This essay about listening to Bushwick, written back in 2004-5, was originally supposed to see light through a grad school friend’s small press, Elik, now defunct. More than a decade later, a colleague turned me on to R. Murray Schafer’s The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World (1977). I must have known the word from somewhere—it appears in the first sentences of the essay—but I have no recollection where. Certainly I had no idea in ‘04 that sound studies was an established field. Anyway, I fell hard for Schafer. The Soundscape is a witty, angry, erudite, and above all beautifully-written book; it reminded me of Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death in perfectly wedding jeremiadic fervor and sardonic humor (e.g., jets are “the wounds of a crippled imagination made audible”; Muzak could only be produced in the U.S.A., “with its highly idealistic Constitution and the cruddy realities of its modern life styles”; in the factory towns of Victorian England, “workmen who experience the crucifixion of human culture then sang Messiah at Christmas in thousand-voice choirs”; or this: “The great high-rise towers of the world stand on tiptoes, looking out across the fires of the city”). But Schafer doesn’t just decry our cacophonous, tone-deaf society; his is a quixotic mission to heal society through a heightened awareness (and consequent reformation) of sound. As he explains in his introduction, The Soundscape “is about sounds that matter. In order to reveal them it may be necessary to rage against those which don’t” (12).

In posting this essay, my original idea was to completely re-do the introduction to take into account some of the theory, terminology, and analytical tools of Schafer’s foundational text, as well as a few other soundworks classic and contemporary: Jacques Attali’s Noise, published the same year as The Soundscape; recent work by Lawrence Kramer, David Rothenberg, and Anahid Kassabian. But as with the (much more recent) post about Scarlatti (“Domenico in the Heart,” 3.28.21), it made more sense to do a relatively gentle edit of the original, and use ideas from the essay as springboards for annotations that draw connections with these other texts. It might help to read keeping a wide margin in mind. (One difference with the Scarlatti: since the essay intersects multiple times with certain key ideas, several of the letters connecting passages to notes appear more than once.) In the above I am following the advice of an old writing teacher, who once said something to the effect that whatever avatar was guiding me at the time a work was completed should be respected. Put differently: I can’t go back and inhabit the self that produced this essay. In posting it, I am thus not only resurrecting Bushwick as it was at that time (2002-4), but also this younger self. Even though I find some of the theorizing about cities, art, and social class exasperating, it seemed only fair to let that self—the self who took the trouble to listen closely and put all these observations and thoughts in writing—have its say.

The essay saw a number of different titles. I think “Bushwick” was in the original; then it became “Sonic Thumbprint,” and then “Archaeology of Noise.” The final one doesn’t encompass everything the essay is trying to do, but it will have to be good enough. Two other notes: (1) I have posted the essay on both of the blog’s pages—Material/Music and The Charnel House. It is thematically at home in either space, and given its length, it deserves to bestride the Pit like the colossus it is. (2) As you read, please remember that the NOW of the essay is 2002-4, the period I lived in Bushwick, NOT2021-2!

*****

Sound buildings and sound bridges and sound streets and sound avenues. Sound parks and sound rivers and sound people people people. A city is a soundscape.A A place in soundspace. Palpable as brick and mortar, girder and rivet, asphalt, grass, stone. Stands in the same relation to you as. A city: a sonic cluster, a noise-clusterfuck. Space shapes sound, sound shapes space. Spaceshapes sound. A city. Sounds like this. Ten million souls breathing together. The sound of our blood. Wait. Leave the city. Wait for the wind to die down. Hold your breath. Now, multiply that by ten million. An artery wider than the Hudson. Then, a hurricane-breath …. This, lost beneath the clangor of the industrial and communications novae, the white-noise residue of our Big Bang ….O

As a child of the suburbs, coming into the city for a day used to exhaust me. It had nothing to do with the exertion of walking up and down the steps to the train and up and down city blocks. It was the noise. Just the noise.

Now my partner and I live in the city. In Brooklyn. To be exact—it behooves us to be exact—we live in Bushwick, a working-class Puerto Rican neighborhood in Brooklyn, with pockets of Dominicans and Mexicans, who replaced the Poles and Italians, who settled across the border in Ridgewood, Queens. The city: an archipelago held together cat’s-cradle by bridges and tunnels, each neighborhood insulated from the next—by cultural and linguistic barriers, boundaries more real and better-drawn than any official geography—and within itself, stratified according to the rhythms of settlement of different ethnicities.

To be exact: we live at 239 Stanhope Street, two blocks south of Wyckoff hospital, a few blocks from the place where the M train (elevated) crosses the L train (subway), four blocks from Queens, east of Williamsburg, north of Bed-Stuy. We live on the righthand side of the second floor of a three-floor walk-up, above a beauty parlor which used to be a salsa dance studio, in what is commonly referred to as a floor-through, meaning the apartment runs the depth of the building, from front (street, parked cars, facing buildings) to back (yard, shrubs, vacant lot, gutted and boarded-up buildings with their backs to ours, clotheslines, fire escapes).

We moved to Bushwick because we couldn’t afford the silence that the city bottles like water: the high rise, the $350-fine-for-honking sign, the zoning and traffic laws, the trees, thick walls and plate-glass windows—the insulation that is money, shredded and stuffed in your walls and ears, so you can hear your own blood-sound, not everyone else’s. We moved to Bushwick because we could afford the floor-through, dishwasher, exposed brick, hardwood floors, new bathroom—all the accoutrements of suburbohemian whiteness used to lure members of our class and our color into the dark, cacophonous hearts of the eastern boroughs.

We made the back room the bedroom, partly for security (the fire escape), partly for the noise. And though we haven’t been burgaled, we were never able to stop the noise from coming in, always uninvited, always unannounced. There wasn’t much we could do to fight it. And we didn’t fight it, not really. We got used to it. Eventually, we stopped listening.

But then one day I started listening again, to this residue, this excess, these misplaced sounds they call noise pollution. Sound as waste; sound misplaced by the strange proximity the city affords between strangers crushed into adjacent stalls, or by a volume that carries it far beyond its intended audience. Useless sound. Unwanted sound.B

And yet, whole civilizations have been described by the contents of their wastebaskets.C

If working-class neighborhoods carry the same unfair burden of noise pollution as they do pollution of other kinds, then we should make something of these riches, what city artists have always done: scavenge to create.

Every building, every block, every neighborhood—every space in this city, in all cities, and indeed every space, has a unique sonic identity, a sort of thumbprint, composed of all the audible sounds produced there over a given period of time. Some of these sounds are shared with the rest of the streets and buildings and neighborhoods, and as such are representative of the city as a whole, and perhaps cities in the abstract: a sonic fractal. Other sounds, however, are like those rare beasts found only in island ecosystems, appearing only in my building, or on my block, or in my barrio (239 Stanhope Street, 2R, Bushwick, Brooklyn). Like strange evolutionary puzzles, these purely indigenous sounds tell us the most about a place; they are the core of its identity, since they distinguish it from all other places within the city, and from all other cities … although they, too, may speak something of this city, of my city, and of all cities.D

Sounds form one cross-section of our perception, and we can use that cross-section to study the organism as a whole. That said, because New York is (like all cities) a place of wells and burrows—because you can always hear more than you can see—the sounds of a city actually reveal more than its sights. Not that we should entirely ignore the visual. Rather, we will relegate it to the same position that sound usually occupies with respect to sight. Sight mitigates our impression of the city, forcing us to shut out its voice; and it’s the voice that allows us to glimpse vistas the sights of the city hide: the palimpsests of noises mechanical and human, of waves upon waves of migration, of multiple pasts enfolded one inside another; and of the way our desires, and the whole erotic substructure built of the millions of desires inhabiting millions of contiguous cells, coalesce into a city of dreams.

The Front WindowE

We live above a commercial space whose awning defends us from the immediate sidewalk. Our building has no stoop; this might have been a conscious decision on the part of the Polish realty company that gut-renovated the building. A stoop invites a neighborhood to transact its business there. A building with a stoop wears its character in its stoop-sitters. The absence of a stoop, together with the presence of the awning, means that there is nothing to see outside our front window.* But there is plenty to hear.

