it, the metal of thirty years ago must sound either disappointing or exhilirating, depending upon one’s age, listening background, and orientation within the genre. To this older pair of ears, the relative looseness of much early metal—not the self-conscious amateurism of punk, but the desire to push tempo and musicianship to a breaking point, and to capture rather than correct that on recordings—is where much of the power of metal derives from. I think of Lombardo’s double-bass in early Slayer (e.g., the break in “Angel of Death”); the bouncing stick on Perry Strickland’s (of Vio-lence) ride, leaping a fraction ahead just to keep tempo, and so creating an inadvertent swing; the extra beat given to Away’s fill in the reprise introduction of Voivod’s “This Is Not an Exercise.” I wonder if the virtuoso double-bass/guitar synchronization that ends Slayer’s “Mind Control” in 1994 (on which you can hear veteran drummer Paul Bostaph and the rest of the band slip out of time with each other) marks one of the last such instances where failure-as-power was allowed to remain intact. In all of the above examples, it is as though trying to run the machine full-throttle overloads it. The ultimate demonstration of power, after all, is not decibels achieved, but amplification blown: pure overload, total distortion.

The therapeutic use of distortion, particularly of the infrasonic, Crowbarian variety, begs study. Who knows but, some day, a future Dr. McCoy will run his tri-corder over some sick soul’s thorax, and instead of that little machine chirping, what will come out is … Crowbar? – Baciyelmo

What to do when, returning from the restroom after the early set of Dave Holland’s quartet at Birdland, you find Mr. Holland himself occupying the bar stool next to yours? Sit there and fidget, of course. Allow the window of opportunity to close, and the guy sitting on his other side to grab his ear. Then, sulk into your coffee, thinking about all the things you could have been saying to Dave Holland.

What to do when, returning from the restroom after the early set of Dave Holland’s quartet at Birdland, you find Mr. Holland himself occupying the bar stool next to yours? Sit there and fidget, of course. Allow the window of opportunity to close, and the guy sitting on his other side to grab his ear. Then, sulk into your coffee, thinking about all the things you could have been saying to Dave Holland. Alto saxophonist Patrick Bartley, whose Dreamweaver Society sextet played the Gallery a few Thursdays ago, also fits nicely with either interpretation. On the one hand, he is the founder of the J-music ensemble, a cross of jazz with Japanese pop and the ur-popular (among younger folk) aesthetics of anime and video games. On the other hand, he boasts an impressive resume of sidework with jazz veterans like Mulgrew Miller and Wynton Marsalis, on the latter of whose HBO YoungArts Masterclass he appeared, to much acclaim. Recording by seventeen, a Grammy nomination already under his belt, Bartley is the model young lion. He even looks a bit lion-like in his photo on the J-music website, with neatly-arranged beard and dreadlocks: a contemplative, serious young man, staring meaningfully off at some horizon.

Alto saxophonist Patrick Bartley, whose Dreamweaver Society sextet played the Gallery a few Thursdays ago, also fits nicely with either interpretation. On the one hand, he is the founder of the J-music ensemble, a cross of jazz with Japanese pop and the ur-popular (among younger folk) aesthetics of anime and video games. On the other hand, he boasts an impressive resume of sidework with jazz veterans like Mulgrew Miller and Wynton Marsalis, on the latter of whose HBO YoungArts Masterclass he appeared, to much acclaim. Recording by seventeen, a Grammy nomination already under his belt, Bartley is the model young lion. He even looks a bit lion-like in his photo on the J-music website, with neatly-arranged beard and dreadlocks: a contemplative, serious young man, staring meaningfully off at some horizon. About an hour after listening to Bartley’s sextet at the Gallery, I walked in on a quiet little pow-wow at The Stone. It might have been a sobremesa in some old artist’s parlor that I suddenly found myself semi-eavesdropping on. Marty Ehrlich was among them, as I realized a little later on—unlike with Bartley’s band, there was no sartorial riser separating musicians from audience. I recognized him when he went over to his bass clarinet and played a scale, perhaps an illustration of something he was saying. It’s enough just to hear the rich, still unjustly rare tone of the bass clarinet in a space as small as The Stone to be entranced.

About an hour after listening to Bartley’s sextet at the Gallery, I walked in on a quiet little pow-wow at The Stone. It might have been a sobremesa in some old artist’s parlor that I suddenly found myself semi-eavesdropping on. Marty Ehrlich was among them, as I realized a little later on—unlike with Bartley’s band, there was no sartorial riser separating musicians from audience. I recognized him when he went over to his bass clarinet and played a scale, perhaps an illustration of something he was saying. It’s enough just to hear the rich, still unjustly rare tone of the bass clarinet in a space as small as The Stone to be entranced. Some years ago, while I was trawling YouTube for vids to show my Writing About Music class, I dug up a clip from one of Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts from the early ’60s. These were educational programs presented and televised with the purpose of introducing the youth of the day to classical music. The youth could have asked for no better guide than the charismatic Bernstein. Somehow, though, whenever the camera deigns to look at the crowd, it finds the faces of sullen, pimpled preteens slouching dutifully next to their parents. Watching, all I could think was, “In a few years, these kids are going to be dropping acid and screwing in the mud at Woodstock.” In my mind, the black-and-white of TV’s childhood morphed into the meridianal colors of the summer of love. If you want to see an image of the end of an era in embryo, you can’t do better than these youthful faces in the crowd.

Some years ago, while I was trawling YouTube for vids to show my Writing About Music class, I dug up a clip from one of Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts from the early ’60s. These were educational programs presented and televised with the purpose of introducing the youth of the day to classical music. The youth could have asked for no better guide than the charismatic Bernstein. Somehow, though, whenever the camera deigns to look at the crowd, it finds the faces of sullen, pimpled preteens slouching dutifully next to their parents. Watching, all I could think was, “In a few years, these kids are going to be dropping acid and screwing in the mud at Woodstock.” In my mind, the black-and-white of TV’s childhood morphed into the meridianal colors of the summer of love. If you want to see an image of the end of an era in embryo, you can’t do better than these youthful faces in the crowd.

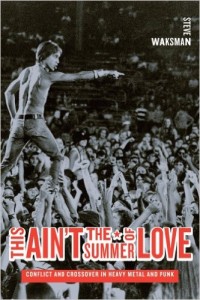

Waksman, Steve. This Ain’t the Summer of Love: Conflict and Crossover in Heavy Metal and Punk. Berkeley: California UP, 2011.

Waksman, Steve. This Ain’t the Summer of Love: Conflict and Crossover in Heavy Metal and Punk. Berkeley: California UP, 2011.