The sounds that enter through our front window are the sounds of the city streets and the life on those streets. In the early morning, if we’re up and around our office, the hiss of the street cleaner, the engine, brake, and hydraulics of the garbage truck (splintering wood, crumpling plastic), and the voices of the sanitation workers, and of our neighbors as the neighborhood prods itself awake.

These, the first sounds of the day, are the sounds that signify “city,” the myth of the city, to our national consciousness. What can I tell you about these city-myth sounds that you don’t know already—you, who once lived in a city, maybe after graduating college, before starting a family; you who see cities in movies, whose teenage sons and daughters ape the projects, whose suburbs are more and more penetrated by the fashions and features of city life? You, too, suffer with car alarms. You, too, have the neighbor with the lemon whose engine turns over and over like it has the croup. You have this neighbor, and the neighbor who plays his stereo too loud, and maybe you or your neighbor has a teenage son with access to the car keys, the car stereo, Nas, Tupac. These are your sounds, too. Ours are just louder, and more intimate.

Oh, the shame of cities, if they were to be unmasked as nothing more than overgrown suburbs, like teenagers who never left their parents’ basements! If all the exoticism that drew small-towners to their bright lights were revealed to be only a difference in degree! Bigger! Taller! Faster! Is that all that makes a city a city? Or does any organism induced to grow, and to grow, and to grow, change constitutionally, radically? Do new species arise from combination, like new particles forced into existence by the speed and intensity of their parents’ collisions? Then the city would be more than the sum of its recognizable sounds, as the proximity of sound to sound would create a genuinely new organism which a catalogue of city-myth sounds could only hint at. Though writing compels me to catalogue sounds as if they happened in series, your task, reader, is to square them, so that they appear, as they do to my consciousness, as a single, dissonant chord.F

*

When it’s summer, or late spring, or early fall, or a mild day in late fall—or a cold day in late spring with a few moments of sunshine in the late afternoon—the ice cream trucks begin their relentless assault. They start at noon, or just after noon, and can carry on, wave after wave, until ten, sometimes eleven at night. Nothing else in the neighborhood, not car alarms, not firecrackers, not domestic disputes carried out on stoops, can compare to their outrageous violence against peace and sanity. They are—they must be—the fiendish invention of a totalitarian mind. Their numbers are beyond reckoning; they must have hives hidden across the city; I have dreamed of torching these nests, finding their queen. Our neighbor simply call them the enemy. On hot nights she is tempted; she takes a soldier’s pride in resisting.

They lure their prey with … songs: “The Entertainer,” “Pop Goes the Weasel” (which ends with a gratuitous and blood-chilling “Hello!”), and “It’s a Grand Old Flag.” The songs all have the same flutey, Jack-in-the-box timbre, and this together with the slow revolution of the trucks’ wheels suggest the steady turning of a crank by a giant, invisible, malevolent child. At the height of summer, when the trucks swarm like gnats, just as one sinister, inane, interminable song begins to doppler off toward Knickerbocker Avenue, another will be just beginning at the top of the street. And as one truck is replaced by the next, one song rises in pitch while the other falls, one melody becomes entangled in the next: an ice-cream avant-garde.

I’ve heard trucks drive by with loudspeakers booming for this or that local politico, and I’ve heard the police van loudspeaker asking residents to turn over any information anyone might have connected with the shooting at S&M Children’s Wear (real name, actual store). The difference is that the ice cream trucks stop. We have a fire hydrant in front of our building; the drivers pull over there. The loudspeakers are just above the level of the awning, just below the level of our windows. In the few seconds between melody loops, I hear the freezer motors pumping hot air into the hot evening.

I’ve often wondered how the drivers bear it, if they’re all lobotomized, drooling, or just deaf, trapped all day in these rolling sweatshops, test subjects of top-secret psy-ops against working-class communities. For the disparity between rich and poor neighborhoods can be summed up this way: a block or so after passing an ice cream truck on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, I realized the loudspeaker was turned off. Then one day last fall I was walking home in a thunderstorm, and an ice-cream truck passed me going in the opposite direction. It was going much faster than its normal predatory speed, its Slow! Children speed. And instead of ice-cream music, there was salsa blaring inside the truck. (Why didn’t he play thatover the speakers?) And the driver—this is the most important thing—the driver had one arm extended, as to an imaginary band, and was singing along with the music at the top of his lungs. He was no longer an ice-cream vendor, he was Ismael Rivera, he was Hector Lavoe. I thought he must welcome the rain the way I used to when I lifeguarded at my local pool. When it stormed, we would don garbage bags and slide down the places where the surrounding hills had turned into sluices.

When evening falls in Bushwick, car alarms begin to compete with the ice cream trucks for sonic realty. This is another wholly novel combination, a rich cacophony of which the city, and only the city, is capable; a sonic landscape that appears most fully in the evenings, like craters on the moon do on a clear night. The car alarms go off for one of two reasons (neither, needless to say, having anything to do with theft): (1) the kids who play football in the street hit one of the cars; or (2) somebody cruises by with the stereo cranked. The second is the more common; I imagine the drivers as bombardiers, alarm after alarm exploding to life behind them as one shrieking target after another goes up. Three, four, sometimes five in a block; our windows rattle and buzz, boom, boom, boom, but our building stays standing. And then one after another the alarms turn off, though never in the same order they were tripped. I would call it the only real test of a car stereo … except that most of the alarms are so sensitive I could trip them by farting ten feet away. I’ve learned half the hit songs of the past two years listening to Hot 97 doppler down my block. Melodically, there isn’t much difference between 50 Cent and, say, “Pop Goes the Weasel”; and I can already imagine a day when he replaces “It’s a Grand Old Flag” on those loudspeakers. But it’s the bass that trips alarms and rattles windows, that finds the frequency at which the neighborhood vibrates, revealing its armature to us bystanders—hence, perhaps, that fleeting sense of vulnerability that always accompanies their passing.G

There’s also a hospital two blocks north, so once or twice a night an ambulance, and sometimes a fire truck, goes gangbusters down our street, siren on, horn blaring. And some nights the traffic gets backed up all the way to Irving, because the ice cream truck hasn’t quite pulled over far enough for the asshole in his SUV to get around it. Or maybe a gypsy-cab driver has arrived to take someone to the airport; they never pull over far enough, and they never get out of their sedans; they’ll lay on their horns for ten or fifteen seconds at a stretch, like their car has been front-ended. And then, of course, an ambulance will arrive. So you have the gypsy-cab driver’s horn and the SUV’s horn and the horns of all the traffic backed up to Irving, and then the ambulance’s siren and the fire truck’s siren; and when someone finally moves, here come the ice-cream trucks, and Hot 97 tripping alarm after alarm after alarm …. Good night, good night!

And the people? They’re here; they never stopped talking. They’re the ones sitting behind the wheels, laying on their horns, setting off alarms. Why shouldn’t they cruise the streets, their bodies pressed together inside the Church of General Motors, heads bobbing? Why should anyone have peace and quiet when they don’t? Later, they’ll stay on their stoops until two or three in the morning, shouting, laughing, arguing, as if they feared silence were a void that might swallow them. Only cities produce such voids, such silences that the noise rushes to fill—not actual but epistemological silences. Only in cities, among millions, could people fear silence as an emptiness, their own blood-sound masked from them, masked so long that it’s forgotten; and hence their understanding of themselves as beings apart from the great puling, pulsing mass of the city, is forgotten, too. Or maybe the opposite is true: a horror at their own blood-sound, at recognizing their separation from and powerlessness in the face of the city. A bit of krill in the maw of a behemoth—and so they shout, shout not to challenge but to fill, or at least mask, that silence, that gap—to become one with the beast of the city that threatens to swallow them.H

And so they shout, Fuck fuck fuck fuck fuck, fuck you, nigga, fuck you nigga, the rest in Spanish. Even in the quietest moments they speak to one another as if they needed to be heard over the roar of a passing train. Broken bottles, firecrackers, radios, motorized scooters; the couples fight ruthlessly on, the teenagers giggle and shout, “Ah, shit!” and sometimes in the early early morning there is an episode of drunken bravado among young men. They’ll be up again with the birds,I at least some of them will, yelling up at the windows across the street (because only UPS and the Jehovah’s Witnesses use the buzzers), waiting for someone to come and lean over the sill (ours seems to be one of the few buildings with screens) so that they can carry on a conversation between two or three stories. I’ve seen people converse between the same story of adjacent buildings, and even across the street, between windows of facing buildings. We have our neighborhood crier, too; just the other day, he shouted, “Wake up wake up wake up!” beneath a nearby window, like he was calling to his lover to elope. Then he called out, sarcastically, “I said, Good morning!” (And then a child’s voice echoed his: “Wake up wake up wake up!”)

Sometimes I feel like the people of my neighborhood are on the point of being evicted from their own voices by the noise. And yet, the neighborhood lives in their voices. And not just in the profanity and bravado. Over the last thirty years, but particularly since the crack boom of Reagan’s ‘80s, contemporary culture has succeeded in doing to the “inner city” what high-school English has done to poor Jonathan Edwards. The children of the boroughs are left to hang over the flaming pit of God’s wrath, like Edwards’ sinner-spiders. Forgotten is the youthful Edwards’ fascination with spiders and spider-webs as evidence of a meticulous and beautiful divinity, or his desire for the “sweetness” of a quasi-erotic union with Christ. So little of the sweetness of the “inner city” finds a place in our national mythology anymore. Here are two exceptions: the squeals of children running through the open hydrants in the middle of July, the jet of water striking the cars across the street (without the awning, we might see an older boy straddling the hydrant, a two-foot crescent wrench held in his hands); and the shouts of teenagers playing football in the early evening, partly because the one miserable park in our neighborhood has been closed for more than a year, partly because they would play nowhere else. Maybe because these are the sounds of poor neighborhoods historically and citywide, they have translated to our consciousness through the movie screen. But there is so much more. In the fairy-tale quality of the people conversing between buildings, as if they lived in shoes; in the voice of the ice-cream-vendor-cum-Hector Lavoe barreling down Knickerbocker in a thunderstorm; in the voice of the female worshipper in the Pentecostal church belting our her raucous love for Jesus;† in the clack of the dominos striking a folding table, and the swears of the old men (and women) gathered around with their berets and cigars, their canes leaning up against the metal fence around the trash cans and the grandkids’ toys too big to fit in the apartment. One of our neighbors has a little dog named Princess (I’ve never seen her, but only little dogs are given such names), and every time the dog goes yap yap yapping down the street, their little girl follows it, yelling, “Princess! Princess!” like she’s looking for an enchanted castle. She’s sure she has seen it, here, in this neighborhood. And every night, around ten-thirty or eleven, sure as church bells, somebody drives by with a car horn that plays the first half of the melody of “La cucaracha.” I imagine La cucaracha is in love with a girl who lives somewhere on our street, and she leans out her window at night waiting for him to give a signal, like a queen waiting for those knights of old to lance her garland. Listening to all this, I sometimes get the sense that the world ends and begins at the beginning and end of our street.

I know that Princess is little enough to be eaten by the rats I hear scampering around inside the garbage cans, and that La cucaracha may be fingering a gun. I know that the kids playing football are some of the same ones who tear each other apart on the stoops in the middle of the night, or who press our buzzer five, six times (it makes a high, loud, tickling noise, like a robot mariachi), who we can hear laughing when we press the LISTEN button. I know that when I stop looking, I’m more prone to fantasize, and that I’m in danger of romanticizing poverty with all my castles and garlands. But at least my ear does not immediately reject our street’s often grim exterior the way my eye does. Of the two organs, it’s the more naïve, the more playful. It’s the one most adept at taking an ell from an inch, as Henry James once said. And who’s to say my fantasies don’t speak another truth about this neighborhood, about its hopes and fears and disillusionments and love of life, a truth not accessible to my eyes?

The Back Window

New York City is an amalgam of discrete worlds whose edges touch but whose inhabitants seldom range beyond them. Each world disbelieves in the adjacent ones. I remember feeling this, without really understanding it, many years ago, standing at 110th Street and looking north into Harlem. The people there—the ones sitting on their stoops and crossing streets and driving cars—seemed like denizens of another world, and I couldn’t help but think of Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles, where Martian and Earthling wave their hands through the place where the other’s body should be, and each declares the other the ghost. But worlds come in different shapes and sizes, and not all the boundary lines are evident, or simple, or permanent, or tangible. I walk home along my street every night, but would not walk home on Stockholm, one block over. Knickerbocker is not the same place in the daytime, with hundreds of families bovining between dollar stores and the traffic bumper to bumper, as it is at night, when the grates are all down, the trash rolls around like tumbleweeds, and the infrequent cars all seem to have been sent on unfriendly missions. And of course I can walk through Harlem and not be in Harlem, or of Harlem. New Yorkers carry their worlds around with them, like I do now, in Bushwick.

But for New Yorkers who have their roots in the city, these boundaries are reinforced by a strong sense of territoriality. Once on a shuttle bus (for subway repairs) I heard three teenagers from the neighborhood talking about how they couldn’t take the subway to Queens because they’d get lost. New Yorkers are like dogs chained up in backyards, intimating that there is a world beyond the fence because of the other dogs they can hear barking, but reconciled to the leash and the fence as facts of their existence. What lies beyond the fence exists only as blurts of noise.J

If the structure of the city is predicated upon these intimate yet eternally sundered worlds, then it’s little wonder that the back and front of my building seem to occupy radically different coordinates in space-time, so that the sounds I hear at the front of the building are wholly distinct from the ones I hear at the back. If the front window is the tympanum for everything mechanical and human that invades our personal space (the boundaries of which, in cities, are difficult to define)—ice cream truck, car alarm and car horn, fire truck and ambulance, loud music, loud conversation, argument, sport—the back window hears none of this. Instead, the back window seems to open out on some weird, nostalgic space, as if by crossing the floorthrough we were to step back decades in time; as if the city itself were just a façade banged up over a rural/small-town past which, but for constant vigilance, always threatens to irrupt back into the industrial landscape. This is all the more remarkable for the general lack of vegetation: our backyard is a bleak little concrete lot to which we do not have access; beyond the fence and the telephone poles are the buildings with their backs to ours, like duellists: one half-erected, one boarded up, one occupied. The “yard” behind the unfinished building is a mound of rubble and trash that couldn’t squirt out a blade of grass to save its life. The adjacent yards, with their few scraggly bushes and chain-link fences, are hardly better. But for all their ugliness, the buildings do mute the front-window sounds we would receive from Stockholm. Hidden from the streets, cut off from the city proper, these backyards become their own worlds, with their own narratives and their own sonic textures. And this makes sense, because generally we are by the back window late at night, when the things we barely hear in the daytime find their voice, speak out loud.K These are the sounds of the city’s dreams, when it remembers and reconfigures its pasts. The farm and small town were the land’s previous tenants; progress can never entirely evict them.

Old industrial neighborhoods like this one are particularly good at hiding spaces that seem to arise out of a distant past; or perhaps such spaces are simply more surprising because of the industrial façades that hide them. Walk down a row of small businesses in a mixed (industrial-residential) neighborhood—body shops, ironworks—and all of the sudden there will be a break in the row of garages, and you will glimpse the corner of a decrepit wood-frame house standing in the lot behind—maybe the house where the owner’s family lives—otherwise invisible from the street. The whole neighborhood is honeycombed in this way, as if, could you peel back the rough, toxic gilding, you would find something that looks like small-town America, all this soft wood at the heart of iron. Sometimes, I expect to look out the back window and see a white picket fence, rolling green hills, the nub of a silo. And if I can’t always find those wood-frame houses, I can still hear the sounds we associate with them.L

Here is another example: the wind sometimes picks up and slaps a wire running down the back of our building against the window. We have no idea what the wire is for, or any of the wires, for that matter, that run in a clump along the back fence, fastened, like the neighbor’s clothesline, to a short electrical tower at the limit of the property. We’re surrounded by such wires, and so entirely lost in the jungle of the visible that we never think to question what their function is. What does that wire do? Where does it go? If it does nothing, why hasn’t somebody torn it down? I imagine that half of the technological infrastructure of this city is obsolete, but no one has bothered to dismantle it. Instead, this skeleton of dead industry remains, like the wood-frame houses remain. The city is thus a museum of itself: it retains the shape it had a century before, is modernized in the interstices. Meanwhile, its inhabitants live and travel in a web of signs whose contexts have long since disappeared, inscrutable messages from a long-dead society. They echo, like that gargantuan rush of blood, in the noise of the city’s background radiation.

One night, we heard a loud ringing on the fire escape, and we looked out to see two or three kids picking up stones in the empty lot—this was before the new building started going up; at the time of this writing the lot had been vacant for almost a year—standing on top of the Caterpillar, trying to break our windows. Is the boredom of the boroughs any different from the boredom of, say, small-town Kansas? And do the kids respond differently? Don’t their grandmothers all live in the country, in the D.R. or Puerto Rico? And when my partner played Crazy White Lady out the back window and the kids scrambled, was she any different from the lady in the run-down, gabled house who, at the end of the movie, is discovered by one of those kids—the one who gets to grow up—to have been jilted, or bereaved, to be full of wisdom, and to bake great cookies?

And does the elevated train—which for some reason I can only hear out the back window, at night, even though it’s closer to the front—does it sound any different from the trains rolling through the countryside, the trains I’ve ridden from New York to New Orleans, from New Orleans to Tucson, from Salt Lake City to New York City, from Chicago to Longview, Texas? Aren’t they the same trains against which children test their wills, trains they dream about and imagine leaving on to get from there to here, from country to city? Maybe because the 99 cent stores on Knickerbocker pull down their grates, the street becomes a conduit for the sound. Because I only hear it at night (mind you, the train has been to us a lullaby ever since we lived half a block from the elevated N in Long Island City); and though I know it’s the M, I sometimes imagine it’s another train, a freight train carrying shipping containers across the heartland. Maybe there’s another track nearby for freight trains that I haven’t come across. But that seems unlikely; I’ve criss-crossed this neighborhood walking in every direction. I’ve since come to the conclusion that I will never see such a train in the daytime, I will only hear it at night. The only other evidence I have of this crypto-locomotive is the old tracks, laid bare like dinosaur bones in places where the asphalt has worn down to cobblestone. You might follow a set of these ghost rails for a block before they run straight into a three-story building, or a closed garage door.

Not surprisingly, this band of rural America folded into the fabric of the city is a veritable old MacDonald’s farm of animal-sounds. The most important is the rooster; indeed, that might be the essential sound of the back window, the one from which all other ideas of the city’s wild, rural past arise. It’s probably a fighting bird. All the same, it crows every morning. And this is a most surreal and lovely thing to hear in the early mornings in Brooklyn.§

By itself the rooster isn’t enough to wake us; maybe the white picket fence upon which it stands has receded too far into the city’s past, into the nooks of its echoing backyards. But the rooster sets off the first of two dogs chained up in separate yards; and then the first dog sets off the second, distinguishable from the first by the pattern, pitch, and stress of its bark. This dog goes on barking long after the rooster and the first dog have given up. I’ve never seen these animals; the only visible dog is the one let out onto the third-floor fire escape of the building beside the vacant lot, and that dog is as silent as a beaten child.

Walking home, I sometimes see stray cats slinking between the cars, giving wide berth to the garbage cans where we hear rats forage. But these cats are cowed, voiceless; in the backyards, at night, they fight with other cats, or with the rats—the preternatural meow, the lid of a garbage can upset—and set the dogs barking again.

There is one animal in our neighborhood that we have not identified. Like the rooster, we hear it at daybreak, but also sometimes at sunset. Like the rooster, it’s too quiet, or maybe too distant, to wake us. It makes a sound somewhere between a moo and a bray. Every farm needs a beast of burden, and this seemed like the capstone of an act of collective nostalgia for this bit of Jeffersonian America squirreled into backyard Brooklyn, the complement of the semirural domesticity of rooster, dog, and cat. But over time, we grew less sure about the beast-of-burden theory. And the longer we were unsure, the more we came to believe that this sound was the sound of something in pain. And because we could never pinpoint the animal that made it, the sound evolved to signify agony in the abstract: all the hunger and hurt of city life that had accumulated over the course of a day, bottled and released just before nightfall, and then again, in the morning, the sounds of the previous night.F

I never ventured to go out looking for this thing-in-agony, or even called 311, like I did when I heard what I thought was an injured dog. That time, I even got my shoes on before it stopped. But this sound, whatever it is, it’s too far away—maybe not even in our neighborhood. The labyrinth of buildings probably distorts its direction and quality: I’d never find it; it’s quite possible that I’ve misinterpreted it. And before I know it, the sound has disappeared, just as I think I’m arriving at the salve of conscience, the pot of gold. Is this monstrous sound the sound of what the city makes us, that the reason we don’t put on our shoes and go looking is because we’re afraid to step up to that mirror? It is it, not us, just another sound the city makes, its breath and circulation, like the gunshots and sirens and arguments. As to why the siren, why the gunshots, we don’t concern ourselves. We listen, watch. Write. Just yesterday a man sat down in the rightmost lane of Broadway at 138th Street. He sat closer to the middle lane than to the curb; the cabs honked and swerved to avoid him. He was shouting and waving and his arms were covered with sores. This is almost any yesterday.

This sound-of-agony is really just the other side of the coin of the farm, a lament for its passing, for all passings, and the pangs of a city in constant, ruthless rebirth.D We would hear the beast in the rooster, and vice-versa, if we could just properly calibrate our ears. It’s no wonder these are night-sounds and twilight-sounds; in the day, the city is alive with the sound of self-renovation, enthralled by its own ever-evolving modernity: ten hammers going at once and the grind of table-saws, men working to fill the gap on Stockholm with “luxury two-bedroom apartments” like ours. On some blocks a subway stop closer to Manhattan, five or six buildings in a row have been gutted: the usual slow bleed of evicted families carting their possessions to the next barrio of hope, while a few manage to duck the wrecking ball, and another few claw their way out beyond the semi-urban ring that has replaced the inner city. Then, like a crocus, the first Starbucks will push its way up out of the hard ground, and some multinational corporation or sports team will throw down a mat of wood-chips and a plastic slide and call it a playground. Eventually, from this unpromising chrysalis, a gentrified fantasyland will emerge. And then the wrecking ball will move on, leaving the new neighborhood to live on for years, perhaps decades, before recognizing that the economy that birthed and reared it no longer exists, perhaps never existed. And then, like Poe’s M. Valdemar, it will decay with the same fantastic and violent suddenness that marked its rise.

What language reveals about subjectivity is true of cities, and truest of New York: a present is never quite present because it is always already being enfolded into the yet-more-modern. Yet, as workers scramble to fill the gaps produced by the most recent guttings and demolitions, so they will re-seal the backyard worlds of pre-modern echoes, the voices of these hidden pasts, behind new facades; a forest within a farm within a town within a city within a city within a city will once again grow and multiply among the rubble and the weeds, the ghosts we hear in our backyards, the skeleton of industry on which the information-age city multiplies. So long as these tomblike spaces are opened, however, the past sounds and sounds-of-passing will seethe together with the sounds of modernity and modernization: the hammer and the table-saw, the rooster and the beast. It’s just easier to hear the latter late at night or early in the morning, when the saws have dulled to quiet, when the wind is right, coming as if from a great distance, or caught in the corners of our eyes, like the ubiquitous, miraculous bouquets in Jean Genet’s Miracle of the Rose.

There’s a girl who stands in the rubble and trash behind one of the buildings on Stockholm, earphones on, singing the latest pop songs at the top of her lungs, and choreographing a video in which she is the star. There’s the occasional loud barbecue, occasionally hosted by the downstairs neighbors, who sit out back and talk on their cell phones, and their voices rise with the smoke from their cigarettes. On the nights the neighbors upstairs were robbed, there must have been the pitter-patter of thieves’ shoes like pebbles on our fire escape. And once, in the dead of night, long after the last firecracker had popped, I woke up to a Boom, followed by a series of booms, maybe one per second: Boom. Boom. Boom. Boom. Just like that. Too evenly spaced. I didn’t hear shouts or sirens, but then again it had come from far away. Boom. What the economy was supposed to be doing thanks to the dot-commies in dotcomlandia. The quakes in the Bay Area rattled the windows of Giuliani’s New York: shutting down Fresh Kills and using the scowls to ship the homeless out of sight of commuters or tourists, christening Riker’s Island our sixth borough—the best kind, since no one can vote and the borough president’s a warden …. And then BOOM, the towers came down. Echoes like a million gunshots, in the night and in the early early morning. Sometimes I think it’s the sound of Giuliani coming back to haunt us, all rattling chains and 9-1-1. Two years later came the blackout, and there was near-absolute silence in my neighborhood that night: the silence of waiting for another BOOM. What we didn’t hear was that everyone else was waiting for the boom, too, and that silence was the sound of all of us together, waiting.

Inside

Just as every block has an exterior sonic identity, a combination of block-specific and neighborhood- (or even city-) wide sounds that enter through the back and front windows or exterior walls, and which vary depending on the vantage point of the perceiver; so each individual building has an interior sonic identity, composed of the amalgam of noises made in one part of the the edifice—the automatic functions of the building, the natural forces acting upon it, the sounds made by the tenants, their pets, and their appliances—and heard in another, measured, as always, over a given length of time. The fact that our building is so small, and the interior walls are so thin, gives me a false sense of completeness about my perception—the sense that I am a “transparent ear” (“I am nothing; I hear all”). I am actually limited in several important ways: by the location of the apartment (second-floor floor-through), by the arrangement and selection of its rooms (bedroom in the rear), and by the difficulty of where and whether to include myself, whose presence, negligible among the sounds of the block or neighborhood, now becomes significant.

As with the mix of Spanish and English we hear out the front window, there is a linguistic dimension to the sonic profile of our building which, when we first moved in, and in the context of the neighborhood as a whole, suggested neatly-inverted geological strata: young, hip Euro-Americans lived on the first floor; a Hispanic couple with a baby lived next door to us on the second floor; and an old Italian couple lived with their grown son on the top floor. Unfortunately, this schematic, representing three waves of migrants to Bushwick, is muddled once we’re forced to include the Indian woman who lived upstairs, next door to the Italians, and who had a white boyfriend, who lived there off and on and parked his motorcycle in front of the fire hydrant. And then the Hispanic couple moved out, and young, hip white people—a punk rocker and a political activist—moved in next door, as per the general trend. And then the Indian woman moved out and two young Hispanic men moved into their apartment. So much for geology. (I should note that I haven’t included myself, either, since I, too, would muddle it.)

The Spanish-speaking couple argued from opposite ends of the apartment. The old couple yell at each other in Italian, though not belligerently, or only when what we presume are their grandkids pay a visit. They could be the son’s kids from an earlier marriage, though that seems unlikely. He is a perfect recluse. His manner is halting, and his glasses make his eyes appear enormous. He fiddles with the garbage and recycling in front of our building for what seems like hours, sometimes removing a stray item from one bag and putting it into another. Sometimes, when I think I hear a rat in the trash, it’s really him. And sometimes I see him coming up out of the basement, although none of us is supposed to have a key. I don’t ask. Anyway, the grandkids are boys, fat, maybe twelve; they clomp clomp clomp up and down the stairs, like they’re trying to make as much noise as possible, and they always jump the last few steps, like I do. They also yell, and then the recluse or their mother will yell at them to be quiet, and they’ll yell back up at her that they will be quiet. This all in English. The new Hispanic men and the ladies they bring home at night are more cheerful, and the Anglos across the hall are also cheerful, and occasionally drunken, as they carry on conversations with each other from opposite ends of the floor-through. He is a punk rocker; we suspect he lives in an entirely different sonic dimension from the rest of us.

When the doors close, the voices are muffled by walls, as is the case with almost all the noises we hear inside the building. We know the language being spoken more from the cadences than the words, and again we have that sense of being the focal point in a field of sounds, a sense augmented by the thin walls, which act more like membranes than barriers. It is this general radiation of voices, and not actual narratives or individual signs carried on their currents, that make the city: a sea, formed of all the registers of human voices blended into one another, in which we float, half-submerged.F There is another, perhaps a greater, intimacy in them, too, than in the confessions about sex and family dysfunction whispered into our ears or overheard in cafes, because this murmur of the mass of humanity is apprehended less consciously. There is an erotic life to the city that is this constant friction of vibrations of people against each other, and that is the helpless and constant penetration of others’ lives into your own, of your life into theirs.M Our walls are like windows of semitransparent bricks, silhouettes move mysteriously and seductively behind them. I am awash in my neighbors’ muted sounds, just as they are awash, perhaps, in mine. I didn’t choose to have them meddling in my life, just as they didn’t choose to have me meddling in theirs. The people around me are my secret sharers; yet, if I saw them on the street, I might not recognize them, and they might not recognize me.

An example: I know the people who live in the apartment upstairs walk around in their shoes. From the whine of the pipes, when our neighbors use their shower and toilet, and generally, from the sounds of their coming and going, we know what hours they keep. Their alarms wake us up, as if they were sleeping beside us, with us; the punk rocker, whose bedroom is adjacent to ours, can hit his SNOOZE button for an hour before finally shutting off the alarm. My brother-in-law does the same thing; I know because I lived at my partner’s mother’s house for three months, and he had the room directly below mine. But the punk rocker is hardly my brother-in-law; in fact, for the first three months after he moved in, I never laid eyes on him. One of the Indian women upstairs had a clock-radio that went off every nine minutes, Led Zeppelin or The Doors, two or three different songs (after all, even that magnum opus “Stairway to Heaven” only lasts seven minutes and fifteen seconds). And when the political activist is out of town, or gets lucky, she doesn’t turn off her alarm, so it might go off all morning through the wall, loud enough that, the first time it happened, I thought it might be the fire alarm, and so I went out to investigate, rang the doorbell and knocked—I thought she might have a cat, you see, I had heard cat-sounds, that clumsy sound cats make jumping down off of something tall. Where was the punk rocker? On tour? And if it took him an hour to wake up to his alarm, how would ringing the doorbell make any difference? Anyway, had it not been for that alarm we might never have left a note on the door to please turn off your alarm when you’re not home, might have gone another three months without meeting them, without ever inviting them to dinner, without ever sitting down to dinner in our apartment and talking, imagine, about sounds.

There is thus an intimacy that the walls between us seem to enhance rather than impede, the same kind that must develop between prisoners in adjacent cells. While some of the qualities we associate with intimacy are lost (I have not yet seen the new people upstairs, except through the peephole, from behind), others, which go well beyond that veneer New Yorkers call intimacy, are magnified. It must be the atomic quality of city life that causes this surrogate intimacy to develop (I have not yet seen the new people upstairs, except through the peephole, from behind). What’s more, I suspect the absence of the first, commonly understood, or “natural” intimacy intensifies the second to the point of pathology. Or maybe it only seems pathological, because it is the particular intimacy of the city, and we are not city dwellers, we humans, not yet. It is the powerful aphrodisiac of anonymity, where, in the absence of any other signifier, the body becomes all.

And this is apt, since what we overhear most often is the sound of people fucking. I might hear somone fucking for six months to a year before meeting them face to face, and I have to refrain from saying, “You know, from the noises you make when you’re fucking, I imagined you entirely different.” Already devoid of all but the most obvious significance, these sounds of intercourse—the ersatz bedsprings;** the gasps, grunts, groans, yelps, shouts, and sighs; the occasional forays into language in the form of shouted exclamations and demands—reveal how our possible responses to “overhearing” fall into two diametrically opposed categories. By and large, as meaning is evacuated (as it must be in this sea of unintelligible sounds), emotional content, as if in a rush to fill the meaning-vacuum, is enhanced.

But then one night, while I was grading papers in the living room, I heard the political activist fucking her boyfriend, which amounted to nothing more than a few squeaking bedsprings (yes, bedsprings) and a gasp. A heartfelt gasp, possibly, but with gasps it’s difficult to tell. Hardly a primal gush of emotion, a window into my neighbor’s soul. Instead, I was left trying to decipher its meaning. And this problem of meaning became even more poignant in hindsight. Because, you see, the political activist’s boyfriend later started stalking her, and she had to show everyone in the building his picture so that they wouldn’t let him in. After he left New York he violated his parole and started back here with a gun, but was apprehended en route, somewhere in Pennsylvania, I think. Was that gasp a gasp of foreshadowed humiliation? I now believe that, had I been able to interpret that gasp correctly, I could have foreseen my neighbor’s whole calamity with her boyfriend.

The Indian women upstairs I never heard fucking, but the political activist said she heard them having sex all the time, and loud and raucous sex at that, to the point that, over dinner with us, and right next to the open window of the air shaft, she remarked that they were so loud that half the time she figured they were fucking in the stairwell. I didn’t hear the women’s shoes, so I guessed they weren’t home. But I always wondered if they heard her say that. Because later, when their apartment was robbed, and the political activist went upstairs to sympathize, they shut the door in her face. That was the night we heard the cops’ shoes in the stairwell, loud as gunshots, and their cop radios, and they giggled like they were stoned. Between the girls and the cops treading back and forth in their shoes it sounded like a stampede. Plus the robbery happened while my parents were visiting, and to this day my parents still believe the cops’ shoes were the shoes of the women who lived upstairs.

But I was talking about fucking. How come the political activist could hear the Indian women fucking when they lived directly above us? I never heard them fucking, and I would have liked to, if only for the sake of completeness, excluding the old Italian couple, who can’t possibly fuck anymore, and their son, who I try not to imagine fucking at all. But those girls were real nightcrawlers, their schedules more likely matched the political activist’s.†† Moreover, this third-floor fucking must have occurred in the front part of the apartment, and, as I mentioned, our bedroom is in the back. When the beauty parlor beneath the front part of our apartment got robbed, we slept right through the alarm. That the political activist, who lived in the front room, could hear the women upstairs fucking, even though their apartment is directly above ours, supports two related assertions: (1) in small buildings, adjacent floors are more “intimate” with each other than the front and back of the same floor-through apartment, with the surrounding apartments functioning as auditoriums; and a corollary, (2) one is less “intimate” with one’s roommate in a floor-through (that is, the person who sleeps in the other room of the same apartment) than one is with ones’ neighbors living above or beside, even those to whom one has never been formally introduced.

The punk rocker is case in point; as I mentioned, our bedroom shares a wall with his. He’s often away on tour; but when he’s home, watch out. His then-girlfriend (and current wife) is a dominatrix—a professional title, I think, as well as a personal preference—and now and again, between tours, they wake up my partner and I with an unruly combination of surf-punk music and fucking. The wall is a hymen; their ecstacy punctures it. And this is always in the wee hours, the desperate hours, when our defenses are down … and close enough that, if she or he reached out to grab the headboard (except we don’t have headboards), and the wall disappeared, they would grab our hair, our wrists. We become the passive half of a foursome.

But there is also the pleasure of nostalgia for our own sexual pasts, and our sexual subjunctives. Punk rockers are particularly helpful here, since they still listen to music on cassette or vinyl—I think it’s part of their image—and so it’s legitimate to measure the time they spend fucking by album sides. According to this system, and after adjusting for the fact that punk albums are about half the length of most pop albums, I placed him, incorrectly, in his early twenties. I wonder if the old Italian couple upstairs could hear them, too. I imagine them listening in concert with their son, like in one of those Rockwellian images of the nuclear family gathered around a tombstone-shaped radio.

On one remarkable night we were awakened at two or three in the morning; the dominatrix was engaged in some lascivious moaning, which turned into brief, high shouts as the punk rocker built toward what turned out to be one of several climaxes, the report of the bedframe as it struck the wall or the floor, ka-chunk ka-chunk ka-chunk. But the remarkable part was that, for a while, there was a sound like one of them was collapsing onto the floor, or being dropped onto the floor, or jumping off the bureau onto the floor, or just dumping a whole bunch of shit onto the floor. This sound was repeated every ten to fifteen seconds, and every repetition was followed by a guttural grunt on the dominatrix’s part. Lying there, I couldn’t help but think of Burke’s definition of the sublime in Milton: words tumble upon the reader in such a way that, rather than appealing to the imagination, they strike directly at the emotions. Try as I might, I couldn’t imagine how those sounds were being produced. None of the elaborate machinery I concocted in my brain—pulleys and swings and mechanical massagers and penetrators worthy of the most perversely fervid eighteenth-century mind—none of it sufficed. And it couldn’t possibly fit in that tiny room the punk rocker lived in anyway; nor could he have afforded such a machine on his certainly meager earnings opening for opening bands’ opening bands; nor could the dominatrix possibly have sufficient capital to invest in the means of production I envisioned. Anyway, I had a hard-on. My partner woke up briefly, said, “Fuck me, punk rock boy!” and fell back asleep. Or did she lie there, awake, aroused, like me?

I’ve imagined a story where the protagonist, a middle-aged recluse like the son upstairs, hears a couple in the apartment next door having sex. The couple is new to the building; he has lived there his whole life. He has never met them or seen them (“except through the peephole, from behind”); he believes they deliberately avoid him. The noise wakes him, keeps him up. He imagines himself as a liquid, filling up the space of his apartment, so that his boundaries and the apartment’s boundaries are contiguous. He is fully contained by his space; why is the same not true of his neighbors? Why must they nightly violate his space, his body? So he grumbles at breakfast, groggy, he complains at the nearby park to his few friends, who tease him. He is secretly aroused. He grows to expect the sound of the couple’s lovemaking. He participates in it vicariously. Then, near the end of the story, he confronts the guilty couple. He might ring their bell; he might run into them in the hallway, outside their apartment, at last; he might gather the nerve to invite them to dinner, where his own conversation is drawn, helplessly, toward the forbidden subject. He would say something, dramatic, ambiguous, totally ridiculous, through which his participation in the couple’s sexual life would be revealed … or, at least, he would fear that it had been revealed. Or, he might record the sound of the couple having sex, and then, the following night, move his small stereo so that the speakers abut the offending wall, and play the recording at full volume. But in the following moments he would become convinced that it is not the sound of the couple’s lovemaking, but himself masturbating. So, rather than punishing the neighbors for keeping him awake, he makes a spectacle of himself; and at the moment he tries to assert his power—deliberately penetrates the boundaries of their apartment/body—he humiliates himself most abjectly. One more thing: listening to that recording, listening to himself, he might come to recognize something about himself, something ugly, something violent in the sound of his pleasure. Maybe he already noticed this in the sound of their lovemaking; maybe part of his obsession was that he imagined interposing himself as her chivalric avenger. Whatever the case, at the end he understands that what he believed about the other was actually about himself.

The first fear is the fear that every sound is simply a reflection of you, that the walls are mirrors, that you are alone, inviolate and impenetrable in a city of millions. You may feign annoyance, but your sanity and your sense of self depend upon the constant penetration of others’ lives into your own. The second fear is that, for all your supposed voyeurism, or eavesdropping, you are helpless but to reveal secrets about yourself. Chief among them is your eavesdropping, because around it all of your other secrets orbit. You crave these revelations in spite of your fear: this quid pro quo the city demands for all it has already revealed to you. Of course, the secrets most in danger of being revealed are those you have hidden from yourself. In the city, there can be no self-knowledge without prior public revelation (though it may not be understood as such at the time). The city becomes the bearer of these unknown secrets, the as-yet-unplumbed core of your being (inner city, indeed). Knowing the city hence becomes a precondition for knowing yourself. In the standard formulation of the urban uncanny, the city is particularly self-alienating. Here, however, those things from which you have estranged yourself are not simply packed away in some mental cellar, awaiting the proper stimulus to surface. They have been picked up by the stray antennae next door, beamed down the cable crossing your back window, and on through all those seemingly useless wires that make up the circulation of your neighborhood. If they return, when they return, they will be as The City, the great Other, the amalgam of ten million sweating, groaning bodies who have been listening to you, too, who know you more intimately than you do, who have abolished secrecy as such. And then The City will say: I know you! I have your secret, your soul! You are not alone in this; you are entirely alone in this, and so you will remain, until the walls come down and you plunge into the erotic spectacle of yourself.

You expect to hear the essence, the distillate, the monstrous secret of that thing behind the wall. But it is your own desire you listen to, just like it is for my protagonist. Maybe that’s why there is never anything particularly revealing in the noises that I hear—at least, not the revelation I expect. And maybe that’s why, unlike the noises from outside the building, which are meant to enter our much-contested personal space, the meaning of these indiscreet noises remains less clear. As voyeurs, we want to believe they are the sounds of people’s most private moments. But if people are so reckless, sowing their essences like dandelion seeds, without the fear of being overheard or the humiliation of self-revelation, then what separates these moments from public performance? Where is the private self? What has been bared, and what remains hidden? Earlier, I postulated that one effect of filtering sounds through a wall was an increase in their emotional charge. The wall makes all human sounds primal, and, in the dual act of separating us and keeping us in close proximity to each other, the wall, and in the broader sense the city, makes us aware of ourselves as constituents of the body of humanity. But that doesn’t imply a conduit into another’s secrets, another’s essence, except insofar as it is a shared human essence, as much a part of the listener as of the subject. The weight of this revelation falls (again) on the listener, who (again) takes his place at center stage: such sounds are the substrate on which he constructs and performs his own fantasies, his own meanings, according to his own desires. So it happened with the political activist and the stalker: because I couldn’t hope to discern the meaning of that gasp, it became my own. The wall is a blank page upon which the stories of the city are written—written by the listener on the other side of the wall.

*

I have no desire to perform.N I close the bedroom door and the back windows on sweltering days, close the blinds, turn my bedroom into a perfect sounding-box for the audience of the city, my stern parent-substitutes shoving me out among the footlights. That the walls are mirrors, that the audience only sees itself—this is little consolation, though it does help me to forget that I am performing. It is folly to believe that the simple fact of my being “the listener” removes me from the sonic fingerprint of this building. Besides, my absence would only more fully reveal me. My anonymity, my un-observability—my camouflage—depend upon my doing the exact same thing everyone else does, riding along the same sonic pathway as the rest of the city. I, too, shower and shit and fry food and laugh and fuck and listen to and play music and type and slide my chair in and out. But maybe I slide my chair more frequently than the people who live in the apartments around mine. Maybe my laughter is higher and more maniacal than theirs. My fucking might be quieter, or louder, or longer, or shorter, and I might shit thrice on Sundays and only once before work. There must be a hundred such tics that give my own sonic profile its singular curve.

In the morning, the kettle and the coffee grinder: forty-five shakes, nineteen less since we started using the French press, which takes a coarser grind: from eight sets of eight shakes to five sets of eight plus five at the end. The tap, tap, tap on the bottom of the grinder when I turn it over to dump the milled coffee into the lid. The electronic kettle doesn’t whistle, though the clack of the switch turning off is pretty well audible throughout the apartment, and, I imagine, beyond. Same with the switch on the toaster. The chink of spoons and knives on glassware and porcelain, the sugarbowl. Chairs sliding in and out. Knives scraping butter onto toast. The refrigerator door. The oven door, maybe: a metallic yawn, Godzilla-like. A blob of dough beaten against the counter if I’m making bread (weekends, usually). Footsteps, hushed, because we don’t wear shoes. The wheels of the office chair—anything rolling sounds like a bowling ball to the people in the apartment downstairs. The keyboard of the computer, though I’ve only ever heard them in libraries and offices. (Scratch the keyboard.) Years ago, in Queens, I used to work on a manual typewriter. I always wondered how it sounded to the family below.

Anyway, voices. The toilet. The sink. The diligence of toothbrushes. From nine until ten, “Democracy Now” on WBAI. After, maybe “Morning Classical” and “Out to Lunch” on WKCR. No commercials. Never any jingles in our place. One day we turned off the radio and could still hear “Democracy Now,” unmistakably Amy Goodman’s voice. (This probably happens all the time if you listen to a popular music station, like Hot 97 or La Nueva Mega.) It was coming through the wall. We used the alarm issue as an excuse to invite the activist to dinner. By and large, though, the radio and TV stations I hear through the walls and ceiling tell me very little about my neighbors’ quirks and proclivities.§§ Music collections are somewhat more revealing: Downstairs, for example, they listen to Lightning Bolt and other hyper-new and arty stuff that exhausts itself moments after being produced, like elementary particles in accelerators. I learn infinitely more from my neighbors’ occasional artistic squirks and chortles than from the brand identity of the music Clear Channel has focus-grouped them into. You would expect the punk rocker to be the most musically obnoxious element in the building. But the most I ever hear from him is the James Bondish twanging of an electric guitar played without amplification. And this, perhaps, tells me more about him than if he played loud, raucous guitar in the apartment, like punk rockers are supposed to. One of the women upstairs, or maybe one of their boyfriends, had an amp, and strummed a guitar for five or ten minutes every night around midnight, bar chords with a little bit of reverb and no distortion, really digging in, like a folksinger with a borrowed Strat. And sometimes, also right around midnight, we will hear a flanged-out noise—exactly the 1950s Hollywood noise signifying flying saucer. We have never been able to pinpoint the source of this sound, though we believe it comes from the Lightning-Bolters downstairs.

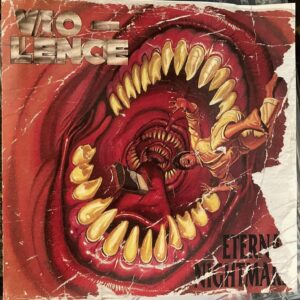

Let it be known that I am the most musically obnoxious element in this building. I play the guitar, for two hours if I can spare it, classical and flamenco, or mock-flamenco, since I play flamenco like someone imitating the sounds of a language he doesn’t speak. The political activist says she can hear me, she sometimes wakes up to the guitar, though not because of it, she says. I don’t mean her to. I play in the middle of the apartment on weekdays, in the middle of the day, when people are most likely to be working. I know the recluse hears me, too, he came to my door once on a pretext and commented on it. Their bird hears me, too—did I mention the old Italian couple has a bird?—and I’m convinced it starts singing when I play, because that’s the only time I ever hear it. Even the stalker said he could hear me through the wall. He played too, majored in music in college, I can’t remember where, someplace upstate. I never heard him play. Thin, thin walls.

The activist has also told me that, sometimes, in the middle of a piece, she hears me cough up a wad of phlegm. Now that’s something you wouldn’t hear in most live performances. Imagine living next door to Thelonious Monk, say, and hearing him cough up a wad of phlegm in the middle of “Straight, No Chaser.” Imagine hearing him lose his temper. Imagine hearing him improvising alone in his apartment; imagine what the first doodles the antic melodies his songs grew out of sounded like. Imagine him stumbling into uncharted rhythmic and harmonic alleyways, alleys only he, and now you, know exist. Imagine Monk practicing. (Would he sound just like he does live?)

It always seemed a bit unfair to me, in the artistic juggernaut that is New York, that none of us lives with, or next door to, or down the hall from, or even in the same building as, a young Thelonious Monk, or a young Tito Puente. Maybe they’re busking on subway platforms … only there they belong to everybody. Half their genius lies in our discovering them. No: we live across from a ten-year-old whose parents flog him into wanking out scales on the trumpet,*** and guitarists who haven’t yet learned that watershed fourth chord. The city is overrun by artistic hopefuls and hopelesses; like rats, we grow fat and multiply in the working-class neighborhoods of the boroughs. There must be one among us pioneers, blazing the borough trails for other white people, who will stand out, rise above. (That I am one among so many helps ensure my anonymity.) Where’s our reward for being too poor or too desperate for Manhattan, for being traitors to our race and class, for having boarded steamboats up the Gowanus canal? Exposed brick? Dishwashers? Who could be inspired by a dishwasher? One, two stops closer to Manhattan, artists have started nesting like pigeons in the abandoned factories, in the detritus of the globalizing economy, in the emptied pockets of the Superfunds. They live on clouds of silver nitrate, bathe in pools of lead, play kickball in the brownfields, while their friends surf the pissing foam of the tech boom, picking through the trash for the next million-dollar startup. Just as we’re too rich for Bushwick but too poor for Manhattan, so we’re too hip for Sunset Park but too bourgeois for Williamsburg. Like virtuous pagans, we inhabit this between-place, floating at the borders of communities without ever touching down. The punk rocker and the political activist are two paving-stones in our bridge to bohemia; I know a third in Williamsburg, a programmer. They know brilliant slide guitarists, Juilliard-trained violinists who improvise on subway platforms, downtown musicians in mid-eviction who steal their books from the dollar carts outside the Strand, anarchists who carve their names into the bones of heavy machinery. So we befriend them. We’ll settle for a degree or two of separation if it means not having to get our hands dirty. Swaddled in exposed brick (it speaks “wall” more powerfully than any other material) and hardwood floors and the hum of new appliances, we can just barely hear the pain, just enough to know it’s there, and to magnify it. The wall. It does everything for us, to us. On the other side lives the next great artist, soaking up all manner of tragedy and turning it into poetry. But who’s to say it’s not your tragedy, the tragedy of your sad life of listening, that inspires him? Or that, by listening to him, it isn’t you who will cast the beauty and terror of his life in bronze? Through the wall, the tragedies of proximate lives are given form: the wall becomes the screen through which the artist gives form to a world in which he would otherwise lose himself. And this is so important: it may be his life, but it will carry your name on it, just like his work will carry yours. A city of people who spend all day listening to one another: what on earth will they write about, paint about, sing about, if not you?

This artist, he looks like you. Like you, he’s come here to touch the soul of the city. He’s busy honing his nostalgia for that sense of neighborhood he never experienced, but knows must have existed, and must still exist, must be around here somewhere, if he just looks hard enough. (Princess! Princess!) It grows dearer and dearer in that corporate theme park still called Manhattan, soon to be branded (an island, a sports stadium, merely a difference of scale), and in its borderlands at the edges of the boroughs, where the mouse-eared monorails whisk you off to Fantasyland. He’s fled all this, the most appropriate reflection of his class, his identity. But in his conscious seeking—in all his acts of renunciation—he has already commodified his experience. Brands are the true flags of his country, whether he rejects them or wraps himself in them. At base, he still believes he can buy cheaply in the boroughs what he can’t afford in Manhattan. Because Manhattan runs on the energy provided by a collective nostalgia for its myths. And nostalgia is the easiest emotion to market, even more when it was learned through a previous generation’s collective self-representation. But he (this artist) has the privilege of losing sight of such distinctions. And he can’t understand why these people don’t feel his righteous anger, why they spend their Sundays sleepwalking down Knickerbocker from 99 cent store to 99 cent store, each with its sharp little plastic knob where it’s been twisted off from the moulding. Why they hunch their shoulders and pull up their hoods and let themselves be walked on. Anyway, they don’t speak to him. His building, a converted factory or gut-renovated walk-up, has no stoop. He’s younger, less self-conscious, less neurotic than you, but because of these things he feels his displacement all the more keenly. He’s eager to throw himself in, to swim in the body of the city, to feel whole by becoming part of it. But immediately he tries, a wall goes up. He’ll reach his hand (he says) into the cacophony of ice cream trucks and alarms and sirens and table-saws, hammers, hawkers, pushers, roosters, cats, dogs, outbursts sacred and profane. He’ll make (he says) something beautiful out of it, something that speaks the city. But he wounds himself trying—that wall again—and as he draws his hand back, the wound fixes all his attention.

Water your neuroses, Freud said. Let them grow. Fine, except it’s become our only model for artistic creation. What about those artists who walk through walls? A simple act of faith.

When we first moved in, the front half of the first floor of our building was occupied by a salsa dance studio. Our living room and office were right above it. They ran classes from five to nine on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday evenings, and then on Saturday and Sunday afternoons. Every lesson would begin with just the conga and clave. The teacher would count, sometimes in Spanish, sometimes in English (SE-ven eight). Then, the sound of her voice together with ten or fifteen pairs of shoes imperfectly synchronized, a riddle of claps to accent a beat or two. Then, together with the music, the bass buzzing the floor and windows, stampeding feet and hands, horns, joined by the sonero’s voice. Like with the ice cream truck melodies, it was impossible not to memorize these songs, the bass lines in particular—I can still sing a decent salsa bass line—but also the breaks, the melodies, the refrains. They danced the same three or four songs over and over, three times a week for a year and a half. The first class was kids, all girls, ten- or twelve-year-olds. At seven, teenagers, a smaller class, almost all girls, the few boys very pituco. If we came home in the middle of the first class, we’d see parents milling in the light of the doorway, watching, waiting to walk their kids home, and always a few random people from the neighborhood holding shopping bags.

On Tuesday and Thursday evenings they gave karate classes instead, and parents and neighbors would again gather to walk their kids home, all sons this time. The instructor, male, would count with them. Compared to the salsa, everything was so square. Ten times, everything ten, counted out in Japanese, each number punctuated by a pre-pubescent kia! … the flutter of gee-sleeves? No, I must have imagined this, it couldn’t possibly carry through the floor. Ten is the number of diligent repetition, each number valued equally. But eight is a measure; when syncopated (SE-ven-eight), five might weigh twice as much as four. The kids didn’t wear shoes, so there was no stampede, just the sound of the studio creaking like a boat while the boys hopped from side to side on the balls of their feet. At the end of class they would repeat something along with their instructor, their voices low. I could see them: the kids all kneel in rows, their hands palms-down on their thighs. I remembered the roughness of the mat against the balls of my feet. I remembered counting to ten in Japanese (I can still make it to seven), thrusting my hand or foot against an imaginary opponent. I remembered the mat was coffee-colored in places from old blood, and there were mirrors on one wall, too. I remembered the smell, and wondered if the dance studio smelled that way on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

To be honest, we were relieved if we came home to find the studio lights off and classes cancelled for the evening. But even so, and for all the occasional annoyances (like the half-hour before classes started, when the teens would turn up the hip-hop way loud)—or maybe because of them—it gave us, this odd settlement of white people, a foundation, a sense of belonging, of being rooted in this neighborhood where, every time I stepped outside, I felt like an intruder. The bass came up through the floor, yes; but more important, it drove roots down. Sometimes, like the stereos in the roving cars, the bass found the note that made our whole building quake, took hold of it and shook it like a sapling, while someone waited, I imagine, to see how many of us would fall out. But for a brief moment, all of us in the building, including the dancers, especially the dancers, hung together, plump, black, whole notes, like olives ready to drop. I imagine this even though we were the ones living directly above the studio, catching the brunt of the bass. I needed to imagine that it brought the place we were living home to us; like, if they could just turn up the bass a little louder, and the building could vibrate just a little bit harder, we would all jump out of our skins.G